Princeton Basin

Overview

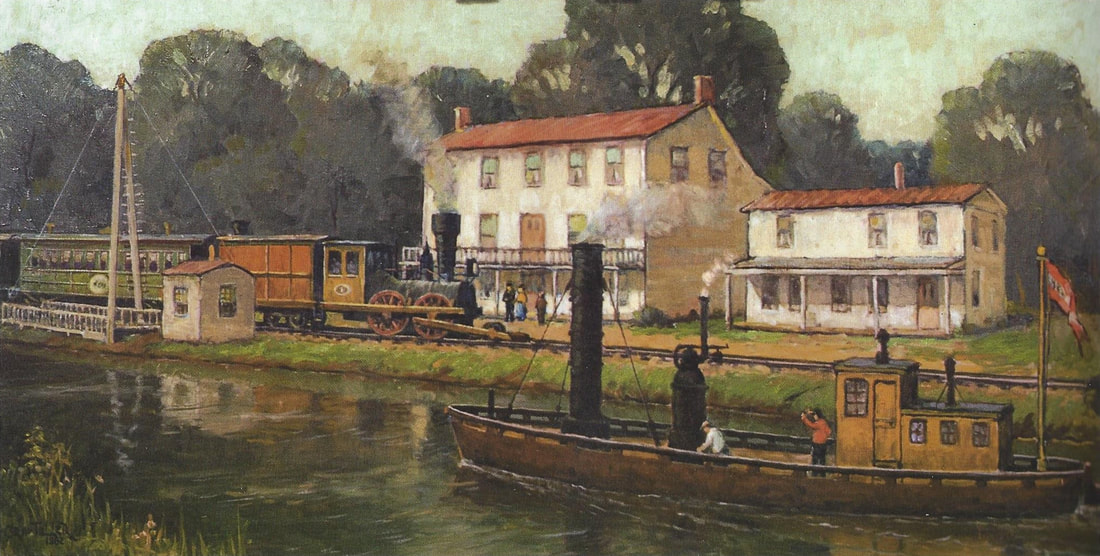

Also known as "Canal Basin," this village, much like Port Mercer, is inextricably linked to the waterway on which it resides. Soon after the Delaware and Raritan canal's opening, Princeton Basin blossomed into a bustling town straddling the border of Princeton and West Windsor. Like other canal towns, it specialized in servicing the barge passengers and their crews.¹ Unlike Port Mercer, however, Princeton Basin only experienced a short-lived age of success.

Princeton Basin is roughly organized around the intersection of the canal with Alexander Road and Alexander Street. Its northwest and southeast limits are Faculty Road and the top of the hill on the West Windsor side, just after the curve. This makes it a neighbor of Glen Acres. Historic cross-streets include Canal Road and Basin Street.

Also known as "Canal Basin," this village, much like Port Mercer, is inextricably linked to the waterway on which it resides. Soon after the Delaware and Raritan canal's opening, Princeton Basin blossomed into a bustling town straddling the border of Princeton and West Windsor. Like other canal towns, it specialized in servicing the barge passengers and their crews.¹ Unlike Port Mercer, however, Princeton Basin only experienced a short-lived age of success.

Princeton Basin is roughly organized around the intersection of the canal with Alexander Road and Alexander Street. Its northwest and southeast limits are Faculty Road and the top of the hill on the West Windsor side, just after the curve. This makes it a neighbor of Glen Acres. Historic cross-streets include Canal Road and Basin Street.

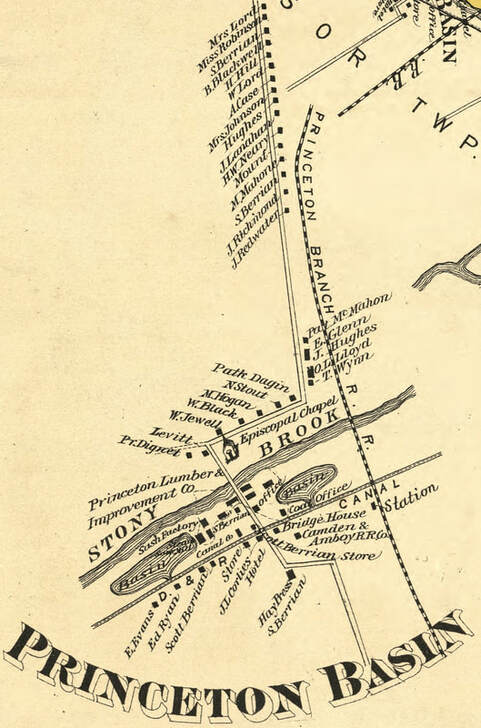

Close-up of 1875 Everts & Stuart map

Close-up of 1875 Everts & Stuart map

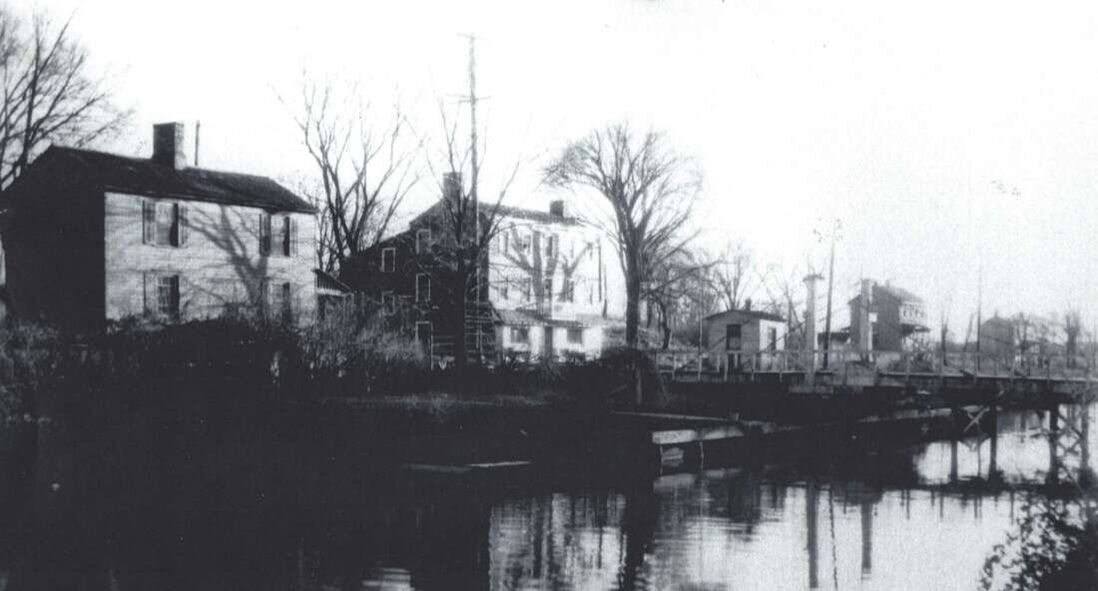

Two "turning basins" originally existed at the hamlet. These small ponds let barges moor overnight, unload freight, and turn their boats around.² Only the basin on the north side of Alexander Street still exists (now as a kayak/canoe rental establishment); the other was filled in before 1982.³ In its place is a recreational area that alludes to this history: Turning Basin Park.⁴

Among the first known buildings to be constructed in Princeton Basin was the Steamboat/Railroad Hotel.⁵ Erected between 1839 and 1849, the hotel served barge crews, mule handlers, and barge passengers, among others.⁶ Passengers and crewmen alike preferred the hotel to the cramped quarters of their barges.⁷ The hotel continued operation for roughly 150 years until it was demolished in 1992.⁸

One of the first commercial enterprises along the canal was a general store run by Scott Berrien, father of Alexander Lawrence Berrien, eponymous creator of Berrien City.⁹ His store, demolished in the 1930s, was one of the busiest establishments in the area, providing a myriad of goods for townsmen, canal workers, and passengers alike.¹⁰ It also became a focal point for the town, serving as a centralized meeting place.¹¹ Berrien continued to serve the village, including as a freight collector and owned of a lumber company, until his death at the age of 92.¹²

The completion of the West Windsor stretch of the Camden and Amboy railroad in 1839 proved a boon to the hamlet, until its relocation in 1863.¹³ Offering direct Philadelphia-New York service, it provided access to a rapidly-growing regional marketplace.¹⁴

Among the first known buildings to be constructed in Princeton Basin was the Steamboat/Railroad Hotel.⁵ Erected between 1839 and 1849, the hotel served barge crews, mule handlers, and barge passengers, among others.⁶ Passengers and crewmen alike preferred the hotel to the cramped quarters of their barges.⁷ The hotel continued operation for roughly 150 years until it was demolished in 1992.⁸

One of the first commercial enterprises along the canal was a general store run by Scott Berrien, father of Alexander Lawrence Berrien, eponymous creator of Berrien City.⁹ His store, demolished in the 1930s, was one of the busiest establishments in the area, providing a myriad of goods for townsmen, canal workers, and passengers alike.¹⁰ It also became a focal point for the town, serving as a centralized meeting place.¹¹ Berrien continued to serve the village, including as a freight collector and owned of a lumber company, until his death at the age of 92.¹²

The completion of the West Windsor stretch of the Camden and Amboy railroad in 1839 proved a boon to the hamlet, until its relocation in 1863.¹³ Offering direct Philadelphia-New York service, it provided access to a rapidly-growing regional marketplace.¹⁴

Princeton Basin's businesses were diverse. Between 1837 and 1866, Aaron L. and S.C. Green sold doors, sashes, and blinds.¹⁵ In 1863, J.B. Wycoff managed a warehouse housing hay, wood, and produce.¹⁶ Three years later the New Jersey Iron Clad Roofing, Paint and Mastic Company was formed.¹⁷ One of its members, John W. Fielder, also owned the Princeton Lumber and Improvement Company.¹⁸

Other vendors included Johnson and McKean (who offered produce in exchange for potatoes), A.B. Tomilson (lumber/coal), William T. Anderson (groceries, dry goods, and Peruvian guano for use as fertilizer), and, notoriously, Billy Lynch.¹⁹ Lynch's "Bottle House" was known as a seedy establishment even to local college students and canal workers.²⁰ As a result, the police were among the most frequent visitors.²¹

Joseph Henderson and Widow Skillman operated "hackey coaches" (4-wheeled carriages pulled by 2 horses that could carry up to 6 passengers), providing transportation between the Princeton railroad depot and Princeton Basin.²² Riders were asked to write their names on various locations in Princeton to be picked up there.²³

Other vendors included Johnson and McKean (who offered produce in exchange for potatoes), A.B. Tomilson (lumber/coal), William T. Anderson (groceries, dry goods, and Peruvian guano for use as fertilizer), and, notoriously, Billy Lynch.¹⁹ Lynch's "Bottle House" was known as a seedy establishment even to local college students and canal workers.²⁰ As a result, the police were among the most frequent visitors.²¹

Joseph Henderson and Widow Skillman operated "hackey coaches" (4-wheeled carriages pulled by 2 horses that could carry up to 6 passengers), providing transportation between the Princeton railroad depot and Princeton Basin.²² Riders were asked to write their names on various locations in Princeton to be picked up there.²³

The height of Princeton Basin was around 1875. At the time, the community contained dozens of buildings, including a hotel, a general store, a hay press, an Episcopal chapel, a lumber yard, a railroad station, a bridge tender's house, two turning basins, a sash factory, and over 3 dozen residences.²⁴ Like Port Mercer, Princeton Basin saw over 1400 barges a week carrying 3 million tons of cargo.²⁵

In the 1870s and 1880s, John L. Corlies ran the hotel.²⁶ He was notable for his potential involvement in the death of Solomon Krauskopf.²⁷ In 1872, the body of Solomon Krauskopf was discovered with a pistol bar through his heart.²⁸ Missing from his person was around $170 in cash, a watch and chain, and a revolver.²⁹ Corlies was suspected of the murder.³⁰ In 1882, the Asbury Park Shore Press published an open letter from Corlies, in which he both disputed any involvement in Krauskopf's death, and denied his own death, as several papers had recently published Corlies' obituary!³¹

Besides Scott Berrien, other bridge tenders were: an "Oliver" who went blind due to exposure in the blizzard of 1888 and "Old John" Coan, father of Bill Coan, who drove mules for Captain Hogarty of the barge "Francis Kelley."³² The basin's last bridge-tender was Jean Weitzman who lived on Alexander Road.³³

Another notable figure was "Bob" Murphy. As the canal's paymaster, Murphy was often exposed to dangerous people unwilling to pay. Legend say that when he was threatened by a gang of dockyard thugs, he successfully fought them off, throwing several of them into the canal. ³⁴

The only 1800s-era industry to survive into the 1900s was a bottling plant managed by Martin Vandenberg from 1908 to 1911.³⁵

In the 1870s and 1880s, John L. Corlies ran the hotel.²⁶ He was notable for his potential involvement in the death of Solomon Krauskopf.²⁷ In 1872, the body of Solomon Krauskopf was discovered with a pistol bar through his heart.²⁸ Missing from his person was around $170 in cash, a watch and chain, and a revolver.²⁹ Corlies was suspected of the murder.³⁰ In 1882, the Asbury Park Shore Press published an open letter from Corlies, in which he both disputed any involvement in Krauskopf's death, and denied his own death, as several papers had recently published Corlies' obituary!³¹

Besides Scott Berrien, other bridge tenders were: an "Oliver" who went blind due to exposure in the blizzard of 1888 and "Old John" Coan, father of Bill Coan, who drove mules for Captain Hogarty of the barge "Francis Kelley."³² The basin's last bridge-tender was Jean Weitzman who lived on Alexander Road.³³

Another notable figure was "Bob" Murphy. As the canal's paymaster, Murphy was often exposed to dangerous people unwilling to pay. Legend say that when he was threatened by a gang of dockyard thugs, he successfully fought them off, throwing several of them into the canal. ³⁴

The only 1800s-era industry to survive into the 1900s was a bottling plant managed by Martin Vandenberg from 1908 to 1911.³⁵

The abandonment of the canal by the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1932 and the canal's closing in 1934 surely marked the death knell for Princeton Basin, so entrenched in the canal's operation.³⁶ A mere 5 years later, in 1939, Princeton Basin had long passed its heyday. In this year, the Federal Writer's Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) produced "Old Princeton's Neighbor's."³⁷ In this publication, Princeton Basin was described as having 18 residences and a trucking business and junk yard owned by A. Shure.³⁸

One interesting note in "Old Princeton's Neighbors" is its observation of a series of willow trees along the canal and on Princeton University's campus. Legend says that they were grown from twigs originally found on the island of St. Helena close to Napoleon Bonaparte's grave and transported to Princeton by William Theodore Van Doren, an alumn of the New Brunswick Theological Seminary.³⁹ It is unknown if any of these trees still stand.

In 1982, the Delaware & Raritan Canal commission prepared a "Historic Structures Survey."⁴⁰ By this year, almost none of the canal's original buildings remained. Only a handful of houses still stood next to an algae and weed-choked turning basin and canal:

"Gone are the house and office of the superintendent of the canal, the house and station for the bridgetender, and the Camden and Amboy Railroad tracks, railroad depot and agent's house," the survey lamented. "Gone too are all signs of the shops, mills and factories that once crowded around the intersection of the canal, and the railroad and Alexander Road." ⁴¹

The survey went on to note that the oldest residences at the time were likely the Commodor Stockton building and M. Vorhees house on the Princeton bank of the canal, as well as the Scott Berrien and Ed Ryan houses on the West Windsor side.⁴²

One interesting note in "Old Princeton's Neighbors" is its observation of a series of willow trees along the canal and on Princeton University's campus. Legend says that they were grown from twigs originally found on the island of St. Helena close to Napoleon Bonaparte's grave and transported to Princeton by William Theodore Van Doren, an alumn of the New Brunswick Theological Seminary.³⁹ It is unknown if any of these trees still stand.

In 1982, the Delaware & Raritan Canal commission prepared a "Historic Structures Survey."⁴⁰ By this year, almost none of the canal's original buildings remained. Only a handful of houses still stood next to an algae and weed-choked turning basin and canal:

"Gone are the house and office of the superintendent of the canal, the house and station for the bridgetender, and the Camden and Amboy Railroad tracks, railroad depot and agent's house," the survey lamented. "Gone too are all signs of the shops, mills and factories that once crowded around the intersection of the canal, and the railroad and Alexander Road." ⁴¹

The survey went on to note that the oldest residences at the time were likely the Commodor Stockton building and M. Vorhees house on the Princeton bank of the canal, as well as the Scott Berrien and Ed Ryan houses on the West Windsor side.⁴²

"Lottie B." barge on canal near Steamboat Hotel. Photo courtesy of Historical Society of Princeton.

"Lottie B." barge on canal near Steamboat Hotel. Photo courtesy of Historical Society of Princeton.

With the demolishing of the Steamboat/Railroad Hotel in 1992, there are only two buildings left in West Windsor (as of 2019) that hearken back to the golden age of the canal: 8-10 Canal Road (Scott Berrien's house) and 14 Canal Road (Ed Ryan's house).⁴³ On the Princeton Side are 6 residences along Basin Street, the turning basin (now in operation as a kayak/canoe launching area), Turning Basin Park, and the heavily-modified bridge.⁴⁴

And, of course, the Delaware & Raritan Canal. In 1974, the establishment of the D&R Canal Park turned Princeton Basin into a recreational area, inviting jogging, walking, biking, canoeing, and kayaking along the canal.⁴⁵ It is along these routes that one can experience both the tranquility of nature and the echoes of a more prosperous age for the Basin.

And, of course, the Delaware & Raritan Canal. In 1974, the establishment of the D&R Canal Park turned Princeton Basin into a recreational area, inviting jogging, walking, biking, canoeing, and kayaking along the canal.⁴⁵ It is along these routes that one can experience both the tranquility of nature and the echoes of a more prosperous age for the Basin.

Entrance to the remaining turning basin

Entrance to the remaining turning basin

Turning Basin (1830s)

This basin was built around 1934 to accommodate boats that needed to offload and turn around⁴⁶ Boats entered by a narrow bottleneck, over which a small drawbridge for mules was laid.⁴⁷ By 1982, the southern basins had been filled in.⁴⁸ However, the one pictured still functions for watercraft - albeit acting as a launching dock for canoes and kayaks in 2019.⁴⁹

This basin was built around 1934 to accommodate boats that needed to offload and turn around⁴⁶ Boats entered by a narrow bottleneck, over which a small drawbridge for mules was laid.⁴⁷ By 1982, the southern basins had been filled in.⁴⁸ However, the one pictured still functions for watercraft - albeit acting as a launching dock for canoes and kayaks in 2019.⁴⁹

Courtesy of Historical Society of Princeton.

Courtesy of Historical Society of Princeton.

Former Swivel Bridge (1830s)

Much like the bridge in Port Mercer, this construct swiveled on a pivot, functioning similarly to a drawbridge, albeit with horizontal displacement, not vertical.⁵⁰ The bridge tender would be responsible for this rotation.⁵¹ Early photographs of the bridge distinguish it from today's static construct, rebuilt in 2020 to replace a wooden bridge erected in 1948.

Much like the bridge in Port Mercer, this construct swiveled on a pivot, functioning similarly to a drawbridge, albeit with horizontal displacement, not vertical.⁵⁰ The bridge tender would be responsible for this rotation.⁵¹ Early photographs of the bridge distinguish it from today's static construct, rebuilt in 2020 to replace a wooden bridge erected in 1948.

From "Princeton Architecture: A Pictorial History of Town and Campus"

by Constance M. Greiff, Mary W. Gibbons, and Elizabeth G.C. Menzies

From "Princeton Architecture: A Pictorial History of Town and Campus"

by Constance M. Greiff, Mary W. Gibbons, and Elizabeth G.C. Menzies

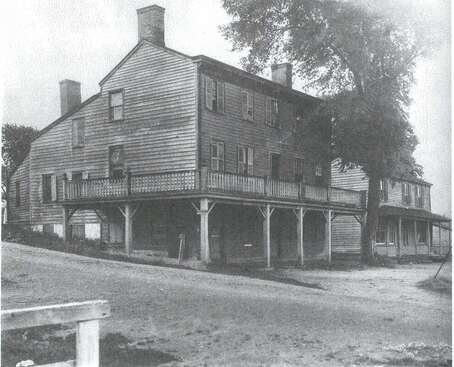

2 Canal Road: Steamboat/Railroad Hotel

(c. 1839-1849)

Among the first buildings to be constructed in Princeton Basin was the Steamboat/Railroad Hotel.⁵² Erected between 1839 and 1849, the hotel served barge crews, mule handlers, and barge passengers, among others.⁵³ Sheds to house mules were located behind the hotel.⁵⁴ Passengers and crewmen alike preferred the hotel to the cramped quarters of their barges.⁵⁵

The hotel also served as a supplementary shop to Scott Berrien's general store.⁵⁶ What could not be purchased from Berrien was often found in this establishment.⁵⁷

Prior to the 1860s, a "Mr. Skillman" managed the hotel successfully. John L. Corlies operated the hotel in the 1870s and 1880s.⁵⁸ It was during his ownership of the hotel that Solomon Krauskopf, a Princeton Jeweler, was murdered, whereupon Corlies was accused. The murder was never solved.

After Corlies were Pat Degnan were a "Mr. Carol," and John J. O'Kane (or Kane).⁵⁹ In the 1930s, an attempt to convert the hotel into a tavern was shot down.⁶⁰ The then-owner, Alexander Rodwaller, used the building as a residence.⁶¹

The last owner of the hotel was Mrs. Della Jenkins, a former school teacher, known for walking all the way to the township offices each quarter to pay her township taxes in cash.⁶² Upon her death, it was concluded that the hotel was too dilapidated to be saved.⁶³ Consequently, roughly 150 years after its construction, the hotel was demolished in 1992.⁶⁴ A residence was built in its place in 1995.⁶⁵

(c. 1839-1849)

Among the first buildings to be constructed in Princeton Basin was the Steamboat/Railroad Hotel.⁵² Erected between 1839 and 1849, the hotel served barge crews, mule handlers, and barge passengers, among others.⁵³ Sheds to house mules were located behind the hotel.⁵⁴ Passengers and crewmen alike preferred the hotel to the cramped quarters of their barges.⁵⁵

The hotel also served as a supplementary shop to Scott Berrien's general store.⁵⁶ What could not be purchased from Berrien was often found in this establishment.⁵⁷

Prior to the 1860s, a "Mr. Skillman" managed the hotel successfully. John L. Corlies operated the hotel in the 1870s and 1880s.⁵⁸ It was during his ownership of the hotel that Solomon Krauskopf, a Princeton Jeweler, was murdered, whereupon Corlies was accused. The murder was never solved.

After Corlies were Pat Degnan were a "Mr. Carol," and John J. O'Kane (or Kane).⁵⁹ In the 1930s, an attempt to convert the hotel into a tavern was shot down.⁶⁰ The then-owner, Alexander Rodwaller, used the building as a residence.⁶¹

The last owner of the hotel was Mrs. Della Jenkins, a former school teacher, known for walking all the way to the township offices each quarter to pay her township taxes in cash.⁶² Upon her death, it was concluded that the hotel was too dilapidated to be saved.⁶³ Consequently, roughly 150 years after its construction, the hotel was demolished in 1992.⁶⁴ A residence was built in its place in 1995.⁶⁵

Scott Berrien's General Store (mid-1800s)

This building, demolished in the 1930s, was among the most successful of the town's enterprises, and one of its earliest establishment.⁶⁶ It served a variety of goods, from coal to agricultural products to wood to masonry supplies.⁶⁷ Also sold were a variety of blankets, clothing, candles, tobacco, and tow lines for barges.⁶⁸ As a result of the establishment's success, it became a meeting place for the community.⁶⁹ In the 1860s, the store also housed a sash and blind factory run by J.W. Fielder and Sons, as well as the laundry and dyeing establishment of a French emigrant, M. Gerneau, of Princeton.⁷⁰

Unfortunately, a fire destroyed the hay press that Berrien used as a freight collector, and Berrien's business never recovered.⁷¹ He sold the land to the Improvement Association (Messrs. Fielder, Beekman, & Co.).⁷²

Berrien was a veritable jack-of-all-trades. In addition to the aforemenioned enterprises, Berrien not only owned the Reardon Lumber Company at 200 Alexander Road; he also served as the village's freight collector.⁷³ As freight was transported through the village, it had to be weighed to verify that the transport invoice was correct.⁷⁴ Fees associated with weight and type of cargo were then charged.⁷⁵

He passed away at the age of 92, long a stalwart figure of the village.⁷⁶

This building, demolished in the 1930s, was among the most successful of the town's enterprises, and one of its earliest establishment.⁶⁶ It served a variety of goods, from coal to agricultural products to wood to masonry supplies.⁶⁷ Also sold were a variety of blankets, clothing, candles, tobacco, and tow lines for barges.⁶⁸ As a result of the establishment's success, it became a meeting place for the community.⁶⁹ In the 1860s, the store also housed a sash and blind factory run by J.W. Fielder and Sons, as well as the laundry and dyeing establishment of a French emigrant, M. Gerneau, of Princeton.⁷⁰

Unfortunately, a fire destroyed the hay press that Berrien used as a freight collector, and Berrien's business never recovered.⁷¹ He sold the land to the Improvement Association (Messrs. Fielder, Beekman, & Co.).⁷²

Berrien was a veritable jack-of-all-trades. In addition to the aforemenioned enterprises, Berrien not only owned the Reardon Lumber Company at 200 Alexander Road; he also served as the village's freight collector.⁷³ As freight was transported through the village, it had to be weighed to verify that the transport invoice was correct.⁷⁴ Fees associated with weight and type of cargo were then charged.⁷⁵

He passed away at the age of 92, long a stalwart figure of the village.⁷⁶

Princeton Trinity Church Mission (c. 1850)

Around 1850, a small chapel of Princeton's Trinity Church was constructed.⁷⁷ It served as both house of worship and school.⁷⁸ Rachel Stevens, a Princeton resident, devoted long hours to the church.⁷⁹ James Potter, also of Princeton, established the school.⁸⁰ In 1934, the building, a simple-frame structure on a stone foundation, was taken apart and relocated to Camp Nejech on the Metedeconk River in Ocean County.⁸¹ It was rebuilt there and has continued to serve as a recreation hall and choir chapel.

Around 1850, a small chapel of Princeton's Trinity Church was constructed.⁷⁷ It served as both house of worship and school.⁷⁸ Rachel Stevens, a Princeton resident, devoted long hours to the church.⁷⁹ James Potter, also of Princeton, established the school.⁸⁰ In 1934, the building, a simple-frame structure on a stone foundation, was taken apart and relocated to Camp Nejech on the Metedeconk River in Ocean County.⁸¹ It was rebuilt there and has continued to serve as a recreation hall and choir chapel.

8-10 Canal Road (c. 1850): 8-10 Canal Road

Scott Berrien may have lived in this house; one of the oldest in the hamlet.⁸² It is also one of only 2 that still exist on the West Windsor side of the canal.⁸³ To its left stood the hotel, and across the canal was Berrien's general store.

Scott Berrien may have lived in this house; one of the oldest in the hamlet.⁸² It is also one of only 2 that still exist on the West Windsor side of the canal.⁸³ To its left stood the hotel, and across the canal was Berrien's general store.

14 Canal Road (c. 1850): Ed Ryan House

This house, located to the southwest of Scott Berrien's house, is the only other extant residence in Princeton Basin from the 1800s.⁸⁴ It is also one of the hamlet's oldest structures. According to the 1875 map, it also abutted the entrance to the southern turning basin.⁸⁵

This house, located to the southwest of Scott Berrien's house, is the only other extant residence in Princeton Basin from the 1800s.⁸⁴ It is also one of the hamlet's oldest structures. According to the 1875 map, it also abutted the entrance to the southern turning basin.⁸⁵

Princeton Basin Train Station & Canal Bridge (1860s)

At the time that the Dinkey line from West Windsor to Princeton was constructed in 1863, the canal had already been in operation for over three decades.⁸⁶ A bridge thus needed to span the canal, but it also could not prevent barges from passing through. The solution was a bridge that turned on a central hub, built on a cylindrical stone foundation.⁸⁷ This mechanism can still be seen today under the railroad tracks that are still in use. The only thing that has changed is that the bridge no longer turns for nonexistent canal traffic.⁸⁸

Also constructed in the mid-1800s was a station at Princeton Basin, south of the tracks.⁸⁹ It has long since disappeared but can be seen on the maps of Princeton Basin near the top of this page.

At the time that the Dinkey line from West Windsor to Princeton was constructed in 1863, the canal had already been in operation for over three decades.⁸⁶ A bridge thus needed to span the canal, but it also could not prevent barges from passing through. The solution was a bridge that turned on a central hub, built on a cylindrical stone foundation.⁸⁷ This mechanism can still be seen today under the railroad tracks that are still in use. The only thing that has changed is that the bridge no longer turns for nonexistent canal traffic.⁸⁸

Also constructed in the mid-1800s was a station at Princeton Basin, south of the tracks.⁸⁹ It has long since disappeared but can be seen on the maps of Princeton Basin near the top of this page.

Play the slideshow below to explore more of historic Princeton Basin!