Natural Resources

Woods near Quakerbridge and Village Roads

Woods near Quakerbridge and Village Roads

Overview

West Windsor occupies the westernmost strip of the Atlantic inner coastal plain. To the west are the hills of Princeton, overlooking Lake Carnegie. To the north is the Millstone River, which flows north towards the Raritan River. To the south is the Assunpink, which flows westward into the Delaware. And to the east are the plains of East Windsor.

In order to understand the history of West Windsor, one must analyze its topography, wildlife, and natural habitats. The resources that the area's inhabitants - from the earliest settlers to the newest residents - used and use for food, transportation, construction, and a myriad of other purposes cannot simply be glossed over. Thus, this page will examine a few frames with which to view West Windsor's uniquely opportune environment:

West Windsor occupies the westernmost strip of the Atlantic inner coastal plain. To the west are the hills of Princeton, overlooking Lake Carnegie. To the north is the Millstone River, which flows north towards the Raritan River. To the south is the Assunpink, which flows westward into the Delaware. And to the east are the plains of East Windsor.

In order to understand the history of West Windsor, one must analyze its topography, wildlife, and natural habitats. The resources that the area's inhabitants - from the earliest settlers to the newest residents - used and use for food, transportation, construction, and a myriad of other purposes cannot simply be glossed over. Thus, this page will examine a few frames with which to view West Windsor's uniquely opportune environment:

Hiking trail behind the RCA property

Hiking trail behind the RCA property

Topographic Slope

Unlike Princeton, West Windsor's landscape displays little elevation variation - only from roughly 60 to 100 feet above sea level. Some of the largest elevation changes can be found along Rabbit Hill Road (between Bear Brook and Princeton-Hightstown Road), along the Millstone River behind the RCA property in Penns Neck, and in Princeton Basin. However, beyond these small hills, much of West Windsor is extremely flat. The vast majority of the landscape is on less than a 5% grade, offering many opportunities for development of all categories (commercial, residential, industrial, etc).

However, this flat terrain is a double-edged sword. During periods of heavy rainfall, the lack of significant slopes often proves troublesome, as water is slow to drain - killing crops, damming up roads, infiltrating basements, and providing breeding grounds for mosquitoes and other insects.

Thus, early settlers faced a mixed blessing. During periods of relatively little rainfall, the soil provided vast areas of arable land rich in nutrients and rarely prone to drought. However, during downpours, an influx of water could threaten crops and make transportation difficult.

Below is a contoured map, taken from the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory, showing both elevation above sea level and the slope of soil throughout West Windsor:

Unlike Princeton, West Windsor's landscape displays little elevation variation - only from roughly 60 to 100 feet above sea level. Some of the largest elevation changes can be found along Rabbit Hill Road (between Bear Brook and Princeton-Hightstown Road), along the Millstone River behind the RCA property in Penns Neck, and in Princeton Basin. However, beyond these small hills, much of West Windsor is extremely flat. The vast majority of the landscape is on less than a 5% grade, offering many opportunities for development of all categories (commercial, residential, industrial, etc).

However, this flat terrain is a double-edged sword. During periods of heavy rainfall, the lack of significant slopes often proves troublesome, as water is slow to drain - killing crops, damming up roads, infiltrating basements, and providing breeding grounds for mosquitoes and other insects.

Thus, early settlers faced a mixed blessing. During periods of relatively little rainfall, the soil provided vast areas of arable land rich in nutrients and rarely prone to drought. However, during downpours, an influx of water could threaten crops and make transportation difficult.

Below is a contoured map, taken from the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory, showing both elevation above sea level and the slope of soil throughout West Windsor:

Soil Quality and Agriculture

Like much of the rest of New Jersey, West Windsor boasts fertile soil that has made it a home to profitable farms for centuries. In accordance with the New Jersey State Agricultural Land Value Assessment's classification of prime soils into "very productive farmland" and "good farmland," West Windsor contains only these two types of soil - the foundation upon which its farms profited.

As a result, West Windsor's agricultural sector dominated its identity until as recently as the last quarter of the 20th century. Although it has given way to a suburban identity, echoes of its bucolic past are dispersed throughout the township.

Unfortunately, the characteristics that distinguish good agrarian land - namely fertility, gentle slope, depth, and drainage - also make it prime land for urban and suburban development. So, too, do slope, erosion hazard, drainage, depth to bedrock, depth to seasonably high water table, runoff potential, and suitability for septic drainage field - all evaluated in the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory as constraints on suburban development. The two maps below show a high correlation between farmland and suburban suitability:

Like much of the rest of New Jersey, West Windsor boasts fertile soil that has made it a home to profitable farms for centuries. In accordance with the New Jersey State Agricultural Land Value Assessment's classification of prime soils into "very productive farmland" and "good farmland," West Windsor contains only these two types of soil - the foundation upon which its farms profited.

As a result, West Windsor's agricultural sector dominated its identity until as recently as the last quarter of the 20th century. Although it has given way to a suburban identity, echoes of its bucolic past are dispersed throughout the township.

Unfortunately, the characteristics that distinguish good agrarian land - namely fertility, gentle slope, depth, and drainage - also make it prime land for urban and suburban development. So, too, do slope, erosion hazard, drainage, depth to bedrock, depth to seasonably high water table, runoff potential, and suitability for septic drainage field - all evaluated in the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory as constraints on suburban development. The two maps below show a high correlation between farmland and suburban suitability:

As suburban development takes over a township, escalating land prices and taxes, loss of support services, stricter environmental regulations, and urban spillover all combine as pressures on a farmer, forcing them to sell farmland for development. In addition, fertile soil is a non-renewable resource, irrecoverable and forever transformed once development has taken over. Prime soils - whether agrarian or forested - play a crucial role in aquifer recharge and wildlife feeding grounds, and, arguably, provide a psychological benefit associated with wildlife and open space.

Thus, according to the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory, the preservation of agricultural land is a crucial priority for West Windsor. Not only does it retain the agrarian identity of the township's past and prevent a too-rapid surge in population growth that the township's infrastructure cannot handle; it also helps the locality be self-sufficient and its wildlife habitats flourish.

Thus, according to the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory, the preservation of agricultural land is a crucial priority for West Windsor. Not only does it retain the agrarian identity of the township's past and prevent a too-rapid surge in population growth that the township's infrastructure cannot handle; it also helps the locality be self-sufficient and its wildlife habitats flourish.

Vegetation and Wildlife Habitats

Although it may be easy to miss, a significant diversity of wildlife habitats, and the flora and fauna contained therein, exists in West Windsor. As a result, and in contrast with ecosystems with only a few dominant species, West Windsor's ecosystem is resilient - to our benefit.

According to the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory, wide swaths and a variety of of plant life species impart a myriad of benefits onto their localities. Verdant areas with rich root structures help slow runoff and erosion, making sure that our topography remains maintainable. Leafy and aquatic plants help filter out air and water pollutants, reducing health risks. Forested areas act as natural wind barriers, carbon dioxide filters, and heat retainers, helping to moderate the local climate. Vegetation acts as a food source for both ourselves and the animals that surround us. Finally, plant and animal life has been shown to have a positive psychological effect on the people who exist near to it.

Maintaining the equilibrium of our ecosystem is vital to ensure West Windsor's, and its residents', health and well-being. In order to ensure this outcome, however, we must recognize the different biomes that exist within the township:

Although it may be easy to miss, a significant diversity of wildlife habitats, and the flora and fauna contained therein, exists in West Windsor. As a result, and in contrast with ecosystems with only a few dominant species, West Windsor's ecosystem is resilient - to our benefit.

According to the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory, wide swaths and a variety of of plant life species impart a myriad of benefits onto their localities. Verdant areas with rich root structures help slow runoff and erosion, making sure that our topography remains maintainable. Leafy and aquatic plants help filter out air and water pollutants, reducing health risks. Forested areas act as natural wind barriers, carbon dioxide filters, and heat retainers, helping to moderate the local climate. Vegetation acts as a food source for both ourselves and the animals that surround us. Finally, plant and animal life has been shown to have a positive psychological effect on the people who exist near to it.

Maintaining the equilibrium of our ecosystem is vital to ensure West Windsor's, and its residents', health and well-being. In order to ensure this outcome, however, we must recognize the different biomes that exist within the township:

- Herbaceous Freshwater Marshes support a diversity of flora and fauna. They filter suspended solids and support a wide swath of plants, improving water quality as a result. Their spongy organic base - "peat" - helps mitigate extreme floods and recharge groundwater basins.

- Lowland Shrubs provide dense cover for wildlife on flood plains

- Lowland Forests are comprised of two main types within West Windsor - red maple and sweetgum. These two environments house the greatest number of wildlife species in the township - the majority of which are the bird species that we enjoy spotting in our backyards. Trees provide cover, food, shade, and safety for smaller species and reduce heating and cooling needs for buildings. Their roots also contribute significantly to erosion control and flood mitigation.

- Upland Forests are located on well-drained soils, providing a similar benefits to lowland forests. There are two main types in West Windsor: oak and mixed species.

- Open Land consists of cultivated and fallow fields. A number of once-farmed fields in the township have long been abandoned, and are in a transitional stage before they become forested. Fields are important wildlife habitats for many rodents and birds and provide feeding grounds for a variety of forest dwellers.

- Sod Farms are a man-made category, consisting of fewer wildlife species than the previously listed environments.

- Suburban land is even less populated, due to the lack of underbrush and proximity to humans.

- Bare land is the last category, consisting of paved and cleared surfaces. No vegetation beyond weeds growing through cracks, and no wildlife beyond the occasional insect, live in these areas.

Now, where exactly are these different wildlife areas located? In 1976, the township developed its extensive "Greenbelt" plan - an interconnected system of woodlands, wetlands, and open space areas forming a continuous corridor throughout the municipality. This plan helps ensure the preservation of the various wildlife habitats listed above, and their aforementioned benefits. While most of the Greenbelt is composed of natural woodlands and wetlands, some farmland acts as overland connections, linking different parts of the scheme. While much of these connections may appear to be abandoned land, they are actually in the aforementioned transitional stages from field to forest, inviting a succession of flora and fauna as they mature. The below map was taken from the township's master plan:

The Millstone River behind the RCA property

The Millstone River behind the RCA property

Rivers, Streams, and Canals

The rivers, creeks, and streams in West Windsor have a storied history. They were likely first used for transportation and fishing by the area's first settlers, including the Lenni Lenape. When Europeans started arriving in the mid-1600s, these waterways likewise served as a convenient method of transportation, as roads and footpaths were often dilapidated (see the "Footpaths and Roads" web page for more information). Additionally, several mills - from Elison Carson's grist mill in Edinburg to Jacob Scudder's mill in Aqueduct - owed their existence to the perpetual motion of water that traversed the township.

The 1849 and 1875 maps of West Windsor show the same arteries that we see today; albeit slightly shifted, as streams tend to move over time. West Windsor's historic boundaries are largely informed by these streams. The Stony Brook served as West Windsor's western boundary during much of the 1800s. Even longer lasting was the Millstone River, comprising the entirety of the township's northern boundary from its formation until today.

The major streams that have called West Windsor home for hundreds, if not thousands of years include: Assunpink Creek to the south, the Millstone River in the north, Stony Brook, Duck Pond Run, and Little Bear Brook in the west, and Big Bear Brook in the east. More minor tributaries are largely offshoots of these larger arteries and are thus given the same names as their parent waterways, except for two - Bridegroom Run, an offshoot of the Assunpink Creek in the southeast, and Canoe Brook, in the center of the township. Additionally, one other small creek - given no colloquial name today but present as a small brook that runs under North Mill Road directly south of its intersection with Clarksville Road - shows up on an 1805 map of Grovers Mill as "Turner Brook."

The rivers, creeks, and streams in West Windsor have a storied history. They were likely first used for transportation and fishing by the area's first settlers, including the Lenni Lenape. When Europeans started arriving in the mid-1600s, these waterways likewise served as a convenient method of transportation, as roads and footpaths were often dilapidated (see the "Footpaths and Roads" web page for more information). Additionally, several mills - from Elison Carson's grist mill in Edinburg to Jacob Scudder's mill in Aqueduct - owed their existence to the perpetual motion of water that traversed the township.

The 1849 and 1875 maps of West Windsor show the same arteries that we see today; albeit slightly shifted, as streams tend to move over time. West Windsor's historic boundaries are largely informed by these streams. The Stony Brook served as West Windsor's western boundary during much of the 1800s. Even longer lasting was the Millstone River, comprising the entirety of the township's northern boundary from its formation until today.

