Slavery

A West Windsor field

A West Windsor field

New Jersey Slavery

From its first colonial settlement, the “Garden State,” whose motto alludes to its historic abundance of farmland, frequently relied on the labor of indentured servants and chattel slaves to harvest its crops. Following the importation of 11 Black slaves into the Dutch colony of New Netherland (present-day NJ, NY and CT) in 1625, slavery became an institution throughout the territory. After annexation of New Jersey by the British in 1664, the practice was encouraged by the colony’s leaders.

Many Dutch and English immigrants entered New Jersey as indentured servants, willingly or forcibly bound to work without pay, often in return for travel to the Americas or in repayment of debts. However, this convention gradually died out as conditions in England improved. Consequently, English colonists increased the importation of slaves from Africa, the West Indies, and (for a time) indigenous Americans from the Carolinas. They were bound into "chattel slavery" – a form of bondage wherein they were considered property to be bought, sold, and used. Children frequently inherited slave status from their parents and could expect to live much or all of their lives as no more than property.

West Windsor is located in what was historically East Jersey, an entity that existed when the state was split in half, from 1676-1702. As a locality located at the border between these two provinces - typified by plantation owning Quakers in West Jersey - many of whom owned slaves - and more secular and urbanized East Jersey, West Windsor inherited the culture of both halves but was subject to the laws of East Jersey. Thus, although Quaker influence found itself in early West Windsor, a 1676 provision by West Jersey that decreed "All and every persons inhabiting the said Province, shall, as far as in us lies, be free from oppression and slavery" did not extend to the land that would become West Windsor.

In 1694, East Jersey forbade slaves from carrying guns, owning property, and lodging in homes without their master's consent. The following year, the province established a separate court to try and punish slaves accused of committing felonies or murder. Even more minor transgressions were met with harshness: slaves who stole livestock would be convicted by two "justices of the peace" with no jury and publicly whipped. Their owner would be responsible for paying for both the livestock and the whipping.

Conditions only worsened with the passage of a 1704 “slave code” prohibiting any sale of property by or to slaves and free Black people, as well as whipping and jailing of any slave found more than ten miles from their home and the rejection of Christian baptism as grounds for emancipation. It was clear at this point that the 1695 law and those that followed marked a transition towards a harsher reality for slaves; one where physical punishment reigned.

New Jersey's constitution, written in 1776, provided suffrage for free African Americans and white females, alongside white males. however, an 1807 law restricted voting to only white men with to or more pounds worth of property - a provision that would last for the next 68 years.

From its first colonial settlement, the “Garden State,” whose motto alludes to its historic abundance of farmland, frequently relied on the labor of indentured servants and chattel slaves to harvest its crops. Following the importation of 11 Black slaves into the Dutch colony of New Netherland (present-day NJ, NY and CT) in 1625, slavery became an institution throughout the territory. After annexation of New Jersey by the British in 1664, the practice was encouraged by the colony’s leaders.

Many Dutch and English immigrants entered New Jersey as indentured servants, willingly or forcibly bound to work without pay, often in return for travel to the Americas or in repayment of debts. However, this convention gradually died out as conditions in England improved. Consequently, English colonists increased the importation of slaves from Africa, the West Indies, and (for a time) indigenous Americans from the Carolinas. They were bound into "chattel slavery" – a form of bondage wherein they were considered property to be bought, sold, and used. Children frequently inherited slave status from their parents and could expect to live much or all of their lives as no more than property.

West Windsor is located in what was historically East Jersey, an entity that existed when the state was split in half, from 1676-1702. As a locality located at the border between these two provinces - typified by plantation owning Quakers in West Jersey - many of whom owned slaves - and more secular and urbanized East Jersey, West Windsor inherited the culture of both halves but was subject to the laws of East Jersey. Thus, although Quaker influence found itself in early West Windsor, a 1676 provision by West Jersey that decreed "All and every persons inhabiting the said Province, shall, as far as in us lies, be free from oppression and slavery" did not extend to the land that would become West Windsor.

In 1694, East Jersey forbade slaves from carrying guns, owning property, and lodging in homes without their master's consent. The following year, the province established a separate court to try and punish slaves accused of committing felonies or murder. Even more minor transgressions were met with harshness: slaves who stole livestock would be convicted by two "justices of the peace" with no jury and publicly whipped. Their owner would be responsible for paying for both the livestock and the whipping.

Conditions only worsened with the passage of a 1704 “slave code” prohibiting any sale of property by or to slaves and free Black people, as well as whipping and jailing of any slave found more than ten miles from their home and the rejection of Christian baptism as grounds for emancipation. It was clear at this point that the 1695 law and those that followed marked a transition towards a harsher reality for slaves; one where physical punishment reigned.

New Jersey's constitution, written in 1776, provided suffrage for free African Americans and white females, alongside white males. however, an 1807 law restricted voting to only white men with to or more pounds worth of property - a provision that would last for the next 68 years.

David Lyell

David Lyell

William Penn and David Lyell: Slaveowners

Two of West Windsor’s first individual landowners – the Quaker William Penn and London goldsmith David Lyell – were slaveowners. Penn, who between 1693 and 1718 owned all land north of the Assunpink Creek and west of present-day Penn-Lyle Road, held 12 slaves on his estate, Pennsbury (north of Philadelphia). Lyell, who from 1697 to 1725 owned most of the land north of the Assunpink and east of present-day Penn-Lyle Road, held several as well. A 1716 runaway slave advertisement mentions an “Indian Man named Nim…about twenty years of age.” Another, named Tom, was executed after his participation in the New York Slave Revolt of 1712 – either by hanging or by being burned to death (sources differ). While neither Penn nor Lyell ever lived in West Windsor, it is noteworthy that the history of land ownership in our town started with these two slave owners.

Two of West Windsor’s first individual landowners – the Quaker William Penn and London goldsmith David Lyell – were slaveowners. Penn, who between 1693 and 1718 owned all land north of the Assunpink Creek and west of present-day Penn-Lyle Road, held 12 slaves on his estate, Pennsbury (north of Philadelphia). Lyell, who from 1697 to 1725 owned most of the land north of the Assunpink and east of present-day Penn-Lyle Road, held several as well. A 1716 runaway slave advertisement mentions an “Indian Man named Nim…about twenty years of age.” Another, named Tom, was executed after his participation in the New York Slave Revolt of 1712 – either by hanging or by being burned to death (sources differ). While neither Penn nor Lyell ever lived in West Windsor, it is noteworthy that the history of land ownership in our town started with these two slave owners.

Fields at the Schenck Farmstead

Fields at the Schenck Farmstead

avery at Home

Additionally, there are several documents proving ownership of at least several hundred slaves in West Windsor and its predecessor, Windsor Township.

Until the mid-1800s, our town's western border extended to Nassau Street – thus, Princeton slavery heavily overlaps with that of West Windsor.

Moreover, a 1772 census of Windsor Township lists 300 Black residents, but is is known how many are slaves. However, four censuses - from 1790, 1830, and 1840 - definitively show the number of slaves in West Windsor specifically (190, 21, 3, and 1, respectively).

Notably, the 1830 census does name John S Fisher, owner of the Schenck Farmstead, as a slaveowner. However, he owned several properties at the time so it is unknown if the Schenck Farmstead specifically housed slaves. The 1860 census seems to show Fisher as the last slaveowner in town: that year, "Diana Updike," then 76, was labeled as a "Slave Servant." Notably, she may be related to Pompey Updike, one of West Windsor's best-documented free Black residents, and a former servant for Fisher.

Following a February 15, 1804 act of the New Jersey state legislature, New Jersey began to gradually abolish slavery - albeit with glaring loopholes to appease protesting slaveowners. One such workaround was "abandonments," wherein slave children would be legally ceded to the state and bound back to their masters as "apprentices." Eight early-1800s West Windsor abandonments are known to the Historical Society and even name the children's' mothers. They also show that several of our very first township government representatives were slaveowners. See the bottom of this page to read them all.

Finally, wills mention is in the will of John Rogers (of the John Rogers House in Mercer County Park), proved in 1793. Moreover, the 1809 tax records of Dr. Israel Clark, who settled in the West Windsor hamlet of Clarksville, show ownership of at least one slave.

However, among all the known documentation of slavery in West Windsor, perhaps none is as comprehensive and revealing as the 1812 receipt of payment for a slave named Ramon:

Additionally, there are several documents proving ownership of at least several hundred slaves in West Windsor and its predecessor, Windsor Township.

Until the mid-1800s, our town's western border extended to Nassau Street – thus, Princeton slavery heavily overlaps with that of West Windsor.

Moreover, a 1772 census of Windsor Township lists 300 Black residents, but is is known how many are slaves. However, four censuses - from 1790, 1830, and 1840 - definitively show the number of slaves in West Windsor specifically (190, 21, 3, and 1, respectively).

Notably, the 1830 census does name John S Fisher, owner of the Schenck Farmstead, as a slaveowner. However, he owned several properties at the time so it is unknown if the Schenck Farmstead specifically housed slaves. The 1860 census seems to show Fisher as the last slaveowner in town: that year, "Diana Updike," then 76, was labeled as a "Slave Servant." Notably, she may be related to Pompey Updike, one of West Windsor's best-documented free Black residents, and a former servant for Fisher.

Following a February 15, 1804 act of the New Jersey state legislature, New Jersey began to gradually abolish slavery - albeit with glaring loopholes to appease protesting slaveowners. One such workaround was "abandonments," wherein slave children would be legally ceded to the state and bound back to their masters as "apprentices." Eight early-1800s West Windsor abandonments are known to the Historical Society and even name the children's' mothers. They also show that several of our very first township government representatives were slaveowners. See the bottom of this page to read them all.

Finally, wills mention is in the will of John Rogers (of the John Rogers House in Mercer County Park), proved in 1793. Moreover, the 1809 tax records of Dr. Israel Clark, who settled in the West Windsor hamlet of Clarksville, show ownership of at least one slave.

However, among all the known documentation of slavery in West Windsor, perhaps none is as comprehensive and revealing as the 1812 receipt of payment for a slave named Ramon:

Legacy

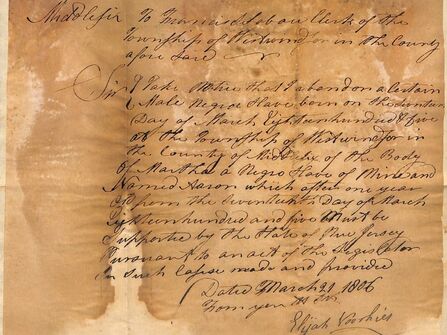

Click to read an 1806 slave abandonment.

Click to read an 1806 slave abandonment.

New Jersey was last northern state to abolish slavery. In fact, it was not until 1846 that the practice was legally outlawed. Even then, existing slaves were often simply relabeled as “apprentices” who were to serve their masters for the rest of their lives (as shown by Diana's presence on the 1860 census). Not until the end of the American Civil War and the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865 did legal slavery truly cease.

Yet, the impacts of slavery persist to this day. West Windsor, like much of the rest of the nation, played a role in this regrettable part of American history.

Yet, the impacts of slavery persist to this day. West Windsor, like much of the rest of the nation, played a role in this regrettable part of American history.

To view West Windsor's eight known slavery abandonments, play the slideshow below: