The Armstrong Murders

Amzi Armstrong

Amzi Armstrong

Overview

Although there is much in West Windsor of which to be proud, our township has not eluded tragedy. Today, the Historical Society of West Windsor explores one of the very few homicides to have every taken place in our community - the Armstrong Murders of 1910.

Note: This tale is not only depressing but also racially charged - in the crime, its context, and in the newspapers that reported the events. Please be aware that there are racial slurs in some of the newspaper articles on this page.

Murder

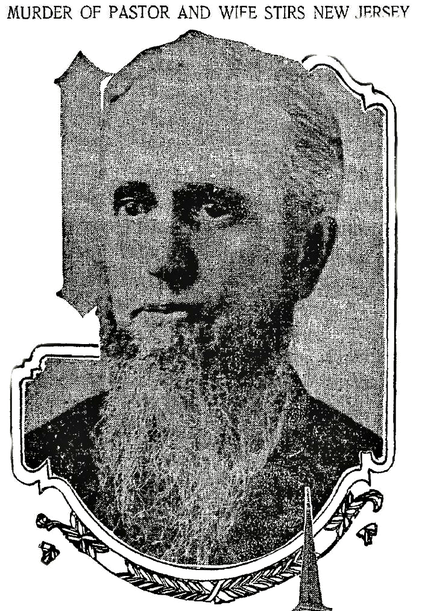

Throughout its existence, the Dutch Neck Presbyterian Church has witnessed a variety of clergy members, but none as memorable as the Reverend Amzi L. Armstrong, Pastor from 1857-1900. However, for all his years of service, his life was unfortunately overshadowed by the grim nature of his death.

Around 8 or 9 PM on November 23, 1910, gunshots pierced the silence of Thanksgiving Eve. Around 1 AM, a distraught 33-year-old John Sears – “adopted” by the Armstrongs as a baby – woke up neighbors, saying he had come home

Although there is much in West Windsor of which to be proud, our township has not eluded tragedy. Today, the Historical Society of West Windsor explores one of the very few homicides to have every taken place in our community - the Armstrong Murders of 1910.

Note: This tale is not only depressing but also racially charged - in the crime, its context, and in the newspapers that reported the events. Please be aware that there are racial slurs in some of the newspaper articles on this page.

Murder

Throughout its existence, the Dutch Neck Presbyterian Church has witnessed a variety of clergy members, but none as memorable as the Reverend Amzi L. Armstrong, Pastor from 1857-1900. However, for all his years of service, his life was unfortunately overshadowed by the grim nature of his death.

Around 8 or 9 PM on November 23, 1910, gunshots pierced the silence of Thanksgiving Eve. Around 1 AM, a distraught 33-year-old John Sears – “adopted” by the Armstrongs as a baby – woke up neighbors, saying he had come home

Rachel Sears.

Rachel Sears.

from New Brunswick to find the 83-year-old Amzi and his 45-year-old second wife, Ann Rue, robbed and shot to death. His biological mother, Rachel Sears - who had lived with them as a servant since John was 3 weeks old - was hiding upstairs at the time of the murder.

George Dennison, a neighbor with one of the few phones in the community, called the police. Acting Sergeant Fitzpatrick notified the authorities around 2:00 AM and Prosecutor Crossley, Assistant Prosecutor Piper, Detective Kirkham, and Coroners Boers and Grove arrived at the crime scene shortly thereafter. Following an off-site autopsy, county Physician Scammel concluded that both Armstrongs had been shot with a 12-guage gun.

Investigation

John’s friend, Rudolph Nordhaus of New Brunswick, also arrived that morning. He had been invited to spend Thanksgiving with Sears at the Armstrong home. However, upon departure from a Trenton-New Brunswick “Fast Line” car (see our post from June 20) he was intercepted by Prosecutor Crossley and thoroughly interrogated. Although he was eventually released, his testimony proved instrumental in uncovering the murderer.

It grew rapidly apparent that there were holes in John’s alibi. He had claimed that he was visiting Nordhaus in New Brunswick for an appointment, but Nordhaus told the police he never showed up. Shortly before the murder, neighbors witnessed John borrowing a shotgun like the one used in the killings. Moreover, Sears had, reputedly, previously told some friends that he thought some day he would be one of the heirs of the property of the Rues, parents of Mrs. Armstrong. The Armstrongs themselves were childless – thus, many believed this to be a major motivation for the murder.

