A Revolutionary March

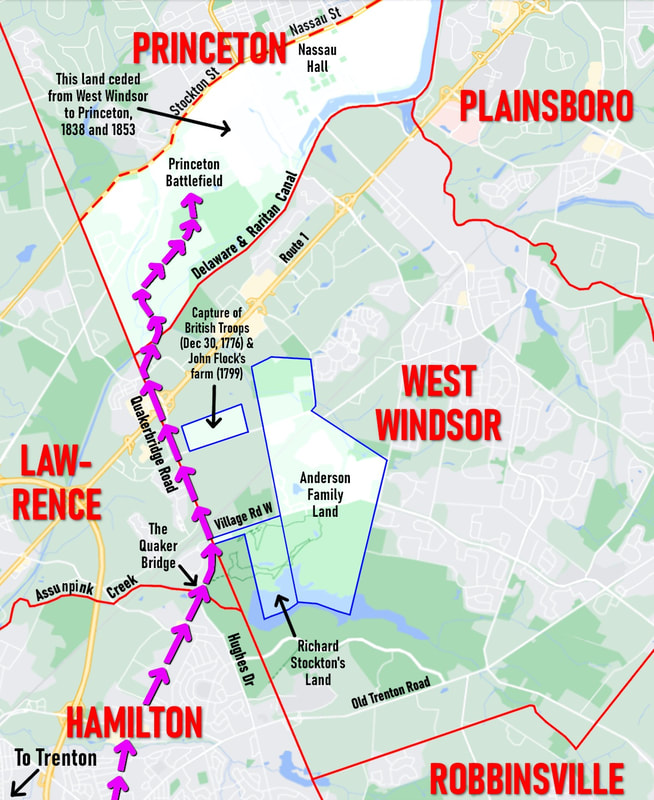

It is January 3, 1777 amid the Revolutionary War. George Washington has just won two victories at Trenton, but cannot repel superior British forces for long. However, British troops recently captured in present-day West Windsor have revealed that nearby Princeton is poorly fortified. Thus begins a march toward that village - through West Windsor, and to victory.

Historical Overview

|

The period between December 25, 1776, and January 3, 1777, is commonly known as the "Ten Crucial Days." This week and a half was critical to United States' history, where three triumphs - the first and second Battles of Trenton (December 26, and January 2, respectively) as well as the Battle of Princeton (January 3) - helped General George Washington snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Previously, his demoralized soldiers had suffered repeated defeats throughout 1776, and with their contracts expiring at years'-end, many intended to resign. This may have very well lost Washington the entire American Revolution. However, those three victories in the Ten Crucial Days helped sway a substantial number of soldiers to renew their contracts. They also further convinced additional recruits to join in the spring, positioned Washington to eventually drive the British out of New Jersey, and laid the groundwork for the patriots to rally broader support for their Revolution.[1]

On January 2, nearly a week after Washington's surprise victory at the Battle of Trenton, British General Charles Cornwallis and about 8,000 troops marched from Princeton to reclaim Trenton. He left about 1,200 troops stationed at Princeton under command of Lieutenant Colonel Mawhood. That day, in the Second Battle of Trenton, 7,000 British and Hessian soldiers fought Washington's army in a fierce artillery duel on either side of the Assunpink Creek. The American soldiers managed to hold off their enemy until the evening, when both armies retreated to regroup. Believing he, with his superior forces, had his foe trapped, Cornwallis waited until morning to renew the attack.[2] However, Washington had other plans. Three days prior (December 30), a small American scouting party had captured a dozen British soldiers in present-day West Windsor and brought them to Trenton to be interrogated. The intel they gave - corroborated the next day by a letter sent from American Colonel John Cadwalader in Crosswicks - revealed British troop size and position in Princeton and also alerted Washington that British General Lord Charles Cornwallis intended to march with thousands of reinforcements to recapture Trenton.[3],[4],[5] Not only did this help Washington prepare for the Second Battle of Trenton; it also alerted his council of war that Princeton was now poorly fortified. Thus, as night fell on January 2, they decided to escape Cornwallis' superior forces by slipping their army out of Trenton and capturing Princeton instead.[6] |

|

That night, while a small contingent stayed in the city, lighting fires and making noise to fool Cornwallis into believing the Americans were still encamped, the majority of Washington's army left the city that cold winter night, heading north. Great care was made to slip out silently, and to mask the scheme, even to Washington's own soldiers. Their route largely followed Quakerbridge Road - West Windsor's border with Lawrence Township. In fact, they marched over the old "Quaker Bridge" itself, built to span the Assunpink Creek and connect Quaker communities in Princeton and Crosswicks.[7]

