The Delaware & Raritan Canal

Overview

The American Industrial Revolution swept the United States during the 19th century, transforming the economic, political, infrastructural, and cultural landscape of the nation. West Windsor, likewise, experienced dramatic metamorphoses. Nowhere is the revolution of the township's economic dynamics more visible than in the two major transportation systems that barreled their way through the township - the interstate train system and the Delaware & Raritan Canal, both arriving in the township in the 1830s.

The American Industrial Revolution swept the United States during the 19th century, transforming the economic, political, infrastructural, and cultural landscape of the nation. West Windsor, likewise, experienced dramatic metamorphoses. Nowhere is the revolution of the township's economic dynamics more visible than in the two major transportation systems that barreled their way through the township - the interstate train system and the Delaware & Raritan Canal, both arriving in the township in the 1830s.

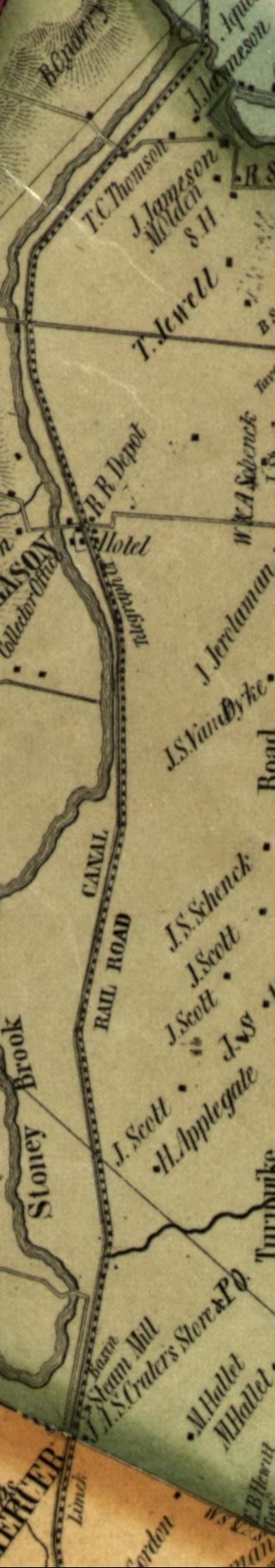

Close-up of 1849 J. W. Otley & J. Keily Map

Close-up of 1849 J. W. Otley & J. Keily Map

As early as the 1600s, New Jersey residents had considered the concept of an inland water system to connect the Delaware and Raritan rivers, and an even larger one to connect New York and Philadelphia (BR Fall 2000). The need for a swift mode of transportation for people and cargo alike, in an age when roads were still dusty, dirty, and neglected and towns had insufficient access to distant cities was a perpetual goal for many in the state.

As early as 1804, multiple plans had emerged to develop an inland waterway, (WWT&N) prompted especially by President Thomas Jefferson's call for a program of transportation initiatives that would allow easier access into the territories of the newly-acquired Louisiana Purchase. (BR Fall 2000) Support for this idea only grew stronger after the War of 1812, wherein the British blockaded the Atlantic coast, blocking passengers and cargo alike. (BR Fall 2000) Even without the difficulties of war, ocean-based travel proved so long (several weeks were needed to traverse the 200 mile trip between New York City and Philadelphia) and so treacherous (the Jersey Coast was long referred to as "The Graveyard of the Atlantic") that the thought of an alternative was a tantalizing concept. (BR Fall 2000)

Competing ideas for connecting the Delaware and Raritan, the Delaware and Hudson, and Delaware and Millstone Rivers were considered in the early 1800s, resulting in the inception of the short-lived "Assanpink Navigation Company." (WWT&N) However, after several efforts, only the Delaware and Raritan Canal scheme proved solvent. (WWT&N)

It was not until Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a United States naval officer and member of one of Princeton's most venerable families, that a successful effort was undertaken. (OPN) Around 1830, 5 years after the successful opening of the Erie Canal (BR Fall 2000), Stockton persuaded his wealthy father-in-law, James Potter, of South Carolina, to invest half a million dollars into a canal that ran between the Delaware and Raritan Rivers. (WWT&N) As a result of Potter's investment, the Delaware and Raritan Canal Commission was formed. (WWT&N) The state legislature soon forced it to incorporate as one entity with the Camden and Amboy Rail Road and Transportation Company, due to fears of a self-destructive rivalry. (WWT&N)

From Trenton to Kingston, the canal and the railroad tracks ran parallel to, and within feet of, each other. (WWT&N) Northwards of that, the two transportation systems diverged, although both grew close again in New Brunswick. (WWT&N) By the end of construction, the canal had been dug to provide uninterrupted access from Bordentown in the south to New Brunswick, its northern terminus. (WWT&N)

Although a lofty vision prompted the establishment of the canal, for the workers (who labored under Canvas White, the canal's chief engineer) the excavation of this enormous ditch was anything but ideal. (BR Fall 2000) 75 feet side, 7 feet deep, and 66 miles long, the canal required a massive effort to remove dirt, rocks, debris, and plants. (BR Fall 2000) In addition, an outbreak of cholera, spreading rapidly among the largely Irish laborers, killed thousands by the time the canal was completed (BR Fall 2000). Improvised hospitals along the canal, including around Princeton Basin, proved insufficient to contain both the disease and the panic it elicited. (OPN) West Windsor town legend claims that some are buried around Port Mercer, one of the two villages (the other being Princeton Basin) in West Windsor that developed as a result of the canal. (BR Fall 2000)

Finally, in 1834, a year after the railroad's opening the canal was completed. (BR Fall 2000) Businessmen, town residents, and politicians alike celebrated the inception of this water route, which reduced the time of travel between New York and Philadelphia to two days. (BR Fall 2000)

Although barges occasionally carried human passengers, its primary cargo was commodities. (BR Fall 2000) Agricultural products and industrial materials constituted much of the barges' loads. (BR Fall 2000) Ironically, these barges - pulled by mules that walked along "tow paths" to one side - often transported coal, which powered the train system - which, when relocated in 1865, would prove to be the nemesis of the canal companies.

As early as 1804, multiple plans had emerged to develop an inland waterway, (WWT&N) prompted especially by President Thomas Jefferson's call for a program of transportation initiatives that would allow easier access into the territories of the newly-acquired Louisiana Purchase. (BR Fall 2000) Support for this idea only grew stronger after the War of 1812, wherein the British blockaded the Atlantic coast, blocking passengers and cargo alike. (BR Fall 2000) Even without the difficulties of war, ocean-based travel proved so long (several weeks were needed to traverse the 200 mile trip between New York City and Philadelphia) and so treacherous (the Jersey Coast was long referred to as "The Graveyard of the Atlantic") that the thought of an alternative was a tantalizing concept. (BR Fall 2000)

Competing ideas for connecting the Delaware and Raritan, the Delaware and Hudson, and Delaware and Millstone Rivers were considered in the early 1800s, resulting in the inception of the short-lived "Assanpink Navigation Company." (WWT&N) However, after several efforts, only the Delaware and Raritan Canal scheme proved solvent. (WWT&N)

It was not until Commodore Robert F. Stockton, a United States naval officer and member of one of Princeton's most venerable families, that a successful effort was undertaken. (OPN) Around 1830, 5 years after the successful opening of the Erie Canal (BR Fall 2000), Stockton persuaded his wealthy father-in-law, James Potter, of South Carolina, to invest half a million dollars into a canal that ran between the Delaware and Raritan Rivers. (WWT&N) As a result of Potter's investment, the Delaware and Raritan Canal Commission was formed. (WWT&N) The state legislature soon forced it to incorporate as one entity with the Camden and Amboy Rail Road and Transportation Company, due to fears of a self-destructive rivalry. (WWT&N)

From Trenton to Kingston, the canal and the railroad tracks ran parallel to, and within feet of, each other. (WWT&N) Northwards of that, the two transportation systems diverged, although both grew close again in New Brunswick. (WWT&N) By the end of construction, the canal had been dug to provide uninterrupted access from Bordentown in the south to New Brunswick, its northern terminus. (WWT&N)

Although a lofty vision prompted the establishment of the canal, for the workers (who labored under Canvas White, the canal's chief engineer) the excavation of this enormous ditch was anything but ideal. (BR Fall 2000) 75 feet side, 7 feet deep, and 66 miles long, the canal required a massive effort to remove dirt, rocks, debris, and plants. (BR Fall 2000) In addition, an outbreak of cholera, spreading rapidly among the largely Irish laborers, killed thousands by the time the canal was completed (BR Fall 2000). Improvised hospitals along the canal, including around Princeton Basin, proved insufficient to contain both the disease and the panic it elicited. (OPN) West Windsor town legend claims that some are buried around Port Mercer, one of the two villages (the other being Princeton Basin) in West Windsor that developed as a result of the canal. (BR Fall 2000)

Finally, in 1834, a year after the railroad's opening the canal was completed. (BR Fall 2000) Businessmen, town residents, and politicians alike celebrated the inception of this water route, which reduced the time of travel between New York and Philadelphia to two days. (BR Fall 2000)

Although barges occasionally carried human passengers, its primary cargo was commodities. (BR Fall 2000) Agricultural products and industrial materials constituted much of the barges' loads. (BR Fall 2000) Ironically, these barges - pulled by mules that walked along "tow paths" to one side - often transported coal, which powered the train system - which, when relocated in 1865, would prove to be the nemesis of the canal companies.

Between 1834 and 1865, the canal and trains existed harmoniously, fueling the rise of various villages across New Jersey. (Me) In West Windsor, from south to north, the villages that were affected by the emergence of the canal were: Port Mercer, Princeton Basin, Penns Neck, and Aqueduct. As West Windsor, during the canal's heyday, was almost completely agrarian (Architectural survey), access to residents and industries in the rapidly-expanding New York City and Philadelphia proved a boon to the township.

By the 1840s, the canal began to enjoy a golden age, fueled in large part by the rapidly-growing demand for coal across the nation. (WWT&N) By 1850, coal alone accounted for eighty percent of the volume of canal shipments. (WWT&N)

Alas, the canal's heyday only lasted for three decades. By 1865, trains had grown fast enough that the curving railroad system running parellel to the canal proved insufficient and unsafe. Consequently, after much political debate, it was decided to relocate the trains a mile to the east, where a much straighter run could accommodate the more powerful trains of the latter half of the 1800s. (WWT&N) This new route, which was expanded from two tracks to four in 1893 (WWT&N) is now known as the Northeast Corridor, owned, in 2019, by Amtrak.

The relocation of the rail route proved fatal for the canal's operation. As newer, more powerful trains proved faster and able to carry larger loads, and the rail route that ran through West Windsor began to connect with an intercontinental railroad system, the canal became increasingly obsolete. By the early 1900s, the canal ceased operating as a source for carring cargo, transforming, rather, into a route on which "pleasure barges" carried wealthy passengers, looking for a leisurely vacation. (BR Fall 2000)

By the 1840s, the canal began to enjoy a golden age, fueled in large part by the rapidly-growing demand for coal across the nation. (WWT&N) By 1850, coal alone accounted for eighty percent of the volume of canal shipments. (WWT&N)

Alas, the canal's heyday only lasted for three decades. By 1865, trains had grown fast enough that the curving railroad system running parellel to the canal proved insufficient and unsafe. Consequently, after much political debate, it was decided to relocate the trains a mile to the east, where a much straighter run could accommodate the more powerful trains of the latter half of the 1800s. (WWT&N) This new route, which was expanded from two tracks to four in 1893 (WWT&N) is now known as the Northeast Corridor, owned, in 2019, by Amtrak.

The relocation of the rail route proved fatal for the canal's operation. As newer, more powerful trains proved faster and able to carry larger loads, and the rail route that ran through West Windsor began to connect with an intercontinental railroad system, the canal became increasingly obsolete. By the early 1900s, the canal ceased operating as a source for carring cargo, transforming, rather, into a route on which "pleasure barges" carried wealthy passengers, looking for a leisurely vacation. (BR Fall 2000)

However, even this usage would only last for a few decades. In 1932, the canal completely ended operation, drying up the main economic artery for much of New Jersey. (WWT&N) In West Windsor, this change hit Port Mercer and Princeton Basin the hardest. (BR Fall 2000) By the 1930s, these two hamlets - especially Port Mercer - were merely a shadow of their former selves. (BR Fall 2000)

In 1934, 100 years after the canal's opening, the state of New Jersey picked up the 999 year lease which had previously belonged to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. (WWT&N) The canal was declared a State Historic Site, existing today as a National Historic Site. (WWT&N) The Delaware & Raritan State Park operates today as a jogging and biking path running on top of the old mule tow line path, providing recreation along much of the old canal's route. (WWT&N) Within West Windsor, the old tow path runs unbroken from Port Mercer in the south to Aqueduct in the north. In addition, a kayak and canoe rental establishment has operated for decades within the old vicinity of Princeton Basin, providing further recreation.

When you can, stroll along the old towpath, taking in the sights to either side: the now slow-moving body of water that once functioned as the lifeblood of much of West Windsor to the East, and, depending on where you stand, either pastures, the Stony Brook River, or Lake Carnegie to the West. As you amble along the quiet footpath, passing by joggers, bicyclists, canoers, and kayakers alike, take the time to imagine a barge, laden with cargo, slowly drifting along. Maybe you will be able to dig up the memories of the old artery, which, for nearly a century, helped West Windsor develop alongside the rest of the nation.

In 1934, 100 years after the canal's opening, the state of New Jersey picked up the 999 year lease which had previously belonged to the Pennsylvania Railroad Company. (WWT&N) The canal was declared a State Historic Site, existing today as a National Historic Site. (WWT&N) The Delaware & Raritan State Park operates today as a jogging and biking path running on top of the old mule tow line path, providing recreation along much of the old canal's route. (WWT&N) Within West Windsor, the old tow path runs unbroken from Port Mercer in the south to Aqueduct in the north. In addition, a kayak and canoe rental establishment has operated for decades within the old vicinity of Princeton Basin, providing further recreation.

When you can, stroll along the old towpath, taking in the sights to either side: the now slow-moving body of water that once functioned as the lifeblood of much of West Windsor to the East, and, depending on where you stand, either pastures, the Stony Brook River, or Lake Carnegie to the West. As you amble along the quiet footpath, passing by joggers, bicyclists, canoers, and kayakers alike, take the time to imagine a barge, laden with cargo, slowly drifting along. Maybe you will be able to dig up the memories of the old artery, which, for nearly a century, helped West Windsor develop alongside the rest of the nation.