Suburban Development

Overview

This section, and the Demographics page, are perhaps the most important analysis in understanding the profound changes West Windsor has experienced since the 1980s. The municipality has undergone a dramatic evolution, from a primarily white, christian, rural, sleepy township of a few thousand people to a diverse suburban community of nearly 30,000, boasting a multiplicity of racial, religious, and cultural identities.

Before the 1920s, West Windsor was completely rural. The densest agglomeration of commercial and residential development manifested at the small village clusters that dotted the township. Even these, however, were tiny specks within a much larger landscape, serving as cultural hubs for the enormous stretches of farmland - thousands upon thousands of acres - that surrounded them. Moreover, although the Camden & Amboy train line, installed in 1839 along the Delaware & Raritan Canal and relocated in 1865 to its present location, brought much economic opportunity for West Windsor, the township never surpassed 2,500 residents throughout the first 150 years of its existence.

Starting in the 1920s, this municipal identity began to transform. The development of Berrien City between 1924-1929 (albeit itself an offshoot of the older, smaller, "Berrien Heights" which was founded in 1916) and the growth of a residential community in Penns Neck (along Mather and Varsity Avenues, Fisher Place, and Washington Road) hearkened in the first era of suburban growth. The change was a small one, only , but mimicked a larger national trend of growth and relative prosperity in the "Roaring Twenties."

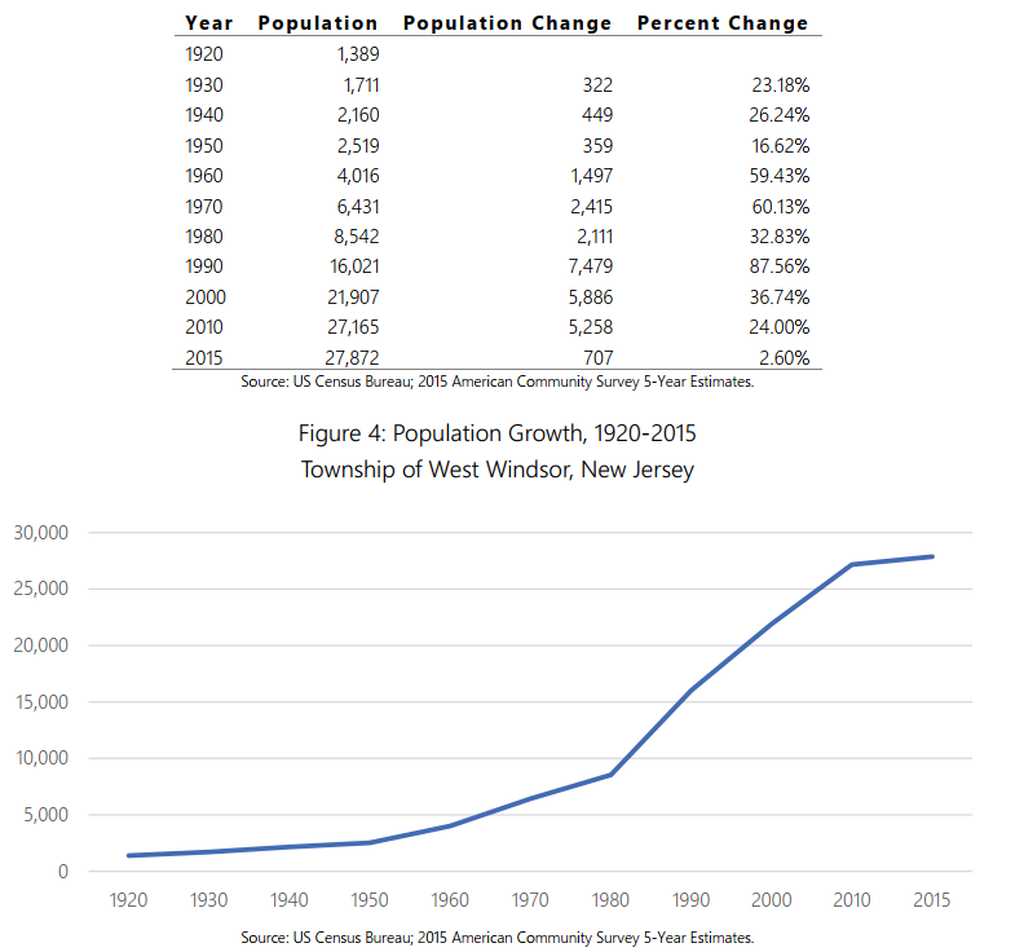

Notably, West Windsor's population growth slowed between 1940 and 1950: from 26.24% in the decade prior to 16.62%. Perhaps a combination of World War II and lingering effects from the depression contributed to this decline, pictured in the table below (taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan):

This section, and the Demographics page, are perhaps the most important analysis in understanding the profound changes West Windsor has experienced since the 1980s. The municipality has undergone a dramatic evolution, from a primarily white, christian, rural, sleepy township of a few thousand people to a diverse suburban community of nearly 30,000, boasting a multiplicity of racial, religious, and cultural identities.

