Demographic Changes

Note: from 2021 to 2022, a group of three High School South students - Donna Gosh, Naomi Lyu, and Neeharika Suvvari - explored the demographic changes of the WW-P school system and local religious institutions. Their work was memorialized in a research paper that the Historical Society will use as a basis for future research - CLICK HERE to view it!

An interesting juxtoposition of old and new is displayed by the Muslim Center of Greater Princeton's location adjacent to the old Ayres farm!

An interesting juxtoposition of old and new is displayed by the Muslim Center of Greater Princeton's location adjacent to the old Ayres farm!

Overview

This section, and the "Suburbanization" page, are perhaps the most important analysis in understanding the profound changes West Windsor has experienced since the last quarter of the twentieth century. The municipality has undergone a dramatic evolution, from a primarily white, Christian, rural, sleepy township of a few thousand people to a diverse suburban community of nearly 30,000, boasting a multiplicity of racial, religious, and cultural identities. While it may be tempting to start studying the end of the 20th century and beyond in isolation, in order to truly comprehend the "salad bowl" (a more updated version of the "melting pot" analogy) of identities that is the township's racial, cultural, and religious composition, and its contrast with the West Windsor of centuries past, it is prudent to start at the beginning...

The indigenous population of what is now West Windsor descended from the Asiatic people who first migrated to the region thousands of years ago when the glaciers of the last ice age first started retreating. These settlers are theorized to have arrived both by raft over the Pacific Ocean and by foot, crossing the then-extant frozen land-bridge connecting present-day Russia and Alaska. Remnants of their local presence - such as tools and bone fragments - are still found throughout the coastal plains of eastern North America.

This section, and the "Suburbanization" page, are perhaps the most important analysis in understanding the profound changes West Windsor has experienced since the last quarter of the twentieth century. The municipality has undergone a dramatic evolution, from a primarily white, Christian, rural, sleepy township of a few thousand people to a diverse suburban community of nearly 30,000, boasting a multiplicity of racial, religious, and cultural identities. While it may be tempting to start studying the end of the 20th century and beyond in isolation, in order to truly comprehend the "salad bowl" (a more updated version of the "melting pot" analogy) of identities that is the township's racial, cultural, and religious composition, and its contrast with the West Windsor of centuries past, it is prudent to start at the beginning...

The indigenous population of what is now West Windsor descended from the Asiatic people who first migrated to the region thousands of years ago when the glaciers of the last ice age first started retreating. These settlers are theorized to have arrived both by raft over the Pacific Ocean and by foot, crossing the then-extant frozen land-bridge connecting present-day Russia and Alaska. Remnants of their local presence - such as tools and bone fragments - are still found throughout the coastal plains of eastern North America.

2019 Nanticoke Lenape Pow Wow. Click image for link!

2019 Nanticoke Lenape Pow Wow. Click image for link!

In 1867, Charles Conrad Abbott - a farmer who owned property south of Trenton - unearthed a series of stone implements dating to just after the glacial retreat on his farm, "Three Beeches," along the banks of the Delaware River. This discovery, concurrent with Charles Darwin's seminal "Origin of Species," caused a sensation in the United States, focused around the anthropological roots of human civilization. Since then, many more artifacts have been found throughout West Windsor, along the banks of the Assunpink Creek, Bear Brook, and Millstone River. Vessel fragments, a hearth, and various stone tools evoke the culture of a people that inhabited the continent thousands of years before the first Europeans even knew of its existence.

The Lenni Lenape are likely the descendants of these first inhabitants. This collection of several smaller tribes, each of which spoke dialects of the Algonquin language, were the first indigenous people that European settlers met in the region. Europeans dubbed this tribe the "Delaware," a name derived from English aristocrat Lord de la Warr. Although the majority of the Lenape were relocated thousands of miles away to Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Canada, a small contingent still lives in New Jersey. A further analysis of their culture and history in and around West Windsor and New Jersey is on the "Earliest Inhabitants & the Lenni Lenape" page.