George Dennison, a neighbor with one of the few phones in the community, called the police. Acting Sergeant Fitzpatrick notified the authorities around 2:00 AM and Prosecutor Crossley, Assistant Prosecutor Piper, Detective Kirkham, and Coroners Boers and Grove arrived at the crime scene shortly thereafter. Following an off-site autopsy, county Physician Scammel concluded that both Armstrongs had been shot with a 12-guage gun.

Investigation

John’s friend, Rudolph Nordhaus of New Brunswick, also arrived that morning. He had been invited to spend Thanksgiving with Sears at the Armstrong home. However, upon departure from a Trenton-New Brunswick “Fast Line” car (see our post from June 20) he was intercepted by Prosecutor Crossley and thoroughly interrogated. Although he was eventually released, his testimony proved instrumental in uncovering the murderer.

It grew rapidly apparent that there were holes in John’s alibi. He had claimed that he was visiting Nordhaus in New Brunswick for an appointment, but Nordhaus told the police he never showed up. Shortly before the murder, neighbors witnessed John borrowing a shotgun like the one used in the killings. Moreover, Sears had, reputedly, previously told some friends that he thought some day he would be one of the heirs of the property of the Rues, parents of Mrs. Armstrong. The Armstrongs themselves were childless – thus, many believed this to be a major motivation for the murder.

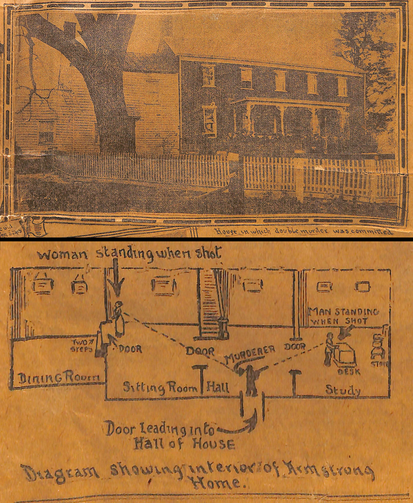

Photograph and diagram of house in 1910.

Photograph and diagram of house in 1910.

Abuse & Revenge

However, Sears – who was mixed race (Rachel was Black and his father, who left when he was born, was white) - asserted additional motives: that of racism, abuse, and revenge. According to testimony by John published in The Freehold Transcript (Dec. 2), on the day of the murder, he implored Amzi to let him go to New Brunswick to talk to Nordhaus about a lucrative chicken-raising business idea, but was denied. Armstrong insisted he go to the local mill for some feed instead. An argument ensued and Armstrong struck Sears on the head with his cane. Mrs. Armstrong then threatened to kick him out of the house if he did not comply. Later that evening, according to Sears’ confession, (also published in the New York Times on Nov. 27) when he asked for a dollar to attend a gathering in New Brunswick by a military company to which he belonged, “she called me a n*****. And that made me mad, for I am not a n*****. I am a white man.” Sears himself cited this as a primary motivation for the killing.

Shortly afterwards, Sears went to the mill, concluding to kill the couple by the time he returned. As he walked back into the house, the New York Times reported, he “walked by Mrs. Armstrong, and shot her husband to death. Then he turned to flee and found Mrs. Armstrong about to hurl a large glass vase at him. With that he leveled the weapon at her and fired and she fell dying to the floor.”

Although Sears attempted an alibi by traveling to New Brunswick to meet Nordhaus, he could not find him, so he left word for Nordhaus to come to Dutch Neck the following day and went back home. His mother, thrust into a horrendous dilemma over which she had little control, agreed to tell the police that it was a robbery gone bad.

However, Sears – who was mixed race (Rachel was Black and his father, who left when he was born, was white) - asserted additional motives: that of racism, abuse, and revenge. According to testimony by John published in The Freehold Transcript (Dec. 2), on the day of the murder, he implored Amzi to let him go to New Brunswick to talk to Nordhaus about a lucrative chicken-raising business idea, but was denied. Armstrong insisted he go to the local mill for some feed instead. An argument ensued and Armstrong struck Sears on the head with his cane. Mrs. Armstrong then threatened to kick him out of the house if he did not comply. Later that evening, according to Sears’ confession, (also published in the New York Times on Nov. 27) when he asked for a dollar to attend a gathering in New Brunswick by a military company to which he belonged, “she called me a n*****. And that made me mad, for I am not a n*****. I am a white man.” Sears himself cited this as a primary motivation for the killing.