The army was led by three local Hunterdon County Regiment militiamen: Patrick Lamb, Elias Phillips, and Ezekiel Anderson.[8] Ezekiel's family owned hundreds of acres near Quakerbridge Road in present-day West Windsor.[9] So, too, did other influential Revolutionaries (see adjacent map):

|

|

Onward the soldiers trudged for thirteen miles, through cold and wind, in the dead of night. However, the sun soon literally - and metaphorically - rose, when the Americans engaged with, and triumphed over, the British at the Battle of Princeton on January 3, 1777. Sadly, one of Washington's counterparts - Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, after whom Mercer County and the historic West Windsor village of Port Mercer were named - was mortally wounded in this battle. However, despite this personal loss, the broader victory gave Washington his third triumph in those Ten Crucial Days. Moreover, by the time Cornwallis realized he had been tricked and made it to Princeton, it was too late; Washington had already left the village and marched toward Morristown.[15]

In 1777, Princeton - not yet an independent town of its own - was part of the larger Windsor Township Even after Windsor Township split in 1797 into East Windsor and West Windsor, West Windsor Township encompassed all land in Princeton southeast of Nassau Street - including Thomas Clarke's farm and Nassau Hall, the sites at which the Battle of Princeton primarily took place.[16] In fact, it was not until 1838 that West Windsor Township lost Nassau Hall upon Princeton's formal creation as a township,[17] and not until 1853 that it lost the Princeton Battlefield when Princeton annexed all land northwest of the Delaware and Raritan Canal.[18] In 1914, the Sons of the Revolution installed twelve granite obelisks between Trenton and Princeton, marking Washington's January 3, 1777 march.[19] One overlaps the border of West Windsor and Lawrence Townships, in the Quakerbridge Road median about 200 feet northwest of that road's intersection with Province Line Road.[20] These obelisks remain memorials to this transformative juncture in American history in which West Windsor played a critical role. |

Bibliography

- Kidder, William Larry. Ten Crucial Days: Washington’s Vision for Victory Unfolds. Brentwood, Tennessee: Knox Press, 2020

- Ibid.

- Peters, Thomas. “A Scrap of ‘Troop’ History.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 15, no. 2, 1891. Contains transcription of notes written by Thomas Peters, Revolutionary War soldier, written in 1818, in his copy of the "By-Laws of the First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry," itself printed in 1815. These notes were donated to the Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography by a "Mrs. Roberdeau Buchanan," Peters' granddaughter.

- Wilkinson, James. Memoirs of my own times. Vol. 1. 3 vols. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Printed by Abraham Small, 1816.

- Reed, William B. Life and correspondence of Joseph Reed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1847.

- Kidder, William Larry. Ten Crucial Days: Washington’s Vision for Victory Unfolds. Brentwood, Tennessee: Knox Press, 2020

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Anderson, Johannes, Gordon, John. “Indenture.” Windsor, 1747. Located in the New Jersey state Archives, East Jersey Deeds Volume AN Page 402.

- “Application for Membership - The New Jersey Society of the National Society Sons of the American Revolution.” Hamilton Township, New Jersey, July 13, 1965. Mervin Tindall Flock's application for membership. Application mentions that Flock served with Burlington Co. militia. Application was approved and registered by Registrar General on July 13, 1965. Application references the Flock family bible, Hamilton Square Graveyard, and the Service of E. Farnsworth.

- "The Story of a Trip of Quaker Bridge Patriots." Trenton Evening Times. May 4, 1902.

- Flock, John, Woolley, James. “Indenture.” Windsor, 1799. Located in the New Jersey state Archives, Middlesex County Deed Book 6 Page 250.

- https://www.morven.org/about

- Brooks, James, Stockton, Richard. “Indenture.” Windsor, 1765. Located in the New Jersey state Archives, East Jersey Deeds Volume E3 Page 307.

- Kidder, William Larry. Ten Crucial Days: Washington’s Vision for Victory Unfolds. Brentwood, Tennessee: Knox Press, 2020

- An Act for Dividing the Township of Windsor in the County of Middlesex into Two Separate Townships. New Jersey State Archives, 1797. February 9, 1797. This split Windsor Township into West Windsor and East Windsor.

- "Supplement to An Act to Erect Parts of the Counties of Hunterdon, Burlington, and Middlesex into a New County, to Be Called the County of Mercer.,” 1838.

- “An Act to Annex a Part of the Township of West Windsor, in the County of Mercer, to the Township of Princeton, in the Said County.,” March 9, 1853.

- “To Mark Washington’s Route from Trenton to Princeton.” Sunday Times-Advertiser. March 8, 1914.

- Personal observations of the author of this article (Paul Ligeti)