The first Europeans to settle in New Jersey were Swedes, English, and the Dutch (who eventually developed such a unique culture that they became known as the "Jersey Dutch"), starting in the mid-1600s. Many of these families are still around today: the Schencks, Covenhovens, Perines, Bergens, Updikes, Vorhees, and Wyckoffs. The naming of historic village clusters such as Dutch Neck and Penns Neck still bear witness to the vernacular of this ethnic group. Even the architectural development of the region is influenced by Dutch practices, such as the assembly of the barn at the Schenck Farmstead.

The Lenni Lenape are likely the descendants of these first inhabitants. This collection of several smaller tribes, each of which spoke dialects of the Algonquin language, were the first indigenous people that European settlers met in the region. Europeans dubbed this tribe the "Delaware," a name derived from English aristocrat Lord de la Warr. Although the majority of the Lenape were relocated thousands of miles away to Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Canada, a small contingent still lives in New Jersey. A further analysis of their culture and history in and around West Windsor and New Jersey is on the "Earliest Inhabitants & the Lenni Lenape" page.

The first Europeans to settle in New Jersey were Swedes, English, and the Dutch (who eventually developed such a unique culture that they became known as the "Jersey Dutch"), starting in the mid-1600s. Many of these families are still around today: the Schencks, Covenhovens, Perines, Bergens, Updikes, Vorhees, and Wyckoffs. The naming of historic village clusters such as Dutch Neck and Penns Neck still bear witness to the vernacular of this ethnic group. Even the architectural development of the region is influenced by Dutch practices, such as the assembly of the barn at the Schenck Farmstead.

Gravestones behind the Dutch Neck Presbyterian Church reveal some of the township's oldest Dutch and English families.

Gravestones behind the Dutch Neck Presbyterian Church reveal some of the township's oldest Dutch and English families.

West Windsor marked the southernmost settlement of concentrated Dutch Settlement of New Jersey, who generally did not settle past Assunpink Creek. Before the township's incorporation in 1797, the area that was to be known as West Windsor represented a particularly concentrated enclave of Jersey Dutch within Windsor Township.

With the annexation of land by the British in 1664, the English began to purchase more and more farmland. Families such as the Rogers and Hutchinsons began to populate the area. Because the English generally owned fewer slaves than the Dutch, agricultural practices began to change as well. So, too, did West Windsor's architecture.

For hundreds of years after these families arrived, West Windsor was a predominantly white and Christian community, composed mainly of the descendants of these Dutch and English settlers.

African Americans composed a small percentage of the population, comprised, largely, of slaves before New Jersey, and then the nation, abolished the practice. Afterwards, many found work as field hands. Interestingly, when Dutch Neck Elementary School was constructed in 1917, excavation unearthed members of the Pompey-Updike family, who themselves had been buried in an even older African American graveyard.

With the annexation of land by the British in 1664, the English began to purchase more and more farmland. Families such as the Rogers and Hutchinsons began to populate the area. Because the English generally owned fewer slaves than the Dutch, agricultural practices began to change as well. So, too, did West Windsor's architecture.

For hundreds of years after these families arrived, West Windsor was a predominantly white and Christian community, composed mainly of the descendants of these Dutch and English settlers.

African Americans composed a small percentage of the population, comprised, largely, of slaves before New Jersey, and then the nation, abolished the practice. Afterwards, many found work as field hands. Interestingly, when Dutch Neck Elementary School was constructed in 1917, excavation unearthed members of the Pompey-Updike family, who themselves had been buried in an even older African American graveyard.

A ball game in Glen Acres

A ball game in Glen Acres

Unfortunately, the Historical Society does not possess many comprehensive documents on the residency of minority groups before the last quarter of the 20th century; only some photographs and footage of said field hands (at the now-disappeared Shangle Farm) and documents indicating slave ownership are in our possession. Please contact us if you have more information on this subject!

In 1958, amid the national Civil Rights movement, West Windsor saw the construction of one of the state's first dedicated integrated neighborhoods - Glen Acres, at Glenview Drive (off of Alexander Road). This development proved a great case-study for the value of integration, with a noticeable lack of fences and a tight-knit community.

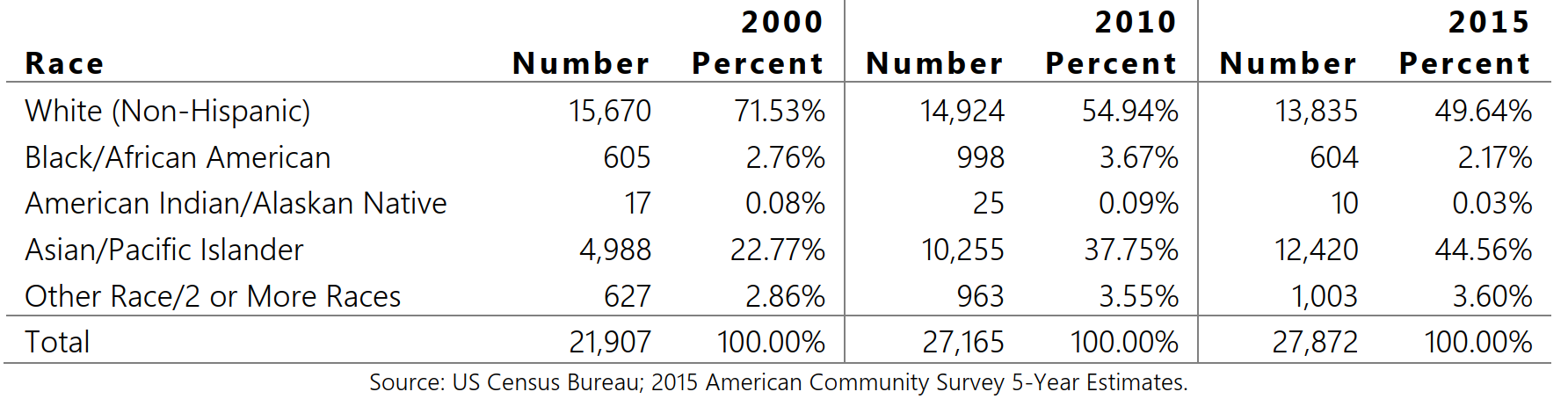

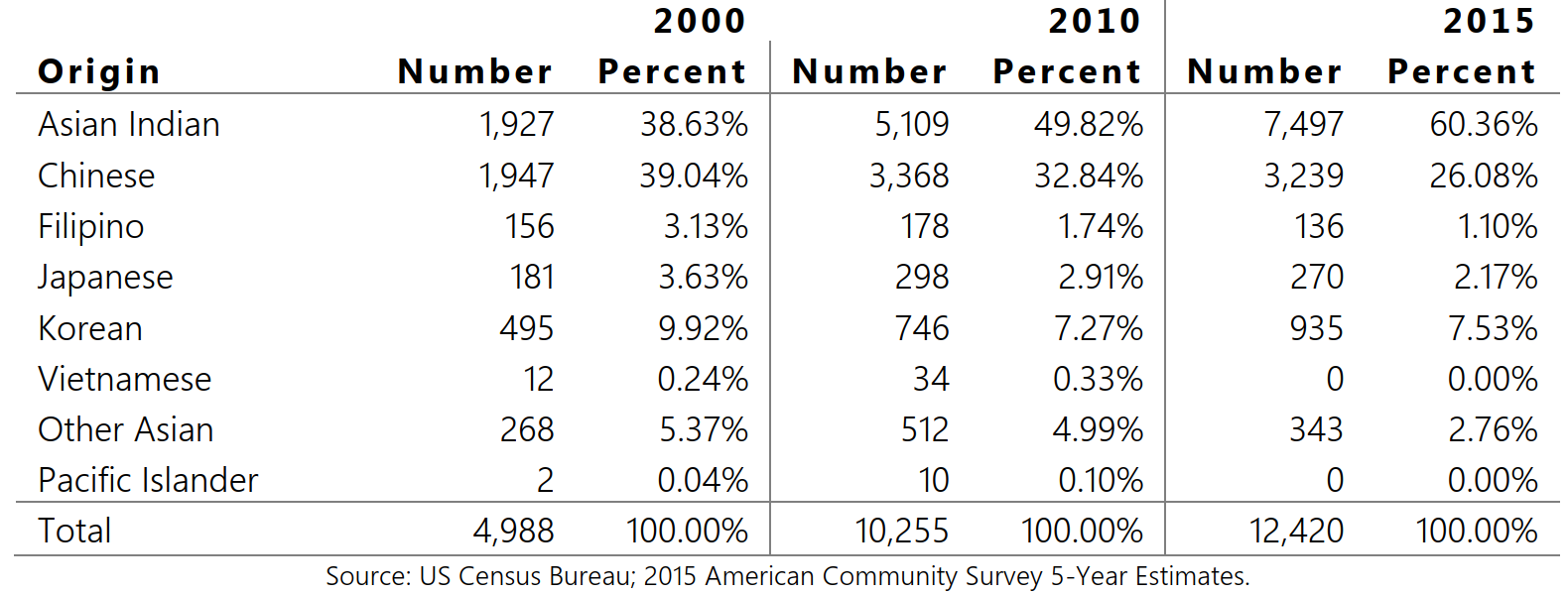

Within the next few decades, a bounty of different cultures - especially Indian and Chinese - began to represent more and more of the township's population. Particularly after 2000, these groups began to see increasing population representation. The two tables below, taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan, demonstrate this trend:

In 1958, amid the national Civil Rights movement, West Windsor saw the construction of one of the state's first dedicated integrated neighborhoods - Glen Acres, at Glenview Drive (off of Alexander Road). This development proved a great case-study for the value of integration, with a noticeable lack of fences and a tight-knit community.

Within the next few decades, a bounty of different cultures - especially Indian and Chinese - began to represent more and more of the township's population. Particularly after 2000, these groups began to see increasing population representation. The two tables below, taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan, demonstrate this trend:

Meanwhile the populations of both the American Indian/Alaskan Native (0.08% to 0.03%) and Black/African American residents (2.76% to 2.17%) have slightly decreased since 2000. So, too, has the percentage of Chinese residents dropped, from 39.04% to 26.08%. However, most dramatic is the non-Hispanic white population's decrease, from 71.53% in 2000 to 49.64% in 2015.

The increase in West Windsor's cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity has manifested in numerous ways - including multicultural festivals, restaurants, community groups, political representation, and school-based organizations. Recreation in West Windsor is also starting to change the township's physical landscape, beginning with a cricket pitch that was installed in the Community Park in 2016, following the surge of cricket teams throughout the township. It is now rare to find the field unoccupied by players enthusing in the popular international sport.

The increase in West Windsor's cultural, racial, and ethnic diversity has manifested in numerous ways - including multicultural festivals, restaurants, community groups, political representation, and school-based organizations. Recreation in West Windsor is also starting to change the township's physical landscape, beginning with a cricket pitch that was installed in the Community Park in 2016, following the surge of cricket teams throughout the township. It is now rare to find the field unoccupied by players enthusing in the popular international sport.

Beth Chaim

Beth Chaim

Most visible, however, is the construction of religious houses of worship due to the shift in the town's cultural makeup. The township's religious composition has historically been Christian. Two houses of in particular - the Dutch Neck Presbyterian Church (built in 1816 on the site of 1797 "(Dutch) Neck Meeting House") and Penns Neck's Princeton Baptist Church (1812) - are of historical note, serving as sites for devotion, community meetings, and even government meetings. More on their extensive histories are explored in their respective village web pages.

And so West Windsor remained a predominantly Christian community for over a century and a half.

It was not until 1965 that the next extant establishment - the Prince of Peace Lutheran Church on Princeton-Hightstown Road - opened its doors within West Windsor. In 1972, with the formation of the Beth Chaim congregation (which found its home on Village Road East in 1977) opened its doors to those seeking a Reform Jewish church, and ushered in an era of more diverse houses of worship. It was followed by the construction of the Princeton Meadow Church building in 1986, the Windsor Chapel in 1988, the Princeton Korean Community Church house of worship in 1991, Saint David the King in 1992, and the NextGen and the Disciplies Christian churches in 2008. More recently, in 2014, construction was completed on the mandir portion of a gargantuan BAPS Hindu complex in Robbinsville, New Jersey - just a few thousand feet outside of West Windsor's southern border. In May 2018, the Muslim Center of Greater Princeton - a mosque servicing over 1,000 practitioners of Islam - was constructed on Old Trenton Road, servicing the 20-year-old community. Finally, in 2019, The Bridge found its home in the Windsor Athletic Club's building. Note that many of these religious organizations are older than their buildings.

To explore these religious institutions' histories with further depth, navigate to the Religion section!

And so West Windsor remained a predominantly Christian community for over a century and a half.

It was not until 1965 that the next extant establishment - the Prince of Peace Lutheran Church on Princeton-Hightstown Road - opened its doors within West Windsor. In 1972, with the formation of the Beth Chaim congregation (which found its home on Village Road East in 1977) opened its doors to those seeking a Reform Jewish church, and ushered in an era of more diverse houses of worship. It was followed by the construction of the Princeton Meadow Church building in 1986, the Windsor Chapel in 1988, the Princeton Korean Community Church house of worship in 1991, Saint David the King in 1992, and the NextGen and the Disciplies Christian churches in 2008. More recently, in 2014, construction was completed on the mandir portion of a gargantuan BAPS Hindu complex in Robbinsville, New Jersey - just a few thousand feet outside of West Windsor's southern border. In May 2018, the Muslim Center of Greater Princeton - a mosque servicing over 1,000 practitioners of Islam - was constructed on Old Trenton Road, servicing the 20-year-old community. Finally, in 2019, The Bridge found its home in the Windsor Athletic Club's building. Note that many of these religious organizations are older than their buildings.

To explore these religious institutions' histories with further depth, navigate to the Religion section!

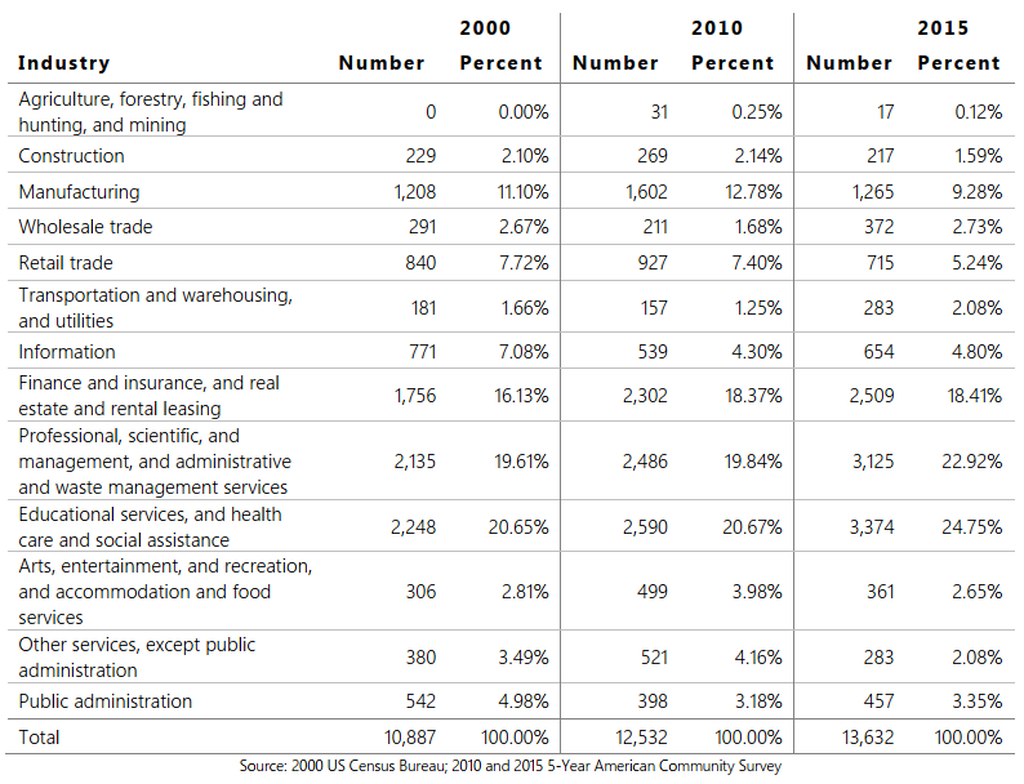

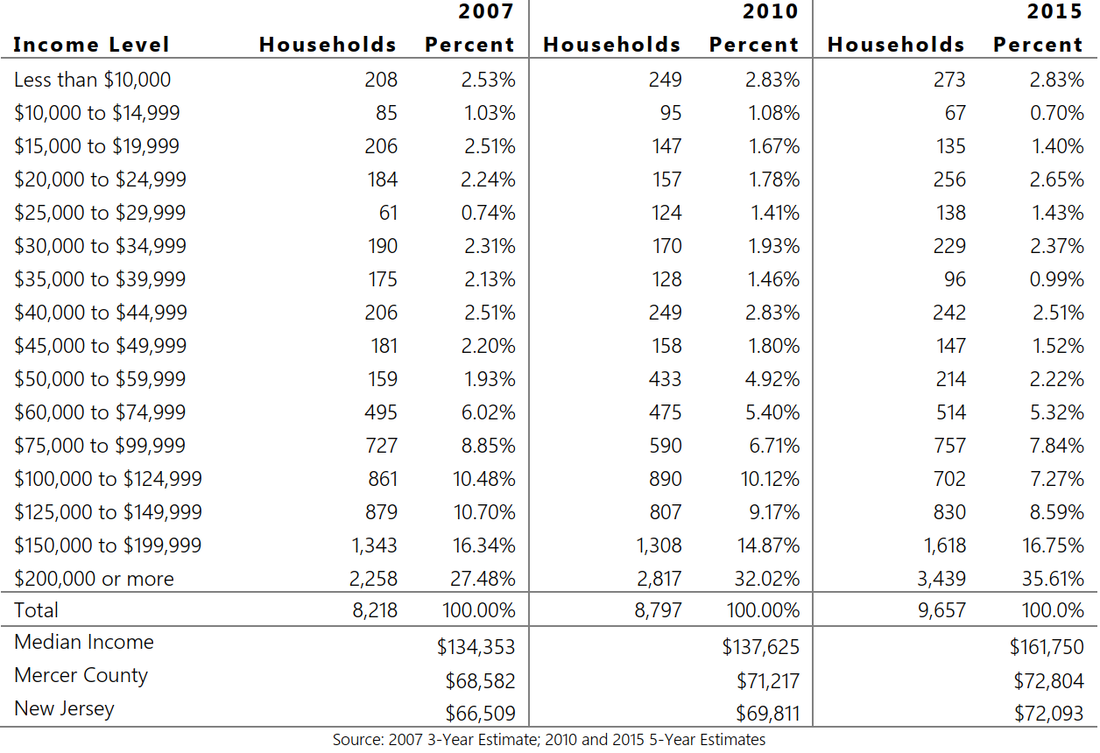

West Windsor's economic identity has also dramatically shifted from its agrarian roots. In 1960, 65 percent of the township's land was devoted to farming, and the economic profile of the township mimicked this dynamic. However, in 2000, let alone 2015, residents are employed in a significantly more diverse set of occupations and have seen their incomes rise over that 15 year period (note: both tables taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan):

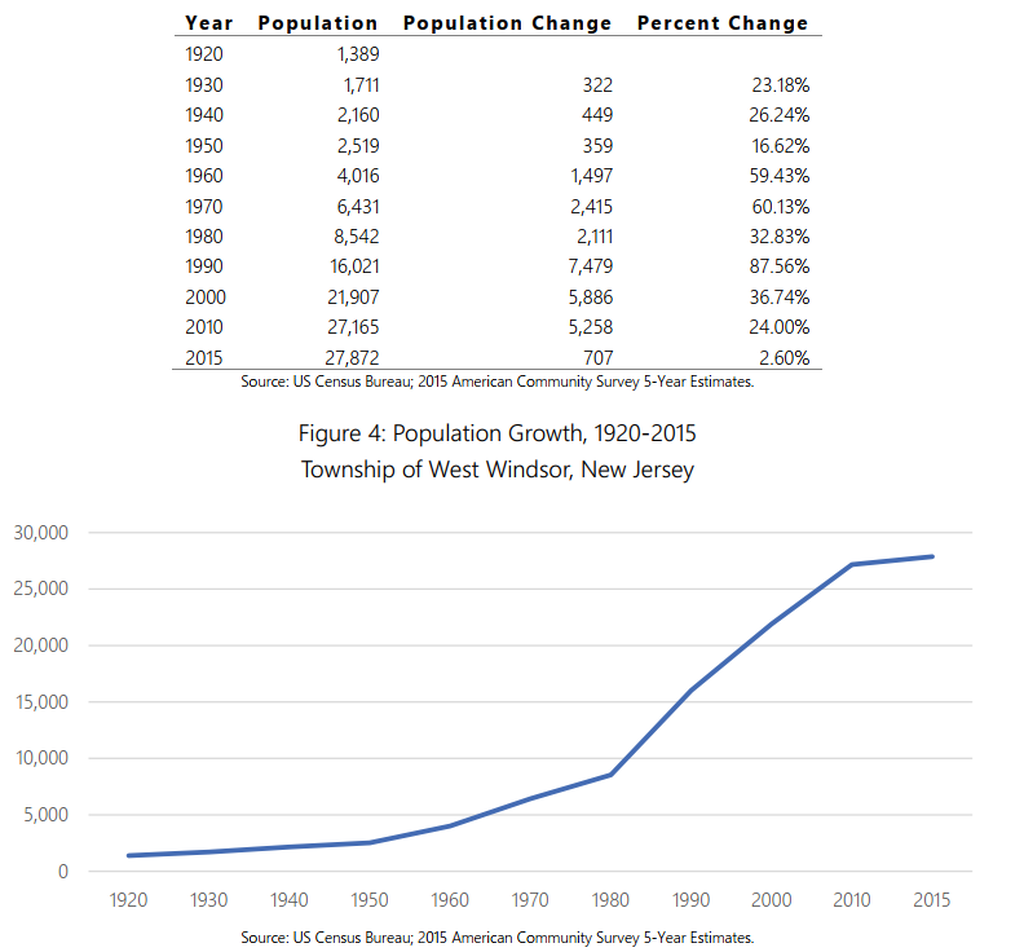

As shown by the table below (which was also taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan), West Windsor's overall population has also change dramatically since it was first settled. In 1920, only about 1,389 people called West Windsor home (after a downward trend from a peak of 2,129 in 1830!). The 1970 census records a population of only 6,431. Between 1980 and 2015, however, the township grew by over 218%, eventually housing 27,165 people and enjoying a bounty of new residents of a variety of nationalities, races, and cultures.

This influx of residents, however, dramatically changed the landscape of West Windsor, from a primarily agrarian township with only a dispersion of housing developments to a busy suburban town of almost 30,000 people. Consequently, the topology of West Windsor has changed: new schools have been constructed, housing developments have , roads have been widened, and This change can most notably be seen from aerial views of the township at specific locations: most notably along Old Trenton Road, Bear Brook Road, and Clarksville Road in the past 25 years, and by examining a road map of West Windsor from the early 1980s and contrasting it with today's map:

|

|

|

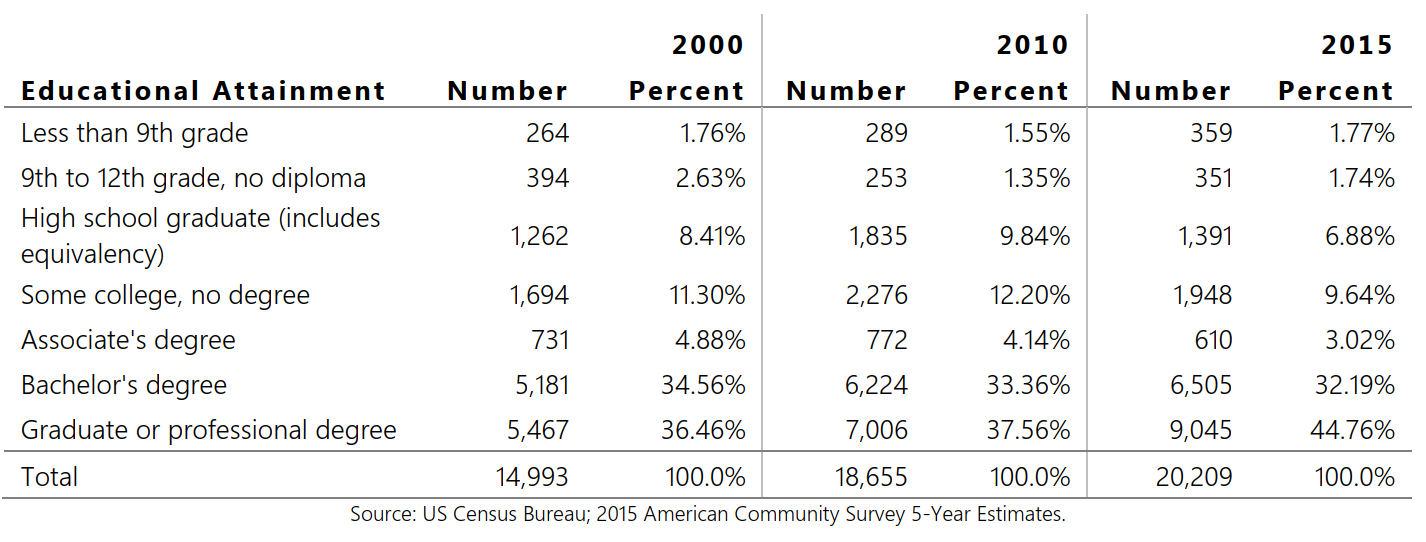

Nevertheless, West Windsor benefits from its unique diversity and population growth. For the religious, a variety of Christian, Muslim, Hindu, and Jewish sects offer a multitude of places of worship. Children raised in the township enjoy a culturally and racially-diverse, award-winning school district, and all residents live among a highly-educated populace (table taken from the township's 2018 reexamination of its master plan):

The dramatic changes experienced by West Windsor over the past few decades have dramatically altered its identity. From a sleepy, rural, predominantly white and Christian town to a thriving, diverse, suburban municipality of almost 30,000 residents . This change is invariably part of West Windsor's historical and current social fabric - a town in flux, evolving with its populace.