Shortly afterwards, Sears went to the mill, concluding to kill the couple by the time he returned. As he walked back into the house, the New York Times reported, he “walked by Mrs. Armstrong, and shot her husband to death. Then he turned to flee and found Mrs. Armstrong about to hurl a large glass vase at him. With that he leveled the weapon at her and fired and she fell dying to the floor.”

Although Sears attempted an alibi by traveling to New Brunswick to meet Nordhaus, he could not find him, so he left word for Nordhaus to come to Dutch Neck the following day and went back home. His mother, thrust into a horrendous dilemma over which she had little control, agreed to tell the police that it was a robbery gone bad.

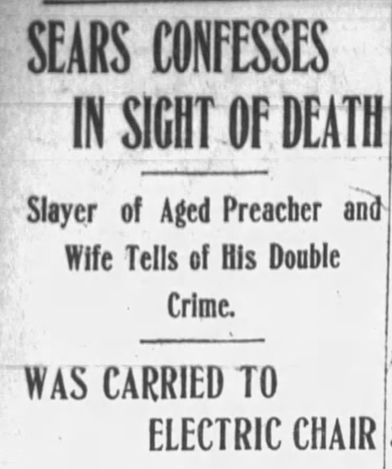

Caption from the March 16, 1911 edition of the Camden-Post Telegram.

Caption from the March 16, 1911 edition of the Camden-Post Telegram.

Trial & Execution

John Sears was charged with murdering the Armstrongs shortly thereafter. As the investigation and subsequent trial unfolded, the story was reported not just in Mercer County but also across the country - as far as Washington State and in hundreds of independent newspapers from November to March. This was largely due to the intimate and inflammatory details of the family and murder in an otherwise sleepy farming community. With almost no exception, newspapers deliberately highlighted Sears’ race and Armstrong’s popularity in the community.

Sears confessed to the murder after several days of interrogation. He led the police on a walkthrough of the house, explaining how he committed the crime. On December 3, a “Coroner’s jury” indicted Sears of murder. When a subsequent trial began on January 30, the New Brunswick Times reported that “the (Mercer County Courthouse) could not accommodate half the crowd…and about five hundred persons were unable to gain admission.” Prosecutor Crossley asked for a first-degree murder conviction and following a hasty trial (the verdict was returned in less than 1.5 hours), on February 1, Sears was sentenced to death.

John Sears died in the electric chair on March 15, 1911 – the first person in Mercer County to be killed this way. His death followed his mother’s passing on February 19, from heart failure and heartbreak. To this day, the house in which this tragedy unfolded still stands within the Crown Pointe development off Old Trenton Road, a centuries-old memorial to one of West Windsor’s most depressing episodes.

John Sears was charged with murdering the Armstrongs shortly thereafter. As the investigation and subsequent trial unfolded, the story was reported not just in Mercer County but also across the country - as far as Washington State and in hundreds of independent newspapers from November to March. This was largely due to the intimate and inflammatory details of the family and murder in an otherwise sleepy farming community. With almost no exception, newspapers deliberately highlighted Sears’ race and Armstrong’s popularity in the community.

Sears confessed to the murder after several days of interrogation. He led the police on a walkthrough of the house, explaining how he committed the crime. On December 3, a “Coroner’s jury” indicted Sears of murder. When a subsequent trial began on January 30, the New Brunswick Times reported that “the (Mercer County Courthouse) could not accommodate half the crowd…and about five hundred persons were unable to gain admission.” Prosecutor Crossley asked for a first-degree murder conviction and following a hasty trial (the verdict was returned in less than 1.5 hours), on February 1, Sears was sentenced to death.

John Sears died in the electric chair on March 15, 1911 – the first person in Mercer County to be killed this way. His death followed his mother’s passing on February 19, from heart failure and heartbreak. To this day, the house in which this tragedy unfolded still stands within the Crown Pointe development off Old Trenton Road, a centuries-old memorial to one of West Windsor’s most depressing episodes.