Historic Community: Penns Neck

Largely centered around Washington Road and Route 1 is one of West Windsor's oldest historic communities. This hamlet, named after its original colonial landowner - the legendary William Penn - developed as a stagecoach stop in the early 1800s and grew significantly in the 20th century. Although much has been lost over the years (especially along Route 1), the neighborhood still retains a strong sense of community. Explore Penns Neck and its historical buildings below!

In 2023, Paul Ligeti - then President of the Historical Society - presented on Penns Neck's history. Click here to watch the recording.

In 2023, Paul Ligeti - then President of the Historical Society - presented on Penns Neck's history. Click here to watch the recording.

Historical Overview

|

Penns Neck’s story begins with William Penn, famed Quaker and founder of Pennsylvania. In 1693, Penn acquired over 6,500 acres between the Assunpink Creek to the south the Millstone River to the north, the Stony Brook to the west, and what is now Penn-Lyle Road to the east.[1] This territory was known as "Penns Neck" as early as 1737, if not earlier.[2] It essentially means "William Penn's territory" (think of "neck" as in the phrase "neck of the woods"). The tract was also called "Williamsburg," albeit with less popularity and this name died out over time.[3] The Penn family held this immense tract as absentee landowners until 1737, when they sold it to two Dutch men from Monmouth County: Garret Schenck and John Kovenhoven.[4] Soon afterwards, their families began to settle the area.

The Schencks and Kovenhovens, like many other early West Windsor settlers, were descendants of pioneers who had immigrated to the New World colony of New Netherland (around present-day New York and Jersey City) in the mid-1600s.[5],[6] Here in mid-1700s Penns Neck, Garret and John divided up their vast territory into individual plots of several hundred acres each for their children and relatives.[7] These descendants built sturdy houses of timber and stone dotting endless vistas of new farmland - regrettably, also tilled by slave labor for many generations, as with the rest of the Windsor Township at the time.[8] By 1746, early families had established a local burial ground[9] and, reputedly before 1760, a schoolhouse.[10] |

|

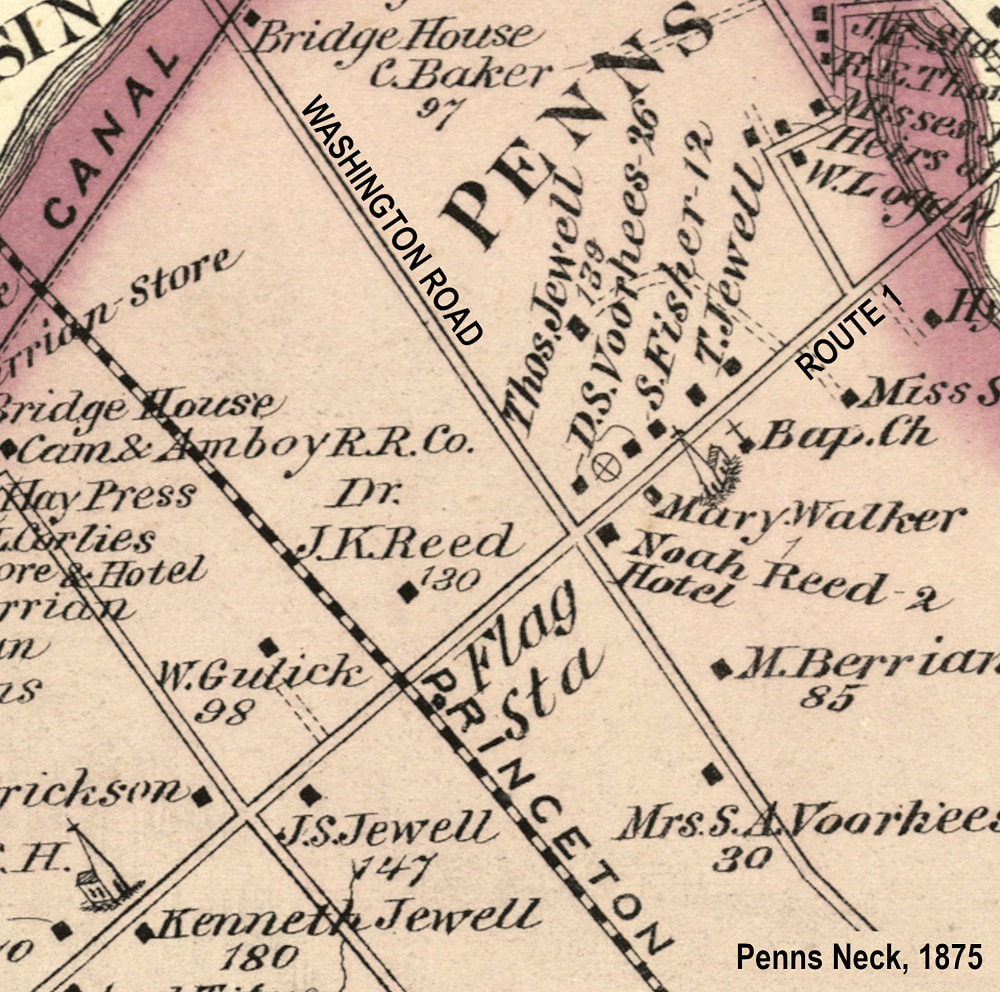

Throughout the 1700s, other families settled here as well. Names such as "Jewell," "Fisher," "Reed," "Logan," "Wilson," "Cruser," "Stout," "Hight," and more are commonly seen on local gravestones[11],[12] and referenced in old manuscripts.[13] Following the chartering of Route 1 in 1804 and the public surveying of Washington Road around the same time, these families began to consider the crossroads the nexus of the community. In fact, in 1807, William Kovenhoven established the Red Lion Inn at the intersection.[14] Five years later, the Princeton Baptist Church rose next door to serve an already well-established congregation.[15] These two institutions were the social, spiritual, and political heart of the community for generations (in fact, the inn was a common site for Township Committee meetings[16]), and still stand at the time of this writing (2023) as two of just a handful of West Windsor buildings on the National Register of Historic Places.[17]

By the mid-1800s, a second inn, general store, blacksmith, wheelwright shop, harness shop, wagon repairer’s shop and about a dozen residences had also appeared around the intersection.[18] This dynamic - of an agricultural community loosely centered on this small dirt crossroads - would be the defining identity of Penns Neck for decades to come. Residents also enjoyed horse racing[19] and had easy access into Princeton for leisure and business via the roads as well as a station stop here along the 1860s-era Dinky line until goo1971.[20],[21] |

|

The 1920s saw the start of Penns Neck's suburban growth, with developers capitalizing on proximity to Route 1 and Princeton. Around the 1920s, Margaret Rule, who had inherited a tract from James S. Fisher, subdivided her property into residential lots on either side of the street now known as Fisher Place.[22] In 1926, Julius Wildermuth had plans approved to develop his own land on the south side of Washington Road into the 42-tract "Varsity View."[23] The following year, Fred Waters established the 150-parcel "Princeton Manor" north of Washington Road.[24] Newcomer families purchased these plots, constructed their own homes, and began to form a suburban community lining Washington Road as well as adjacent roads named for local farmers (Mather Avenue, Wilder Avenue, Fisher Place) and idyllic concepts (Morning Sun, Fairview, Manor, and Varsity Avenues).[25],[26]

In 1917, the Penns Neck School was built at Alexander Road and Route 1 to replace the older 1800s-era small wooden schoolhouse.[27] Around five or six years later, the Penns Neck Community Club was established to “aid the civic, moral, intellectual, and social welfare of the community.”[28],[29] Later in the 1920s, the Washington Road Elm Allee was planted as an arboreal "gateway" between West Windsor and Princeton, and still grows as another landmark on the National Register of Historic Places.[30] Also around this time was a failed movement to rename Penns Neck (suggestions included "Princeton Highlands, Varsity Heights, South Princeton, Princeton Terrace, and Penns Crest").[31] What succeeded, however, was an initiative in 1931 to turn the 4-way intersection of Route 1 and Washington Road turned into a pure traffic circle in response to increased traffic (and more frequent accidents).[32] |

|

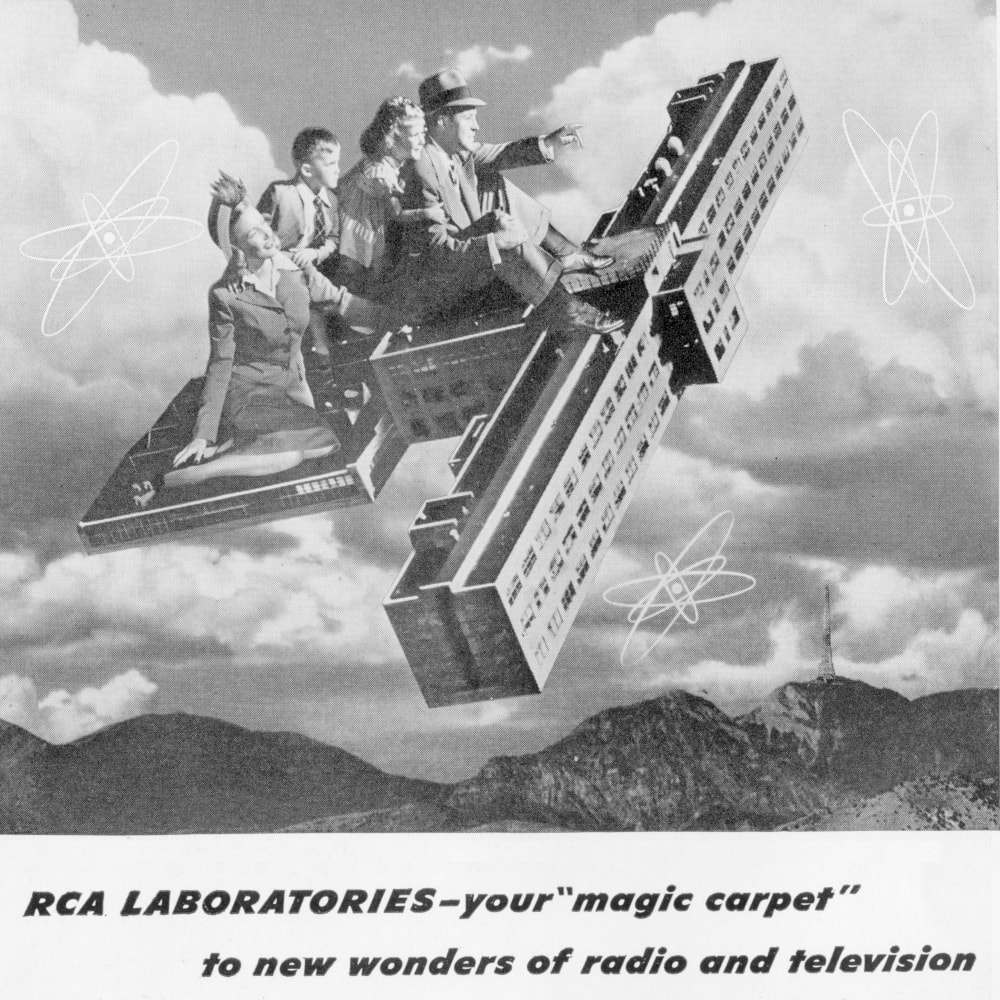

The 1940s saw further growth when the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) opened a campus on the old Engelke and Olden farms north of Fisher Place in 1942.[33] Later called the David Sarnoff Research Center,[33] it spearheaded countless nationally-significant innovations in communication, consumer products, national defense systems, "Space Race" technology, and more.[35] It, and the long-gone Heyden Chemical Corporation nearby,[36] employed many local residents.

In 1959, the traffic circle was redesigned to have Route 1 run through it (this is the current configuration in 2023).[37] By the early 1960s, the circle had become surrounded by a variety of businesses. Gas and automobile service stations dominated its four corners,[38] alongside a few diners at various points in time,[39],[40] at least one restaurant,[41] a furniture store,[42] houses,[43] and more. Similarly, by this time, several establishments had set up shop along Washington Road east of Route 1, including a butcher/grocery store,[44] a plant/flower shop,[45] a swimming pool,[46] a tavern,[47] and an automobile service station.[48] During the last quarter of the 20th century and into the 21st, most of the area’s farmland was replaced by office parks (notably Carnegie Center), shopping districts, and housing developments (primarily along Canal Pointe Boulevard).[49],[50] The "Longmeadow" development saw dozens of houses built along Wallingford Drive, Coventry Circle, and Fieldstone Road south of Washington Road.[51] All of this growth inevitably led to challenges for Penns Neck, especially centered around flooding and traffic. Numerous proposals to solve local congestion - notably, a "Millstone Bypass"[52] - have come and gone, but the community continues to experience congestion - especially at the traffic circle, which in 2023 features only a telephone company and a gas station. |

|

Over the decades, most of Penns Neck's 1700s-era and 1800s-era sites have been demolished or lost to the ravages of time and development. No farmland remains directly around the crossroads. The community's image is largely one of congestion along a busy state highway (Route 1), in contrast with the sleepy rutted dirt farm lanes of yore.

However, the community's most important historical remnants do remain. Notably, the mid-1700s Penns Neck Cemetery still stands about 1/3 of a mile north of the crossroads (albeit now in the center of Princeton University's "West Windsor Meadows Neighborhood". The Princeton Baptist Church and Red Lion Inn still overlook the traffic circle. SRI International now occupies the former David Sarnoff Research Center and continues to use it as an innovation campus. And a handful of old businesses still line Washington Road, surrounded by hundreds of houses constructed over the decades by local families. Most importantly, Penns Neck retains a sense of neighborhood and identity - its best defense against change and destruction. Its story, dating back to the town’s earliest wave of settlement, is integral to the broader history of West Windsor and will hopefully be preserved for generations to come. |

Historical Penns Neck Landmarks

Click on the images below to explore many Penns Neck landmarks! We recommend reading them in order. More sites may be added as research improves.

Bibliography

- Hamilton, Andrew, John Barclay, David Mundie, Thomas Warne, John Reid, George Willocks, and William Penn. Ms. Indenture. New Jersey State Archives, 1693. Conveyance of Penns Neck tract to William Penn from the Proprietors of East New Jersey - May 16, 1693 (Bears date May 16, 1692 due to Julian/Gregorian Calendar Differences). In New Jersey State Archives: E (EJ): Folio 45 (SSTSE023)

- Schenck, Garret, and Albert Schenck. “Indenture.” West Windsor, November 28, 1737. November 28, 1731 Deed from Garret Schenck to Albert Schenck - found in New Jersey State Archives, East Jersey Deeds Volume F-2 p. 461.

- Wilson, Peter. “Minutes of the William’s Burrough Baptist Church, 1812-1852.” West Windsor, NJ: Princeton Baptist Church, 1812.

- Schenck, Garret, John Covenhoven, Thomas Penn, Richard Penn, and John Penn. Indenture. New Jersey State Archives, 1737. Deed of 6,500 acres from heirs (sons) of William Penn to Garret Schenck and John Covenhoven. Located in New Jersey State Archives F-2 (EJ): Folio 380 (SSTSE023)

- Snyder, John Parr. The Story of New Jersey’s Civil Boundaries, 1606-1968. Trenton: New Jersey Dept. of Environmental Protection, Division of Water Resources, Geological Survey, 1969.

- Ibid.

- “Penn’s Neck.” Essay. In Old Princeton’s Neighbors. Princeton, NJ: Graphic Arts Press,1939. Written by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project.

- “Schedule of the Whole Number of Persons within the Several Districts of the United States, Taken According to ‘An Act Providing for the Enumeration of the Inhabitants of the United States;” Passed March the 1st, 1790.” Windsor, 1790.

- "Penn's Neck.” Essay. In Old Princeton’s Neighbors. Princeton, NJ: Graphic Arts Press , 1939. Written by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project.

- “Penns Neck Cemetery.” West Windsor, NJ 08540: Princeton University’s “Lake Campus,” Penns Neck, n.d. Contains gravestones of West Windsor residents from 1746 to 1941.

- Ibid.

- Princeton Baptist Church. (n.d.). Princeton Baptist Church graveyard. West Windsor. Princeton Baptist Church graveyard gravestones, which often list birth dates, death dates, and ages of those buried there - including those of many of West Windsor's oldest families.

- Wilson, Peter. “Minutes of the William’s Burrough Baptist Church, 1812-1852.” West Windsor, NJ: Princeton Baptist Church, 1812.

- Joline, John. Ms. West Windsor, 1807. John Joline’s application for a tavern license. Located in the New Jersey State Archive’s Manuscripts Room - Middlesex County Tavern License collection (1758-1826).

- Wilson, Peter. “Minutes of the William’s Burrough Baptist Church, 1812-1852.” West Windsor, NJ: Princeton Baptist Church, 1812.

- “West Windsor Township Meeting Minutes, 1797-2012.,” n.d. Original Township Committee meeting minute database located in the Municipal Center.

- “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form.” West Windsor, November 28, 1989. For the Princeton Baptist Church and Red Lion Inn. Approved.

- Woodward, Evan Morrison, and John Frelinghuysen Hageman. History of Burlington and Mercer Counties with Biographical Sketches of Many of Their Pioneers and Prominent Men. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts & Peck, 1883.

- "Penn's Neck Races." Trenton State Gazette. September 12, 1835.

- Messer, David W, and Charles S Roberts. Essay. In Triumph V Philadelphia to New York 1830-2002, 1st ed., 84–93. Barbard, Roberts and Co., Inc, 2002.

- Baer, Christopher T. “A GENERAL CHRONOLOGY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA RAILROAD COMPANY ITS PREDECESSORS AND SUCCESSORS AND ITS HISTORICAL CONTEXT,” April 2015. Retrieved via the following URL: http://www.prrths.com/newprr_files/Hagley/PRR1971.pdf

- “Penns Neck Area EIS - West Windsor and Princeton Townships, Mercer County and Plainsboro Township, Middlesex County, New Jersey - Historic Architectural Survey - Volume 2 of 2,” May 2003. Prepared for the New Jersey Department of Transportation by John Milner Associates (Architects/Archaeologists/Planners).

- Wildermuth, Julius. “Varsity View.” Map. Mercer County Clerk’s Office Map Collection. Princeton, New Jersey: Sincerbeaux & Moore, Civil Engineers, 1926. Map No. 517 in the Mercer County Clerk's Office map collection.

- Walters, Fred T. “Princeton Manor.” Map. Mercer County Clerk’s Office Map Collection. Princeton, New Jersey: Sincerbeaux & Moore, Civil Engineers, 1927. Map No. 522 in the Mercer County Clerk's Office map collection.

- Wildermuth, Julius. “Varsity View.” Map. Mercer County Clerk’s Office Map Collection. Princeton, New Jersey: Sincerbeaux & Moore, Civil Engineers, 1926. Map No. 517 in the Mercer County Clerk's Office map collection.

- Walters, Fred T. “Princeton Manor.” Map. Mercer County Clerk’s Office Map Collection. Princeton, New Jersey: Sincerbeaux & Moore, Civil Engineers, 1927. Map No. 522 in the Mercer County Clerk's Office map collection.

- “To Vote on Sale of Four Schools.” Trenton Evening Times, October 29, 1917. Mentions that "...the children of the township (are) now being taught in the fine new graded schools at Dutch Neck and Penn's Grove."

- “Penn’s Neck.” Essay. In Old Princeton’s Neighbors. Princeton, NJ: Graphic Arts Press,1939. Written by the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Writers’ Project.

- "Penns Neck Festval." Trenton Evening Tims. May 30, 1923.

- Hand, Susanne C. “National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Washington Road Elm Allee.” Princeton, New Jersey, June 30, 1998. Entered into the National Historic Register on January 4, 1999.

- "Penns Neck May Bear New Name." Princeton Herald. October 28, 1927.

- "Good Progress Made in Building New Penns Neck Traffic Circle." Trenton evening Times. November 28, 1931.

- The RCA Laboratories - The David Sarnoff Research Center. West Windsor, New Jersey: RCA Laboratories Division, 1957. Accessed via Rutgers University Libraries website: https://doi.org/doi:10.7282/T3X34VQS

- 1942-1967 Twenty-Five Years at RCA Laboratories. RCA , 1967. Retrieved from: https://worldradiohistory.com/ARCHIVE-RCA/RCA-Engineer/25-Years-At-RCA-Labs-1942-1967.pdf

- Warner, J C, E W Engstrom, and J Hillier. RCA an historical perspective. RCA, 1978. Retrieved from: https://worldradiohistory.com/BOOKSHELF-ARH/Technology/RCA-Books/RCA-An-Historical-Perspective.pdf

- "Penicillin Production Here is Highly Praised." Princeton Herald. November 22, 1946.

- "Penns Neck Circle Gone." Trenton Sunday Times-Advertiser. November 15, 1959.

- Schrader, Howard E. “Photographs of Route 1 from Howard E. Schrader.” West Windsor, New Jersey: Archives of the Historical Society of West Windsor at the West Windsor History Museum, July 1962. Series of photographs showing various businesses at the Penns Neck traffic circle in 1962.

- Ibid.

- "Princeton Grill & Diner." Princeton News (Special Advertising Feature Section). March 2, 1939.

- Schrader, Howard E. “Photographs of Route 1 from Howard E. Schrader.” West Windsor, New Jersey: Archives of the Historical Society of West Windsor at the West Windsor History Museum, July 1962. Series of photographs showing various businesses at the Penns Neck traffic circle in 1962.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- J. T. Yeager, Auctioneer. “Public Auction.” Town Topics. Princeton, NJ, March 27, 1955.

- Verne Desautelle. “V. N. Desautelle Florist & Greenhouse.” Princeton Herald. Princeton, NJ, January 24, 1947.

- Princeton Swim Club. “Princeton Swim Club.” Town Topics. Princeton, NJ, June 19, 1960.

- "Bear Brook Tavern Popular for Fin Pizza, Italian Specialties, Drinks, Happy Times." Princeton Herald. Novembr 21, 1963.

- Penns Neck Texaco. “BIG NEWS Penns Neck Texaco Opens Saturday, November 30.” Town Topics. Princeton, NJ, November 28, 1963.

- "West Windsor Aerial Photography Composite Map, 1975.” Map. Historical Society of West Windsor - Map Archives. West Windsor, NJ, 1975.

- "West Windsor Aerial Photography Composite Map, 1985.” Map. Historical Society of West Windsor - Map Archives. West Windsor, NJ, 1985.

- Ibid.

- “Draft Environmental Assessment/Section 4(f) Evaluation.” Route 1/penns neck area. New Jersey Department of Transportation, September 2000. https://www.state.nj.us/transportation/works/studies/pennsneck/pdf/section_1.pdf.