West Windsor's Railroad

Princeton Junction Train Station, April 2022.

Princeton Junction Train Station, April 2022.

Running through West Windsor is the Northeast Corridor - one of the United State's busiest train routes. This line, with origins in the 1830s, stops at the heavily-trafficked Princeton Junction Train Station. Opened during the Civil War, this station was the locale around which the West Windsor community of Princeton Junction grew. Both station and railroad have immensely impacted West Windsor's development and identity over many generations. Scroll down to learn more!

Historical Overview

|

The tale of rail starts in the early 1800s. At this time, only two transportation systems existed in town: footpaths and roads. These were rudimentary, slow methods of transportation, and had little capability to move large quantities of commodities or people. Thus, an alternative was needed.

On February 4, 1830, the Camden and Amboy Railroad and Transportation Company incorporated to fill this void. However, this was also a time when inland water transportation was becoming popular. That very same day, the "Delaware and Raritan Canal" organized as well. Soon, the two transportation systems - rail and canal - were merged into one entity - the "Joint Companies" - that protected against a self-destructive rivalry.[1] |

|

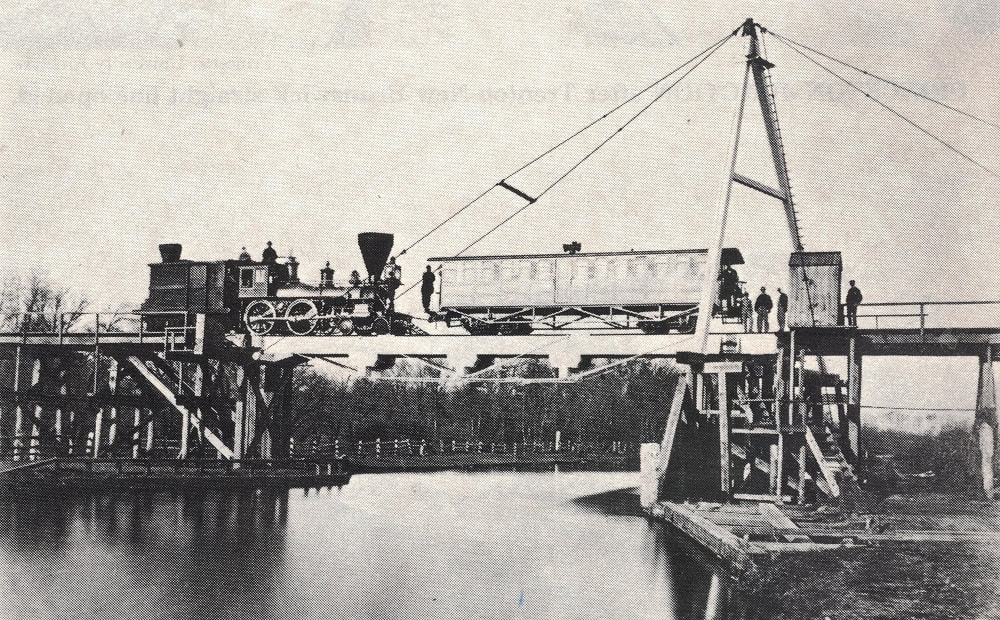

By 1834, the Delaware and Raritan Canal had been dug to provide uninterrupted access from Bordentown to New Brunswick.[2] Meanwhile, the Camden and Amboy Railroad was forming a cross-state rail network, linking most of New Jersey's major cities to one another. In 1839, railroad tracks were laid along the eastern bank of the Delaware and Raritan Canal where it ran through West Windsor.[3]

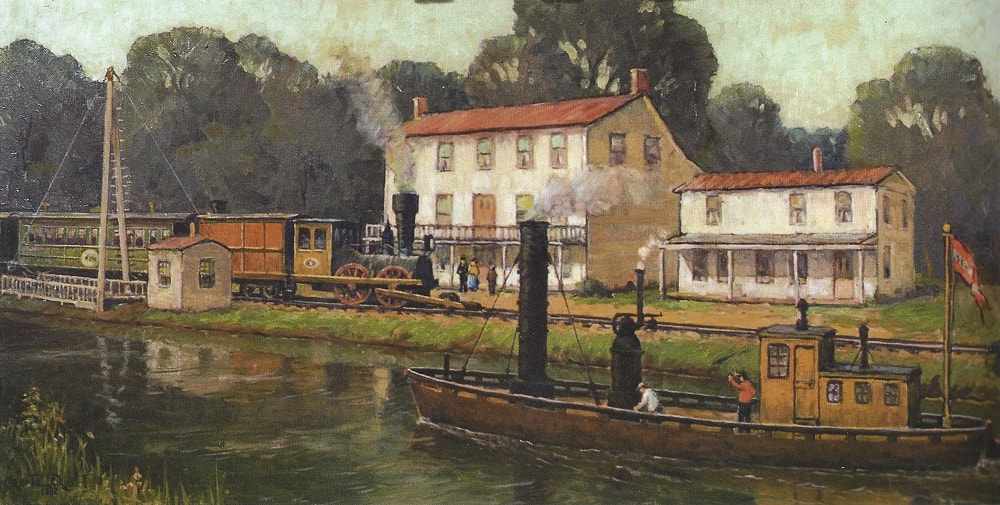

Over the next few decades, canal and rail worked hand-in-hand to transport millions of tons of cargo - and countless people - across New Jersey.[4] This fueled the rise of two communities: Princeton Basin (where Alexander Road crosses the canal) and Port Mercer (where Quakerbridge Road crosses the canal). Both thrived as industrial hubs, with factories, bridge-tenders' houses, hotels, houses, and more. And, of course, both featured stops for the canal and rail for onloading and offloading of people and cargo.[5] |

|

However, by the 1860s, the railroad’s directors decided that a more direct route was a smart investment. After much political debate, in 1863/4, the Camden and Amboy railroad was relocated eastward, where a straighter route could accommodate newer, faster, larger, and more powerful trains. This “new” alignment - is known as the “Northeast Corridor."[6]

This realignment was the death of the canal, which now had to compete with rail - as well as the decline of Princeton Basin and Port Mercer. You can learn more about this dynamic by clicking here. The relocation also upset many Princeton residents, who would soon have less direct rail access to other parts of the state, as well as Philadelphia and New York. After much political pressure, the 2.7-mile “Princeton Branch” (also known as the “Dinky” or “Princeton Junction and Back”) was opened in 1865.[7] It had several stops, including one in the West Windsor neighborhood of Penns Neck and one in Princeton Basin.[8] |

|

The mainline's relocation gave rise to one of West Windsor's best-known historic communities: "Princeton Junction." This locale was so named because it grew around the "junction" (intersection) of the mainline and the Dinky Line, as well as the train station itself (constructed circa 1863). Old Princeton Junction - some of whose earliest buildings still stand (in 2023) along Station Drive - included a hotel, warehouses, farms, general store/post office, houses, and more.[9] It catered to the railroad and grew, over generations, into West Windsor's commercial and transportation hub.

The Princeton Junction Train Station originally featured of a one-story ticket building with large overhanging eaves, located on the southbound (western) side of the tracks. A pedestrian bridge nearby went over the railroad tracks, although many locals chose to just walk across the line directly if they wanted to get to the other side.[10] |

|

After burning down in 1892, the original station building was replaced by a two-story structure. This building - still on the southbound side of the tracks - had a six-room apartment on the top floor for the station master and stood across the tracks from a small waiting booth.[11] In 1928, this waiting booth was replaced by a brick-and-mortar building.[12] By the 1930s (if not earlier), the "Nassau Interlock Tower" was also constructed on the northbound side of the tracks to help signal to trains coming into the station.[13]

The two-story station building burned down in 1953, purportedly due to mice chewing on old electrical wires.[14] It was replaced by a smaller waiting room and covered arcade, and the ticket purchases moved to the northbound brick-and-mortar waiting room.[15] Finally, in 1987, the current (in 2023) two-story ticket building with newsstand-store underneath was erected on the northbound side, next to the waiting room. A new Dinky line waiting booth also replaced the 1954-era structure at this time.[16] The 1928-era northbound waiting room was demolished within the next several years.[17] |

|

From its inception, the train station was an integral part of West Windsor’s identity and history. It allowed farmers and others a chance to sell their wares to distant markets. It provided express travel to metropolises such as New York and Philadelphia for recreational, educational, and employment opportunities. It has hosted legendary orators such as William Jennings Bryan (for his Presidential campaign stop in 1900).[18] Woodrow Wilson used it as his main point of connection into Princeton.[19] Longtime residents may also remember the funeral procession of former Attorney General and presidential hopeful Robert F. Kennedy stopping at the station in 1968.[20] Other prominent figures have doubtless passed through the station.

West Windsor’s first planned development was constructed starting in 1916, just south of the train station. Here, the neighborhood of "Berrien City" arose. Residences were laid out in uniform lots and appealed to those looking for easy access to the train station.[21] Legendary Nobel Prize and Abel Prize Winner John Forbes Nash – subject of a book and movie, both titled “A Beautiful Mind” - lived here for decades until his and his wife’s (Alicia) death in 2015.[22],[23] |

|

Today, the Princeton Junction Train Station remains one of the busier stops along the Northeast Corridor - itself one of the United States' most heavily-trafficked railroads, connecting the New York and (ultimately) Philadelphia metropolitan regions as part of a broader East Coast rail network. The station has drawn many thousands to move to West Windsor over the decades, significantly contributing to its growth over many generations. It, and the broader community of Princeton Junction, indelibly persist as indelible elements of West Windsor's rich history.

|

Bibliography

- Veit, Richard F. The Old Canals of New Jersey: A Historical Geography. Little Falls, NJ: New Jersey Geographical Press, 1963.

- “Delaware Raritan Canal Commission.” History. Delaware and Raritan Canal Commission. Accessed March 27, 2022. https://www.nj.gov/dep/drcc/about-canal/history/.

- Freeman, Leslie, Jr. E. “The New Jersey Railroad and Transportation Company.” The Railway and Locomotive Historical Society Bulletin 88, May 1953.

- “Delaware Raritan Canal Commission.” History. Delaware and Raritan Canal Commission. Accessed March 27, 2022. https://www.nj.gov/dep/drcc/about-canal/history/.

- "West Windsor Township.” Map. 1875 Historical Atlas of Mercer County, New Jersey - Map of West Windsor. Philadelphia, PA: Everts & Stuart, 1875. https://www.loc.gov/item/2010587333/.

- "Camden and Amboy Railroad/Delaware and Raritan Canal Companies Minutes of the Joint Board of Directors and the Executive Committee, 1831 - 1872,” n.d. Located at the New Jersey State Archive’s Manuscripts Room. Accessed February 28, 2022.

- Ibid.

- “West Windsor Township.” Map. 1875 Historical Atlas of Mercer County, New Jersey - Map of West Windsor. Philadelphia, PA: Everts & Stuart, 1875. https://www. loc.gov/item/2010587333/.

- Ibid.

- Princeton Junction Train Station, Mid-Late 1800s. Photograph. West Windsor, NJ, n.d. West Windsor History Museum.

- “Broadside,” 1998. Newsletter about the history of Princeton Junction (Part 2 of a 2-part series) produced by the Historical Society of West Windsor.

- ESRI ArcGIS Map Viewer - NJ 1930 Black & White Imagery,” n.d. Online interactive map viewer published by ESRI. One layer shows NJ 1930 black & white imagery - including in West Windsor. Accessed via the url: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/mapviewer/index.html?layers=4e7de8d868c248f99c3fddc5bf8c0386.

- “Penns Neck Area EIS - West Windsor and Princeton Townships, Mercer County and Plainsboro Township, Middlesex County, New Jersey - Historic Architectural Survey - Volume 2 of 2,” May 2003. Prepared for the New Jersey Department of Transportation by John Milner Associates (Architects/Archaeologists/Planners).

- “Fire Consumes Princeton Junction Station.” Trenton Evening Times, December 28, 1953.

- "New Rail Waiting Station at Princeton Jct.” Trenton Evening Times, September 29, 1954.

- Princeton Junction Train Station, 1987. Photograph. West Windsor, NJ, n.d. West Windsor History Museum.

- Personal recollections of Paul Ligeti, the author of this article, who grew up here starting in 1993 and does not recall ever seeing this building.

- “A Record Made.” Grand Forks Daily Herald, October 26, 1900.

- “Wilson Spends Two Years at a Railroad Depot.” Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, November 12, 1912.

- Taylor, Alan. “A Portrait of America: Watching Robert F. Kennedy’s Funeral Train Pass By.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, June 7, 2018. https://www.theatlantic. com/photo/2018/06/rfks-funeral-train-in-photos/562238/.

- Sincerbeaux, C. S. “Map Showing Plan of Lots for Scott Berrien Esq.” Map. West Windsor, New Jersey, 1916.

- Ayres, Karen. “Nashes Make Plea to Spare Their Home.” The Times. March 13, 2002.

- John, Alicia Nash Remembered After Fatal Crash.” Town Topics. May 27, 2015.