The major streams that have called West Windsor home for hundreds, if not thousands of years include: Assunpink Creek to the south, the Millstone River in the north, Stony Brook, Duck Pond Run, and Little Bear Brook in the west, and Big Bear Brook in the east. More minor tributaries are largely offshoots of these larger arteries and are thus given the same names as their parent waterways, except for two - Bridegroom Run, an offshoot of the Assunpink Creek in the southeast, and Canoe Brook, in the center of the township. Additionally, one other small creek - given no colloquial name today but present as a small brook that runs under North Mill Road directly south of its intersection with Clarksville Road - shows up on an 1805 map of Grovers Mill as "Turner Brook."

Left to Right: Millstone River, D&R Canal, Lake Carnegie

Left to Right: Millstone River, D&R Canal, Lake Carnegie

Only one major waterway in West Windsor is artificial - the Delaware and Raritan (D&R) Canal, completed in 1834. For nearly a hundred years, the canal proved a boon for West Windsor, offering easy transportation of cargo - ironically including coal, which powered the train industry that would inevitably kill the canal industry. This artery resulted in the creation of two of West Windsor's villages - Port Mercer and Princeton Basin - and likely contributed greatly to the economy of two others - Penns Neck and Aqueduct.

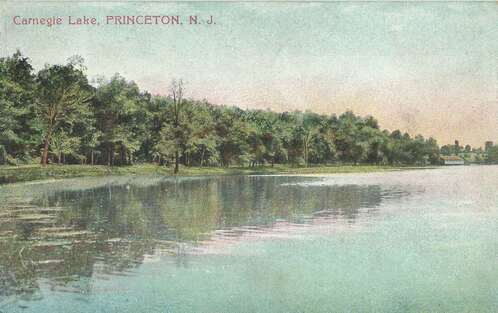

Particularly interesting is the confluence of the D&R Canal, the Millstone River, and Lake Carnegie (which itself runs over the much older Stony Brook). This intersection occurs in the historic village of Aqueduct, named after a venerable aqueduct which carries the canal past the neighboring lake and river. On the aqueduct are platforms for fishing and brilliant panoramic sunset views.

Although it has not been used for commercial transportation since the 1930s, the D&R Canal still functions as a popular recreation area for those wanting to jog or canoe, allowing people travelling down the waterway to experience echoes of a once-popular commercial artery.

Particularly interesting is the confluence of the D&R Canal, the Millstone River, and Lake Carnegie (which itself runs over the much older Stony Brook). This intersection occurs in the historic village of Aqueduct, named after a venerable aqueduct which carries the canal past the neighboring lake and river. On the aqueduct are platforms for fishing and brilliant panoramic sunset views.

Although it has not been used for commercial transportation since the 1930s, the D&R Canal still functions as a popular recreation area for those wanting to jog or canoe, allowing people travelling down the waterway to experience echoes of a once-popular commercial artery.

Postcard from 1910

Postcard from 1910

Lakes

West Windsor has no natural lakes. The three large bodies of water that residents use, primarily, for recreation are: the pond at Grovers Mill (constructed in the mid-1700s), Lake Carnegie (1905-1906), and Mercer Lake (1970s). Historically, the first reservoir was used to power a grist mill from the mid-1700s until the 1940s. The second was excavated as one of Andrew Carnegie's many public works projects, prompted by a discussion with a member of the Princeton rowing crew - who was rapidly growing annoyed at having to squeeze past barges on the Delaware & Raritan Canal - their previous avenue of travel. Although it lies outside West Windsor's boundaries, its size and proximity to the township make it suitable for this analysis. The third has only ever been used for recreation - from rowing to kayaking to fishing.

West Windsor has no natural lakes. The three large bodies of water that residents use, primarily, for recreation are: the pond at Grovers Mill (constructed in the mid-1700s), Lake Carnegie (1905-1906), and Mercer Lake (1970s). Historically, the first reservoir was used to power a grist mill from the mid-1700s until the 1940s. The second was excavated as one of Andrew Carnegie's many public works projects, prompted by a discussion with a member of the Princeton rowing crew - who was rapidly growing annoyed at having to squeeze past barges on the Delaware & Raritan Canal - their previous avenue of travel. Although it lies outside West Windsor's boundaries, its size and proximity to the township make it suitable for this analysis. The third has only ever been used for recreation - from rowing to kayaking to fishing.

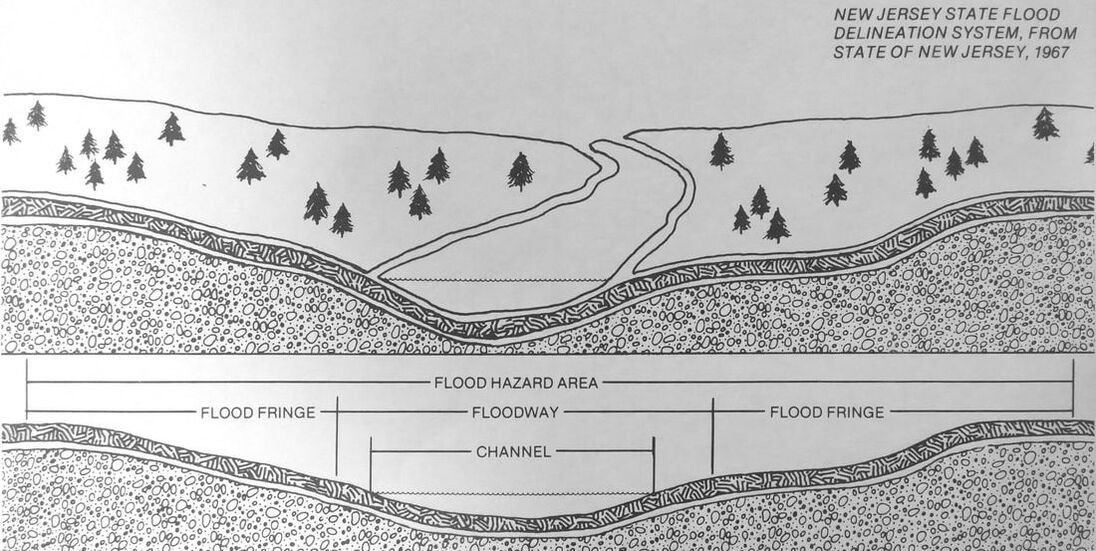

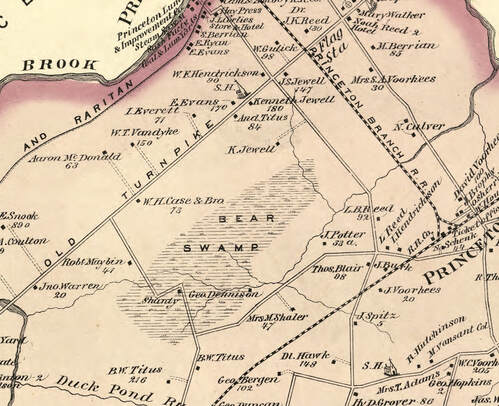

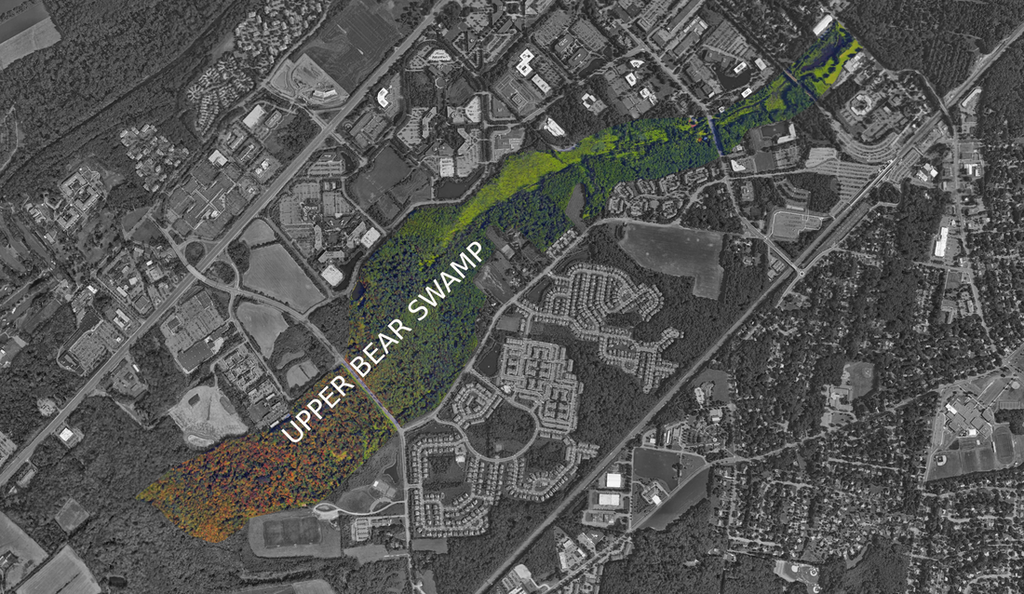

While these three categories of water topography - rivers, swamps, and lakes - provide opportunities for transportation and food - they also pose a flooding risk for the township, creating risks for our transportation and residential infrastructure and even endangering life. Six main flood basins (based on a 100-year flood boundary) exist in the township, and are shown below (map taken from the township's 1991 Natural Resource Inventory). Note the Little Bear Brook Basin, which aligns with Upper Bear Swamp.

Despite their disadvantages, these flood plains are of substantial ecological value. Sediments deposited by slow-moving waters provide lush landscapes and fertile farmland. Undeveloped flood plains are also excellent habitats for wildlife, due to the proximity to water. Overhanging vegetation offers shade and refuge for steam organisms and help maintain natural stream temperatures. It also filters out pollutants, enhancing the quality of water. This bounty of flora yields a bounty of the fauna that feeds off of it, further benefiting humans by providing serene landscapes for environmental study and natural resources.

Settlers naturally tended to avoid this area because its marshy terrain proved difficult to traverse, hard to farm on, and is a breeding ground for insects of all sorts. In fact, in contrast to the heavily-trafficked areas around it, there is still little development in Upper Bear Swamp today, due to its poorly drained soils. In 2015, local resident Dick Snedeker wrote an article about this drainage and the "water woes" of West Windsor. He pointed out that, because of the township's extremely flat topolgraphy, both Little Bear Brook and Duck Pond Run can either feed or be fed by Upper Bear Swamp, depending on the rainfall rate.

Tatamy's swamp is roughly bordered by Clarksville Road to the northwest, Penn-Lyle Road to the southeast, and Duck Pond Run to the southwest .

Tatamy, a prominent Lenni Lenape figure, was born around 1695, either in the greater Trenton area or in Holland Township in Hunterdon County. He carved out for himself a prominent role in Colonial history, serving as an interpreter and first convert for the famed missionary David Brainerd, and a diplomat who bridged the cultural divide that drove a wedge between British American and the Lenni Lenape.

After the 1727 extrajudicial arrest and execution of Weequehela, leader of Tatamy's tribe, Moses sought to appease the Europeans by adopting Christianity and learning English. He bet that by doing so, he would secure his peoples' right to existence in an age of conquest. And indeed it did - for a time. Tatamy served as an agent for the Delaware, handling all land disputed in New Jersey by 1758, in addition to his role as a cultural diplomat who conferred with the governors of both Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

As a result of his efforts, Tatamy grew in prominence. In 1737, the same year that William Penn's sons - Thomas, Richard, and John - deeded 6,500 acres of land (later known as Penns Neck) to John Covenhoven and Garret Schenck, his name began to appear on maps of what would become West Windsor, where the swamp exists today. In December of the year prior, he had been granted three hundred and fifteen acres of land by the Colony of Pennsylvania in the Lehigh Valley, near the Native American village of Welagameka, with the document of transferral indicating the Penns' "love and affection for Tatamy." Therefore, it is possible that Tatamy also owned some occupation rights to the land that is now known as Tatamy's Swamp.

Near the end of his life, the French and Indian War (1754-1763) erupted, shattering this peace. It was in 1760 that Tatamy died. He was buried in an unmarked grave on a small knoll. It is believed that this grave site is just southeast of the bend in Clarksville Road (heading towards Quakerbridge Road) before going over the railroad tracks, in the woods behind Haskel Drive.

A more extensive (and exciting!) analysis of the hunt for this swamp's historical location can be found here. Moreover, a more detailed exploration of Tatamy's life can be found on our Prominent Figures section.

In 2019, much of Tatamy's swamp has been filled in and developed. However, a remnant of the swamp can be seen surrounding Duck Pond Run, especially south of Jacob Drive to the west of North Post Road. Below is a map showing the region covering historic Tatamy's swamp and his possible burial location:

Tatamy, a prominent Lenni Lenape figure, was born around 1695, either in the greater Trenton area or in Holland Township in Hunterdon County. He carved out for himself a prominent role in Colonial history, serving as an interpreter and first convert for the famed missionary David Brainerd, and a diplomat who bridged the cultural divide that drove a wedge between British American and the Lenni Lenape.

After the 1727 extrajudicial arrest and execution of Weequehela, leader of Tatamy's tribe, Moses sought to appease the Europeans by adopting Christianity and learning English. He bet that by doing so, he would secure his peoples' right to existence in an age of conquest. And indeed it did - for a time. Tatamy served as an agent for the Delaware, handling all land disputed in New Jersey by 1758, in addition to his role as a cultural diplomat who conferred with the governors of both Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

As a result of his efforts, Tatamy grew in prominence. In 1737, the same year that William Penn's sons - Thomas, Richard, and John - deeded 6,500 acres of land (later known as Penns Neck) to John Covenhoven and Garret Schenck, his name began to appear on maps of what would become West Windsor, where the swamp exists today. In December of the year prior, he had been granted three hundred and fifteen acres of land by the Colony of Pennsylvania in the Lehigh Valley, near the Native American village of Welagameka, with the document of transferral indicating the Penns' "love and affection for Tatamy." Therefore, it is possible that Tatamy also owned some occupation rights to the land that is now known as Tatamy's Swamp.

Near the end of his life, the French and Indian War (1754-1763) erupted, shattering this peace. It was in 1760 that Tatamy died. He was buried in an unmarked grave on a small knoll. It is believed that this grave site is just southeast of the bend in Clarksville Road (heading towards Quakerbridge Road) before going over the railroad tracks, in the woods behind Haskel Drive.

A more extensive (and exciting!) analysis of the hunt for this swamp's historical location can be found here. Moreover, a more detailed exploration of Tatamy's life can be found on our Prominent Figures section.

In 2019, much of Tatamy's swamp has been filled in and developed. However, a remnant of the swamp can be seen surrounding Duck Pond Run, especially south of Jacob Drive to the west of North Post Road. Below is a map showing the region covering historic Tatamy's swamp and his possible burial location:

Suburban development throughout the 20th century has changed some of West Windsor’s topology. Once-impassable swamps are now cut through by the heavily-trafficked Northeast Corridor rail line, as well as less busy but still solid suburban streets. Housing projects cover hundreds, if not thousands, of acres of once-lush farm and woodland. Mercer County Lake and Lake Carnegie have created monumental reservoirs of water, expanding the rivers that once ran in their place - Stony Brook and Assunpink Creed, respectively.

However, the hills remain mostly the same as they were a century ago. West Windsor is still a predominately flat land, cut through by swamps to the west and scattered rivers across its surface. wildlife areas remain intact as a result of the establishment of West Windsor’s Greenbelt decades ago and efforts to preserve our agrarian landscape ensuring that our township's historic topology will remain for generations to come.

Take some time to enjoy some of West Windsor’s lush nature preserves. The Ron Roger’s Preserve along Clarksville Road, Mercer County Park, and Zaitz Park just north of the Schenck Farmstead are just three of several areas in the township offering hiking trails and recreational areas that traverse a variety of landscapes representative of West Windsor’s diverse topographical offerings.

However, the hills remain mostly the same as they were a century ago. West Windsor is still a predominately flat land, cut through by swamps to the west and scattered rivers across its surface. wildlife areas remain intact as a result of the establishment of West Windsor’s Greenbelt decades ago and efforts to preserve our agrarian landscape ensuring that our township's historic topology will remain for generations to come.

Take some time to enjoy some of West Windsor’s lush nature preserves. The Ron Roger’s Preserve along Clarksville Road, Mercer County Park, and Zaitz Park just north of the Schenck Farmstead are just three of several areas in the township offering hiking trails and recreational areas that traverse a variety of landscapes representative of West Windsor’s diverse topographical offerings.