(Press the play button below to hear the full broadcast)

In 1938, a science-fiction radio play called "War of the Worlds" thrust the historic West Windsor community of Grovers Mill into the national spotlight as the site of a "Martian invasion." National hysteria reputedly ensued as fact morphed into fiction. The broadcast is a potent example of the power of media and disinformation. Explore the story below!

Historical Overview

|

Back in 1938, West Windsor Township was a small, little-known agricultural municipality of just 2,000 people. Farmland stretched across virtually all of its landscape and its nights were quiet, typically interrupted only by a breeze rustling through fields of crops, the chirp of a cricket, or the hoot of an owl. However, on the evening of "Mischief Night" (Oct. 30), 1938, a rising star named Orson Welles forever thrust the tiny West Windsor neighborhood of Grovers Mill into national infamy.

Welles, then 23 years old, and his associate, John Houseman, were co-founders of Mercury Theater on the Air - a radio troupe that reenacted famous works of literature.[1] Radio was accessible to even those impoverished by the Great Depression. Be it economic turmoil, the Lindburg Baby kidnapping of 1932, the Hindenburg explosion of 1936, or rising fascism in Europe, airwaves were often filled with unsettling reports that unsettled the nation. However, there were also more uplifting items, such as comedy specials, sports, and the voice of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in his "fireside chats" reaching into millions of living rooms to reassure the nation.[2] |

|

It was in this environment that Mercury Theater reinterpreted English author H. G. Wells' 1898 science fiction novel, The War of the Worlds, about an alien invasion of Earth. However, whereas the book was set in England, the radio play was Americanized. In the days leading up to the broadcast, writer Howard Koch closed his eyes and dropped the point of a pencil on a New Jersey road map at random. It landed on Grovers Mill - a place he didn't know but whose homespun name and proximity to the Princeton observatory he liked.[3]

At the time, science fiction was largely considered a child's genre and the broadcast was to compete with more popular programs. Thus, it was rewritten to better enthrall its audience. The Mercury Theater formatted it as if it were a real news broadcast interrupting an otherwise scheduled musical act. Sound effects were inserted and real-life places and institutions were referenced - such as fake narration from the Secretary of the Interior (voiced by Kenneth Delmar, who made the Secretary sound like the deeply-trusted President Roosevelt).[4],[5] |

|

At 8PM Eastern Standard Time, radio listeners tuned into the Mercury Theater. After a brief monologue by Welles on intelligent alien life, he set the story in late October 1939. Then, the fictitious "Ramón Raquello and his Orchestra" began playing a slow tango. However, the music was soon cut off by an announcement that Princeton astronomers had observed explosions on Mars. The music then returned, but over the next several minutes, it was repeatedly interrupted - first by an interview with a fictitious "Professor Pierson" of Princeton, then by reports that a meteor had landed in Grovers Mill, later by an interview with Grovers Mill resident "farmer Wilmuth," and, finally, by the emergence of Martians out of the impact crater, surrounded by curious onlookers.[6],[7] It was here that the fictional reporter Carl Phillips captured the start of the invasion:

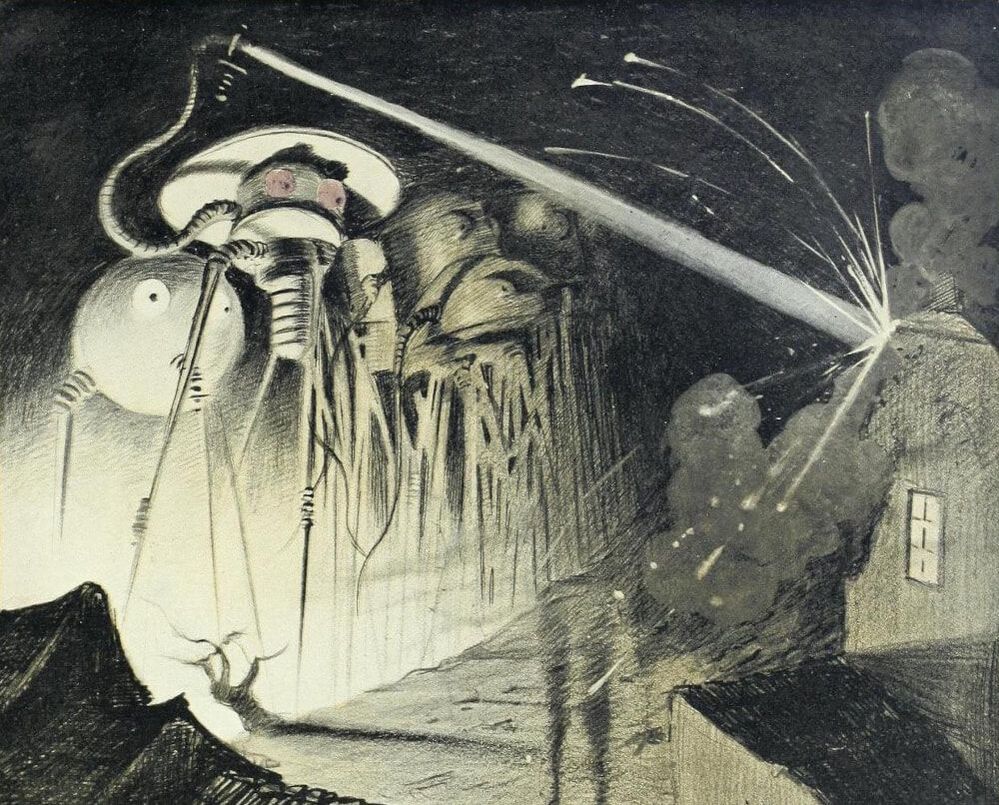

A humped shape is rising out of the pit. I can make out a small beam of light against a mirror. What’s that? There’s a jet of flame springing from the mirror, and it leaps right at the advancing men. It strikes them head on! Good Lord, they’re turning into flame! [SCREAMS AND UNEARTHLY SHRIEKS] Now the whole field’s caught fire. [EXPLOSION] The woods . . . the barns . . . the gas tanks of automobiles . . . it’s spreading everywhere. It’s coming this way. About twenty yards to my right . . . [MICROPHONE ABRUPTLY CUTS][8] After a period of unbearable silence, the broadcast resumed. Over most of the next hour - interrupted once, about forty minutes in, by a disclaimer that this was a radio play - more "news bulletins" portrayed the planet under attack by Martians. Hordes of monstrous tripods roamed the landscape, wreaking destruction wherever they went. Millions of refugees fled cities as poison gas and death rays destroyed armies and infrastructure. In the end, it was only germs - to which the invaders had no immunity - that defeated the aliens. The play ended as it began, with a monologue, as well as a disclaimer that this was, again, a work of fiction.[9]