Before the 1920s, West Windsor was completely rural. The densest agglomeration of commercial and residential development manifested at the small village clusters that dotted the township. Even these, however, were tiny specks within a much larger landscape, serving as cultural hubs for the enormous stretches of farmland - thousands upon thousands of acres - that surrounded them. Moreover, although the Camden & Amboy train line, installed in 1839 along the Delaware & Raritan Canal and relocated in 1865 to its present location, brought much economic opportunity for West Windsor, the township never surpassed 2,500 residents throughout the first 150 years of its existence.

Starting in the 1920s, this municipal identity began to transform. The development of Berrien City between 1924-1929 (albeit itself an offshoot of the older, smaller, "Berrien Heights" which was founded in 1916) and the growth of a residential community in Penns Neck (along Mather and Varsity Avenues, Fisher Place, and Washington Road) hearkened in the first era of suburban growth. The change was a small one, only , but mimicked a larger national trend of growth and relative prosperity in the "Roaring Twenties."

Notably, West Windsor's population growth slowed between 1940 and 1950: from 26.24% in the decade prior to 16.62%. Perhaps a combination of World War II and lingering effects from the depression contributed to this decline, pictured in the table below (taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan):

In 1958, the township's first substantial suburban housing development - Colonial Park - prompted a new era of growth. A number of developments - from Glen Acres (one of the state's first deliberately integrated neighborhoods by design, constructed in 1958) to Windsor Estates (consisting of 16 houses running from Princeton-Hightstown Road along Windsor Drive and constructed in 1958-59 by Boyce Harrison) to Piedmont Drive (18 houses off of North Mill Road built in 1958-59 by Werner-Ziff - a residential development company) were developed concurrently, but Colonial Park, at 125 houses, represented a substantial change in the scale of the township's residential projects.

Bordered by High School South to the north, Penn Lyle Road to the west, and Princeton Ivy to the east, this housing development was constructed by Werner-Ziff on a farm once owned by the D. K. Vorhees family.

Doubtless, while its owners inevitably recognized the development's location within a larger agrarian setting, its proximity to Princeton and Brunswick Pike took precedence in advertisements. Proclaimed a flyer:

Bordered by High School South to the north, Penn Lyle Road to the west, and Princeton Ivy to the east, this housing development was constructed by Werner-Ziff on a farm once owned by the D. K. Vorhees family.

Doubtless, while its owners inevitably recognized the development's location within a larger agrarian setting, its proximity to Princeton and Brunswick Pike took precedence in advertisements. Proclaimed a flyer:

"Princeton is considered by many people to be the finest residential area in New Jersey... and for that matter, one of the finest anywhere. It is enriched by the cultural traditions of Princeton University. It has the attention of scholars and travelers throughout the world. Yet, for all its fame, Princeton has maintained a demeanor of small town refinement. Gracious homes, wide streets, uncrowded living. You enjoy a full life in this beautiful community. And you have every local and commuting convenience. The Modern Princeton Shopping Center, public schools and houses of worship are only minutes away. The Princeton railroad station is within five minutes. The New Jersey Turnpike and U.S. Route 1 are within easy reach."

Notice how West Windsor is not once mentioned! As the township grew, its residential develops began to brand themselves with more recognizable monikers, often adopting "Princeton" or "Grovers Mill" into their names. Similarly, the streets of Princeton Colonial Park were named after recognizable icons: University and Nassau Place after Princeton, Ziff lane after the original developer, Colonial Avenue after one of the house styles, Canoe Brook Drive after a local creek, and Quaker Road after some of the area's original European settlers and landholders. Only Jeffery Lane remains a mystery; it may have been the name of someone related to the developers.

Eventually, Werner-Ziff, who underpriced the first houses (mainly split-level designs), lost money on the venture, whereupon it was taken over by Hilton Realty. Newer, bigger houses were constructed, whereupon buyers could choose from three different styles of houses: the Lafayette Ranch Home, the Hamilton, Split Level and the Washington 2-story Colonial. The model homes were located at 54 Penn Lyle Road (ranch-style), 56 Penn Lyle Road (split level), and 58 Penn Lyle Road (colonial), Each home had slight variations to distinguish them from their neighbors. A colorful pamphlet depicting this variety of architecture can be found here!

According to questionnaires filled out by residents of Princeton Colonial Park, most first-time buyers were employed in local organizations, such as the RCA labs, FMC, and Princeton Plasma Lab, and New Jersey Bell. In a story familiar to West Windsor residents today, many also routinely commuted to New York and Philadelphia for work.

Most home buyers had school-age children, contributing to the growth of the local school system (Maurice Hawk was built in the mid-1960s and the West Windsor-Plainsboro Board of Education was incorporated in 1969). In the 1990s, many of these residents were interviewed by the Historical Society of West Windsor in 1996. Their memories of the development can be read below:

According to questionnaires filled out by residents of Princeton Colonial Park, most first-time buyers were employed in local organizations, such as the RCA labs, FMC, and Princeton Plasma Lab, and New Jersey Bell. In a story familiar to West Windsor residents today, many also routinely commuted to New York and Philadelphia for work.

Most home buyers had school-age children, contributing to the growth of the local school system (Maurice Hawk was built in the mid-1960s and the West Windsor-Plainsboro Board of Education was incorporated in 1969). In the 1990s, many of these residents were interviewed by the Historical Society of West Windsor in 1996. Their memories of the development can be read below:

Following Colonial Park's establishment was a blossoming of large residential developments. Between the late 1950s and the mid-1970s, roughly a dozen large, mid-century communities, and several thousand new residents, called West Windsor home. Click on the map below to compare West Windsor in 1959 vs today.

Click on map to view 1975 WW!

Click on map to view 1975 WW!

Part of the reason for so much growth was the introduction of the sewer system to the township; previously, outhouses, septic tanks, rivers, and fields provided disposal of human waste. However, sewers, and every modern plumbing convenience associated with it, proved enticing to developers and tentative residents alike.

While these aforementioned developments significantly expanded the township's population - from 40,16 in 1960 to 6,432 in 1970 - and partially resulted in the creation of Plainsboro and West Windsor's ever-expanding school system in 1969 - it wasn't until the 1980s that growth began to skyrocket. In fact, in 1960, the township's topography was still 65 percent agrarian - doubtless an unrecognizable landscape today!

Between 1980 and 1990, the township experienced its most significant population "boom" - from 8,542 to 16,021 residents. This resulted in the construction of numerous developments (too many to list here) throughout the municipality. Slowly but surely, West Windsor's identity was morphing into something less and less similar to the great bucolic expanses of the Midwest, and more and more akin to a suburbia.

With this growth came significant infrastructural change. Roads were widened, new sewers were installed, schools were constructed, and bridges built. Of particular note were the construction of overpasses at the intersection of the Northeast Corridor railroad line and Clarksville, Alexander, Washington, and Meadow Roads in the 1990s. Previously, these four junctions had been at-grade crossings, as rail and car travel was less busy during the first three quarters of the century.

Concurrently, the municipality began to recognize the need to stave off too much growth and provide services for its existing residents. As a result, the integration of an "open space" element into its master plan - i.e. a scheme to preserve the wildlife, agricultural identity, and recreational opportunities of West Windsor - began to take shape. Read more about this decades-long municipal venture here!

While these aforementioned developments significantly expanded the township's population - from 40,16 in 1960 to 6,432 in 1970 - and partially resulted in the creation of Plainsboro and West Windsor's ever-expanding school system in 1969 - it wasn't until the 1980s that growth began to skyrocket. In fact, in 1960, the township's topography was still 65 percent agrarian - doubtless an unrecognizable landscape today!

Between 1980 and 1990, the township experienced its most significant population "boom" - from 8,542 to 16,021 residents. This resulted in the construction of numerous developments (too many to list here) throughout the municipality. Slowly but surely, West Windsor's identity was morphing into something less and less similar to the great bucolic expanses of the Midwest, and more and more akin to a suburbia.

With this growth came significant infrastructural change. Roads were widened, new sewers were installed, schools were constructed, and bridges built. Of particular note were the construction of overpasses at the intersection of the Northeast Corridor railroad line and Clarksville, Alexander, Washington, and Meadow Roads in the 1990s. Previously, these four junctions had been at-grade crossings, as rail and car travel was less busy during the first three quarters of the century.

Concurrently, the municipality began to recognize the need to stave off too much growth and provide services for its existing residents. As a result, the integration of an "open space" element into its master plan - i.e. a scheme to preserve the wildlife, agricultural identity, and recreational opportunities of West Windsor - began to take shape. Read more about this decades-long municipal venture here!

As of 2019, West Windsor is a municipality of almost 30,000 residents. Growth has slowed down since the 1980s - from nearly 90% between 1980 and 1990 to around 25% from 2000-2010 (returning to its 1920-1930 level) as the township's residentially-zoned areas become saturated. Nevertheless, the township's agrarian dominance, marked by dirt roads cutting through vast fields, is long-gone, having given way to avenues, streets, boulevards, and drives. Some of the township's most rural areas - notably along Clarksville Road near its intersection with Quakerbridge Road and along Washington Road west of Brunswick Pike - are threatened by further development, a product of even more growth within the nation's densest state.

All of this is not to say that West Windsor is changing for the worse; rather, merely that is it changing. It is important to note that a historical analysis of West Windsor would be remiss if it were not to examine the transformation of the township over the past half century - from a sleepy, bucolic community to a bustling suburbia. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in one of West Windsor's oldest villages - Dutch Neck:

All of this is not to say that West Windsor is changing for the worse; rather, merely that is it changing. It is important to note that a historical analysis of West Windsor would be remiss if it were not to examine the transformation of the township over the past half century - from a sleepy, bucolic community to a bustling suburbia. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in one of West Windsor's oldest villages - Dutch Neck: