Architecture

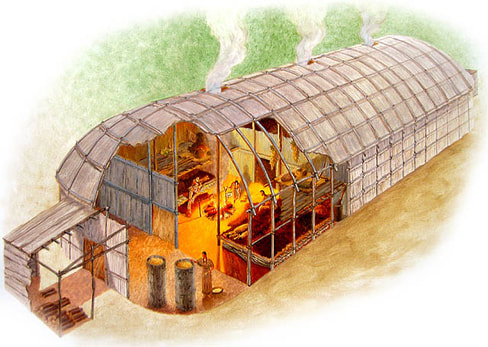

Traditional Native American long house

Traditional Native American long house

Overview

While the study of residential architecture may seem tangential to West Windsor's history, buildings are actually important windows into the past: like maps, documents, and oral histories, they are vital primary sources. Historical aesthetics give a look into broader art, and thus philosophical movements, that prevailed when various buildings were erected. Their assemblies are informed by the technologies and trades locally available at the time. Furthermore, layout, materials, level of detail, and size provide insight into the utility of a building, and the socioeconomic status of its owner.

The first semi-permanent constructs within the township were the longhouses of the Lenni Lenape. These deep dwellings provided shelter for multiple families within a clan, and were constructed of wood, rope, and mud. Unfortunately, nothing remains of these traditional structures which once called the area home for thousands of years.

While the study of residential architecture may seem tangential to West Windsor's history, buildings are actually important windows into the past: like maps, documents, and oral histories, they are vital primary sources. Historical aesthetics give a look into broader art, and thus philosophical movements, that prevailed when various buildings were erected. Their assemblies are informed by the technologies and trades locally available at the time. Furthermore, layout, materials, level of detail, and size provide insight into the utility of a building, and the socioeconomic status of its owner.

The first semi-permanent constructs within the township were the longhouses of the Lenni Lenape. These deep dwellings provided shelter for multiple families within a clan, and were constructed of wood, rope, and mud. Unfortunately, nothing remains of these traditional structures which once called the area home for thousands of years.

Due to West Windsor's location at the western edge of the inner coastal plain, its flat land and forests provided a prime local and material supply for the construction of wooden buildings. This contrasts with its neighbors Princeton and Lawrence, whose stone was often quarried to construct more solid edifices. Only one ancient house in West Windsor - the Garret Schenck House, constructed in the mid-1700s in Penns Neck - was built of stone, but was sadly torn down around the turn of the 20th century.

While the Jersey Dutch - West Windsor's first European settlers - are meagerly represented in the architecture of our township, their heritage still lingers on in the township's oldest buildings. Traditional Dutch houses from the 1600s and 1700s are typified by 1.5 story houses with steep, low-slung roofs sometimes with flared eaves. These houses were utilitarian, containing a hearth on the ground floor and sleeping loft in the half-story above. Three notable examples include:

While the Jersey Dutch - West Windsor's first European settlers - are meagerly represented in the architecture of our township, their heritage still lingers on in the township's oldest buildings. Traditional Dutch houses from the 1600s and 1700s are typified by 1.5 story houses with steep, low-slung roofs sometimes with flared eaves. These houses were utilitarian, containing a hearth on the ground floor and sleeping loft in the half-story above. Three notable examples include:

Ladyfaire

Ladyfaire

- 429 Clarksville Road - also known as "Ladyfaire," this house may be the oldest building in the township. Reputedly constructed in the late 1600s, it is a perfect representation of the evolution of West Windsor's architecture. The house was built in three parts - the oldest is closest to the road and supposedly dates from the 1690s, the middle section dates from the mid-1700s, and the last section from the mid-1800s. It is the most ancient part that is of Dutch construction, exhibiting the classic 1.5 story, low-slung gabled-roof style. Its hearth was removed at some point in the past, and the interior modernized, but its memory remains in the form of a rubble wall facing the road. More information on this house can be found here!

Schenck Farmstead Barn

Schenck Farmstead Barn

- 50 Southfield Road - of a Dutch-English hybrid architectural style, the mid-1700s barn at the Schenck Farmstead is representative of the transformation of cultures that would occur when the British started moving into the area in the late 1600s. It combined the assembly techniques of both countries, utilizing a now rare form of traditional Dutch architecture that used no iron fasteners (nails, bolts, etc.), due to the expenses then associated with metalworking. Rather, wooden beams were driven into vertical support columns using a "mortise and tenon" style of construction and held in place by smaller wooden dowels. A small tour of this barn and its history can be found here!

18 N Post Rd

18 N Post Rd

- 18 North Post Road - The Dutch farmhouse of this property likely dates to the 1700s. Like Ladyfaire, it was expanded throughout the centuries - including a Victorian Porch that extends across two bays of the main block and one bay of the wing. Its 1.5 story wing is the oldest, constituting the original Dutch farmhouse, with a broad overhanging fable and tall interior end chimney. Like the other two buildings, this house is in a good state of preservation, set, like the Schenck Farmstead, amid a large field still used for farming. More on the history of this house can be found here!

At least two other extant houses may also be of Dutch origin. These include 51 Lower Harrison Street, whose 1.5 story wing is possibly much older than the rest of the 1800s-era house, and 474 Cranbury Road, whose original core (now a kitchen) may have been built by eighteenth century Dutch Bergen settlers.

Many West Windsor houses seem to have distinct sections, demarcated by seams in the siding or sudden roof elevation changes. This is no accident; rather, these houses indicate that the buildings were expanded over time. In addition to the Schenck Farmstead's farmhouse and Ladyfaire, a number of extant buildings in West Windsor exhibit this characteristic. One such house is described below:

|

Early British houses were similar to their Dutch counterparts: 1.5 story buildings with gable roofs, small windows, lofts above a stony hearth, and entrances on the eaves elevation. Differences between English and Dutch buildings may only be visible in roof pitch and construction techniques; as a result, it is often hard to tell what country a building's original occupants were from. For example, the aforementioned houses at 47 Lower Harrison Street and 474 Cranbury Road may be English, not Dutch. The Schenck Farmstead's farmhouse (not the barn), likely constructed in the 1790s at 50 Southfield Road, is also ambiguous. Nevertheless, the stylistic reason was the same for both cultures - utility and economy.

As settlers began to prosper off the agrarian dominance of Central New Jersey (thus, West Windsor as well), they could afford to manifest their stylistic interests, and statuses, through their houses. Georgian style architecture - inspired by the English Renaissance and most popular between 1700 and 1800 - began to appear in new houses or additions made to older utilitarian buildings. A late style of this aesthetic - known as the Federal style (c. 1780-1820) - featured an enlarged floor plan; larger, symmetrically-placed windows; and classically-inspired architectural details around doorways, fireplace walls, and roof cornices. These edifices, at 2 to 2.5 stories, were also much larger than their predecessors, reflecting the wealth of the newly-formed, rapidly-growing United States. While only a few of these houses still exist in the township, they remain good examples of Georgian architecture:

As settlers began to prosper off the agrarian dominance of Central New Jersey (thus, West Windsor as well), they could afford to manifest their stylistic interests, and statuses, through their houses. Georgian style architecture - inspired by the English Renaissance and most popular between 1700 and 1800 - began to appear in new houses or additions made to older utilitarian buildings. A late style of this aesthetic - known as the Federal style (c. 1780-1820) - featured an enlarged floor plan; larger, symmetrically-placed windows; and classically-inspired architectural details around doorways, fireplace walls, and roof cornices. These edifices, at 2 to 2.5 stories, were also much larger than their predecessors, reflecting the wealth of the newly-formed, rapidly-growing United States. While only a few of these houses still exist in the township, they remain good examples of Georgian architecture:

|

The Greek Revival style, which saw its heyday from c. 1820-1860, soon replaced the Federal. This aesthetic celebrated classical ideals, such as order, proportion, and symmetry. It was an offshoot of the larger philosophical movement of the age: one of nationalism, virtue, and order. In the United States this sentiment especially prevailed during the "Era of Good Feelings" - a period of post-War of 1812 unity that defined the national dialogue. One house in particular stands out as an unusually good case study in this style:

|

. 51 Lower Harrison Street - This house, likely constructed c. 1850 and located in the village of Aqueduct, is one of West Windsor's best examples of Greek Revival houses. Its front entrance features a high style Greek Revival entrance with a porch of fluted Doric columns and pilasters with a full denticulated entablature. Its back entrance - pictured in the adjacent photograph and once fronting on a long-gone road that led over the Millstone River before the construction of Lake Carnegie - exhibits a similar porch. This house is similar in style to Greek Revival houses of Princeton, leading to speculation that it is a house constructed by the famed architect Charles Steadman. More information on this house and its context can be found here!

|

Soon after the Greek Revival came the Gothic Revival (c. 1830-1860), and then Italianate (c. 1840-1885). The Italianate movement was somewhat of a rebellion against the rigid forms of its predecessor, emphasizing, organic forms meant to complement their surroundings. Like Greek Revival houses, Italianate buildings borrowed from the past, but this time evoked the medieval farmhouses of the Italian countryside. One farmhouse of note still stands on Old Trenton Road and represents the transition between these two aforementioned aesthetics:

|

In the third quarter of the nineteenth century, Victorian houses (c. 1850-1910) - evoking a popular aesthetic across the Atlantic and named after one of Britain's most long-reigning queens - began to appear within the township's borders. Several of these buildings were constructed in the Victorian-Gothic style, featuring the laciness and intricacy of Victorian houses combined with the pointed arched windows of its earlier counterpart. While they still functioned as farmhouses, these buildings, like their predecessors, represented a level of prosperity needed for their construction. A notable example exists in Dutch Neck:

|

As the nineteenth century began to come to a close, and the country turned a century old, a new style, hearkening back to the nation's roots, began to become popular. Colonial Revival (c. 1880-1960) - an homage to the Georgian and Federal-style houses of the previous century - manifested itself through a myriad of houses in the township during a heyday of around 8 decades, culminating in the extensive residential developments that popped up around the township following World War II. One early example of Colonial Revival is found in Grovers Mill:

|

As the nineteenth century ceded to the twentieth, the American Four Square style began to dominate new construction. Typified by a square shaped 2 or 2.5 story house with a hipped roof and center or end bay entry and full-length porch, it became commonplace within our township. This aesthetic could be scaled well, between the small, modest houses of Berrien City and Penns Neck that were erected in the 1920s. Or, combined with Colonial Revival detailing and Palladian windows, they could be adapted to suit larger houses. One such example is found near Dutch Neck:

|

As the 1920s began to take hold, the first portents of West Windsor's suburban identity manifested, in the form of residential development in Penns Neck and Berrien City. These two neighborhoods, both built along major transportation avenues (the first near Brunswick Pike and the second next to what is now the Northeast Corridor rail line) featured a variety of styles, including American Four Square, Colonial Revival, Dutch Colonial, English Tudor, simple bungalows, and, closer to the mid-century, Cape Cod houses. Nowhere else in the township was there such a diversity of architecture, nor would there be, until after World War II. One such house - a quaint and charming English style cottage house - calls Penns Neck home and is featured below:

|

After World War II, residential construction began to take off in West Windsor, as the first of its large residential developments - about a dozen in between 1958 and 1975 - began to manifest within its borders. Featuring a variety of styles, these neighborhoods often offered pre-designed houses of a few styles per development, repeated throughout their neighborhoods with slight alterations so as to avoid a cookie-cutter appearance. One of the first such developments - located just south of High School South along Penn-Lyle Road - is Princeton Colonial Park, a prime example of post-war residential architecture:

|

Despite these post-war developments, West Windsor remained a predominantly agrarian town until around 1980. From that decade forward, a myriad of residential developments - from the wooded, stately cul-de-sacs in Windsor Ridge to the sprawling, grass lawn-defined neighborhoods of Princeton Oaks and beyond - were established throughout the township, owing, in large part, to the prosperity of the 1980s and the introduction of sewer lines into the township in the 1970s. These houses, whose developers and designers balanced aesthetic and economy, almost always borrowed from their predecessors, largely featuring homages to colonial revival and ranch-style architecture, albeit more uniformly built, and wide roads with verdant medians. One prime example is Village Grande (a 55+ active adult community), whose expansive development of 540 residences, constructed shortly after the turn of the 21st century, features only 6 models of house. Rather, the developers distinguished each house via their material choices and detailing.

Although the encroachment of suburbanization in West Windsor since the 1980s - especially along Bear Brook, Brunswick Pike, and Clarksville Road, where large condominiums housing hundreds of families have appeared since the turn of the 21st century - might lead some to think of the town as nothing but Toll Brother's developments, anything more than a cursory look would show a much more nuanced, diverse architectural scene. Each aesthetic - from the earliest Dutch farmhouses of the 1600s and 1700s to the expansive apartment complexes of the 2010s - tells a story of utility, economy and culture and represents only a part of our township's venerable architectural history. Preserving these memorials to ages past and present - whether through smart zoning and development or state/national historic register designations - is crucial to understanding, and immortalizing, the identity of West Windsor.

One path to education about many of West Windsor's architectural landmarks exists in the form of a self-led bicycle tour of over 100 of West Windsor's historic sites. Navigate to the "Historic Bike Trail" page to learn more!

One path to education about many of West Windsor's architectural landmarks exists in the form of a self-led bicycle tour of over 100 of West Windsor's historic sites. Navigate to the "Historic Bike Trail" page to learn more!