|

|

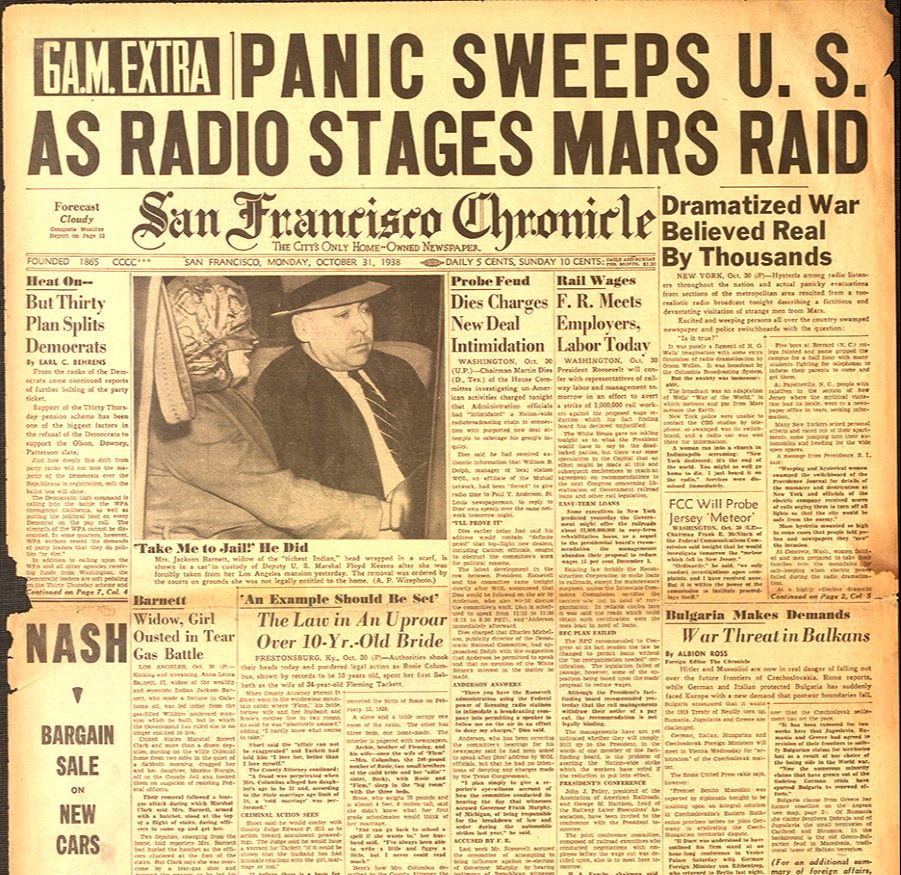

Welles and the rest of the Mercury Theater didn't expect the masses to be fooled by such silly subject matter. However, as the live broadcast was airing, police attempted to enter the studio and by the time the play ended, phones were ringing off the hook. The next morning, newspapers across the country plastered their front pages with reports about how "hysteria" had swept the nation, with listeners believing the Martian invasion to be true. Thousands of people supposedly fled their homes, took their own lives, and formed militias to fight back against the extraterrestrials. As the tales go, the nation was practically at war against a nonexistent threat.[10],[11]

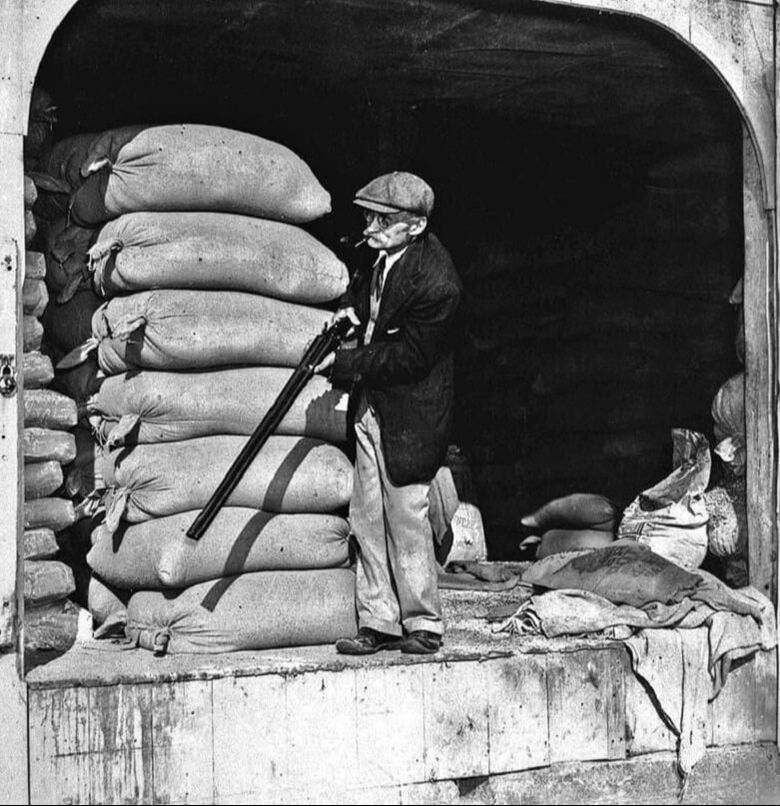

This same panic is reputed to have struck sleepy Grovers Mill, with residents piling into their cars, attempting to flee. Ted Perrine and his family are said to have stopped for gas but in their panic forgot to remove the hose and drove away, ripping off the nozzle.[12] A drunken farmer (or several, depending on the narrator) even supposedly shot at the water tower behind the millwright's house, believing it to be an alien tripod.[13] These tales have lasted for decades - but how much of it is true? Is this tale of mass hysteria, itself, yet another fiction? |

|

Contemporary research in fact reveals that the actual extent of the reaction to the broadcast was dramatically exaggerated. Rather than mass hysteria sweeping the nation, there were isolated "pockets" of panic where the reaction was more severe - typically in New Jersey and New York. In Grovers Mill itself, the majority of residents were unperturbed because they could look outside and see that nothing was amiss. It is indeed true that cars crowded the Grovers Mill area (and a few local families perhaps did flee). However, much traffic actually streamed toward Grovers Mill, from both reporters and inquisitive visitors who had heard a meteor had crashed into the community, often without associating it with aliens at all.[14] Telephone lines were indeed jammed - and in fact, Trenton's City Manager sent a letter to the FCC, decrying that "two thousand phone calls were received in about two hours, all communication lines were paralyzed."[15] However, much (but not all) of these calls were from people attempting to verify the broadcast's authenticity and quickly realizing that it was a non-story.[16]

Moreover, most didn't even hear the broadcast at all; one survey says that two percent of radio-owners listened to it.[17] And of those who did, a large portion didn't even realize it was about aliens. Many only heard words like "poison gas," "meteor," and "martial law" and instead feared a natural disaster or human-caused war (especially with a rising fascist threat across the Atlantic). There are very few verifiable reports of people fleeing their homes; rather, the minority that was afraid largely clung to their radios and called their loved ones until they realized it was fiction. Yet more, who weren't even listening to the radio, only vaguely heard something was amiss from their panicked neighbors without knowing the subject matter was about aliens.[18] |

|

So where did the tales of hysteria originate? Much of the reaction was exaggerated by newspapers - who not only had a financial incentive to increase viewership by embellishing the panic's scope and severity, but who themselves received a disproportionate share of the phone calls the night of October 30, by readers attempting to verify the broadcast's authenticity. This tricked newspaper editors into thinking this was a larger story than it really was.[19]

And what of the farmer drunkenly shooting at the water tower? Howard Koch himself visited the community in 1969, and he questioned if it happened.[20] Furthermore, so did members of the Bruno family,[21] who lived in the millwright's house in the 1960s-80s.[22],[23] The legend likely comes from a photo of William Dock - a retired mill worker who humored reporters by posing for them after the broadcast (see the nearby image).[24] His likeness seems to have been twisted over time into hordes of shotgun-toting farmers. Dock, in fact, became so synonymous with the broadcast that he was featured in a DC comic book (Secret Origins, Vol. 2 No. 5, August 1986) battling a faux "Martian" invader![25] |

|

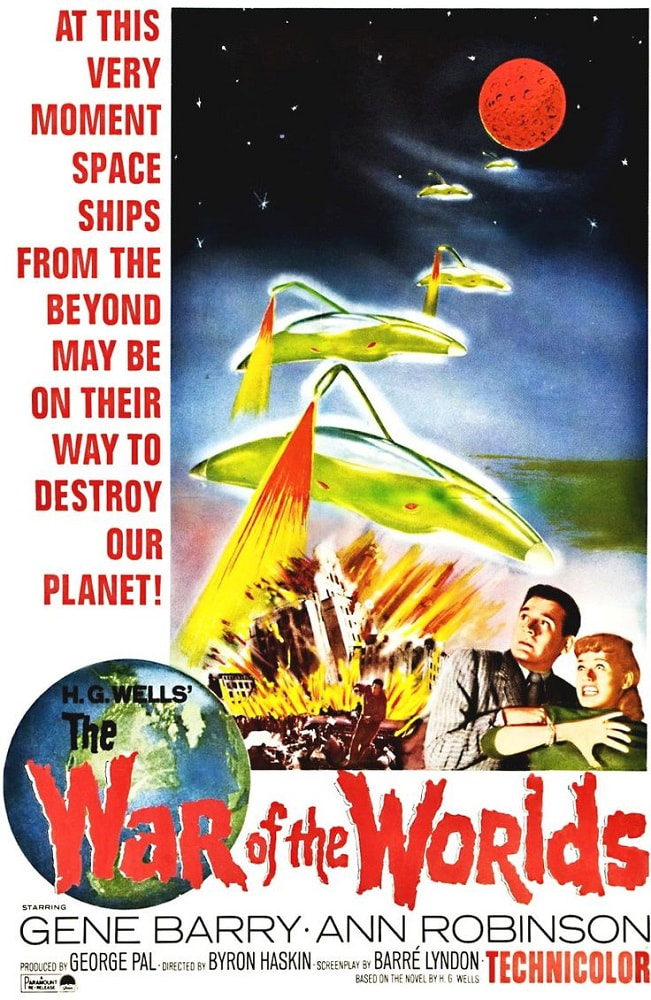

In the decades since, the radio play has taken on a "larger than life" identity. A movie was released in 1953 reinterpreting the novel[26] and another one followed in 2005.[27] Numerous documentaries have been produced and books have been written about the broadcast that thrust Orson Welles into instant A-list stardom (he would direct one of the most famous films of all time, "Citizen Kane," only two years later).[28]

In contrast, for many decades, West Windsor locals generally paid little attention to the broadcast's legacy. To them, the ongoing recognition was "much ado about nothing" and even an annoyance to some.[29] However, as the decades passed, this attitude changed. In 1988, the Township celebrated the broadcast's 50th anniversary over several days, including a parade, 10-K run, art show, panel discussions, and even the installation of a bronze plaque in Van Nest Park (sculpted by Thomas Jay Warren), whose dedication 86-year-old Koch attended.[30],[31] In the years since, other local initiatives have sprung up. At the time of this writing (2023), the Grovers Mill Coffee House provides pastries and drinks to locals and travelers alike. Near the West Windsor Arts Center in Berrien City, a 12-foot-tall sculpture called "Scoutship" depicts a Martian tripod. And of course, the Historical Society of West Windsor exhibits artifacts and recounts stories related to the broadcast and has even been interviewed by various news sources, including the nationally-syndicated CBS Saturday Morning - see below. With all this in mind, bring on the next invasion! |

Watch our War of the Worlds interview with CBS Saturday Morning (Oct 28, 2023):

Bibliography

- “MERCURY THEATRE ON THE AIR.” Omeka RSS. Accessed October 11, 2023. https://orsonwelles.indiana.edu/collections/show/8.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Koch, Howard. The Panic Broadcast. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, and Company, 1970.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Koch, Howard. The Panic Broadcast. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, and Company, 1970.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Koch, Howard. The Panic Broadcast. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, and Company, 1970.

- Orson, Welles, Koch Howard, and Houseman John. “The War of the Worlds.” Episode. Mercury Theater On the Air 1, no. 17. New York, New York: CBS, October 30, 1938.

- Ibid.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Koch, Howard. The Panic Broadcast. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, and Company, 1970.

- "Another Terror Attack, but Not by Humans." New York Times. June 29, 2005.

- Scott, Marvin. “The War of the Worlds Anniversary: The Night That Terrified America.” Parade, October 1978. Retrieved via the following URL: https://pix11.com/news/local-news/new-jersey/the-war-of-the-worlds-anniversary-the-night-that-terrified-america/

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Morton, Paul. Letter to Federal Communications Commission. “Complaint - WABC Broadcast.” Trenton, New Jersey: Town Hall, October 31, 1938.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- “Survey of Radio Listeners,” October 30, 1938. Survey of 5,000 radio listeners by C. E. Hooper company.

- Schwartz, A. Brad. Broadcast hysteria: Orson Welles’s war of the worlds and the art of fake news. New York: Hill and Wang, A division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

- Ibid.

- Koch, Howard. The Panic Broadcast. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, and Company, 1970.

- Ligeti, Paul T. I., and Bruno, Scott. Interview with Scott Bruno. Personal, 2021. Note: the Bruno family lived in 175 Cranbury Road from the 1960s-80s.

- Bruno, A. Spencer, Bruno, Elise, Grovers Mill Co. Mercer County Clerk’s Office, 1966. Found in Mercer County Clerk’s Office Records Room – Mercer County Deed Book 1753 Page 47.

- Bruno, A. Spencer, Bruno, Elise, Shope-Mok, Catherine R., Shope-Mok, Lewis S. Mercer County Clerk’s Office, 1987. Found in Mercer County Clerk’s Office Records Room – Mercer County Deed Book 2401 Page 33.

- William Dock at Grovers Mill. Photograph. West Windsor Township, New Jersey, October 31, 1938. West Windsor History Museum.

- Thomas, Roy, Gene Colan, and Mike Gustovich. Secret Origins 2, no. 5, August 1986. Published by DC Comics

- Pal, George. The War of the Worlds. Film. United States: Paramount Pictures, 1953.

- Kennedy, Kathleen, Colin Wilson, Josh Friedman, and David Koepp. War of the worlds. Film. United States: Paramount Pictures, 2005.

- Citizen Kane: Ultimate Collector’s edition. Film. United States: RKO Radio Pictures, 1941.

- "Steven Spielberg Aside, Mars Has Attacked Before." New York Times. June 19, 2005.

- Bradbury, Ray, and Ben Bova. The Complete War of the Worlds: Mars’ Invasion of Earth from H.G. Wells to Orson Welles. Edited by Brian Holmsten and Alex Lubertozzi. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2001.

- “West Windsor Township Meeting Minutes, 1797-2012.,” n.d. Original Township Committee meeting minute database located in the Municipal Center.